Posts on: politics

Part III: Proletarian Love

Truth is not an unveiling which destroys the secret, but the revelation which does it justice.

—Walter Benjamin

At the risk of seeming ridiculous, let me say that the true revolutionary is guided by a great feeling of love. It is impossible to think of a genuine revolutionary lacking this quality.

—Che Guevara

If the entire problem of the Paradox was precisely that of fetishism, of romanticising things, then we can see immediately that this whole time, without realising it, we have been meditating on one central issue: love. If there is one thing that the Paradox demands of us, it is to practice a true and universal love; indeed, it is precisely this kind of love that proletarian politics aspires to.

As the Che quote above acknowledges, this does, initially, sound vapid, meaningless, and trite. However, in that any meaningful social revolution presupposes some kind of egalitarian fraternity of people who come together under the banner of a shared Cause, it is impossible to deny that the revolution implies revolutionary love, or at the very least some sort of revolutionary belonging. Let us call this revolutionary love “proletarian love”, and the subject that practices this love the proletarian or the comrade. In light of the discussions of the Paradox in the previous two parts, here we round off this essay by thinking through the following question: what is this proletarian love? Which perhaps is equivalent to asking that one vexed, eternal question: what is true love?

*

I don’t pretend to have any kind of definitive answer to this question, and I am not about to present a “Theory of True Proletarian Love” (which sounds like just about the least loving thing I could do right now). Nonetheless, I do think it’s possible to creep closer to some kind of answer by framing the question negatively, and asking instead: what is proletarian love not?

First off, proletarian love is not a love “for” the working class. This is simply the problem of fetishism all over again, the reduction of the working class to a particular series of fixed attributes and symbols. Instead, our aim is a kind of love which loves the working class insofar as they are stand-ins for all of humanity; in other words, a universal love. In Part II, we described this universality as concerned with a kind of “brush with the void”: the universal expressed itself through the working class via their encounter with the unnameable void at the heart of everything, for example when they attempted to start a community project solely through the resources they had available to them, and without any funding, recognition or validation from the State. Although the working class could be said to have a “privileged” relation to this void (also known as “epistemic privilege” by standpoint theorists and Mark Fisher), in principle anyone can—and indeed more often than not do at some point—have this kind of “brush with the void”. It is in regards to this encounter with the negative that our proletarian love is universal, as will be explored more shortly.

At the same time, however, it is important to clarify that this proletarian love is not universal in the sense that, say, hippies understand it, as a kind of uniform declaration of “peace and love”, or a chilled-out pacifism. This makes a mistake that we also identified in the previous part: the mistaking of universality for identity or uniformity. To practice universal love is not to show the same undifferentiated love to every particular thing we encounter. This, clearly, is not “love” in any meaningful sense: if you claim to equally love both the slave and the slave-trader who whips them, each of them accordingly know your love to be absolutely meaningless. It seems inescapable, then, but to argue that all love is inherently engaged in the activity of taking sides: love fixates on singular things and elevates them above the rest; it orders and prioritises.

And so we find ourselves at an impasse: our universal proletarian love must on the one hand a) aspire to universality, and yet on the other hand also be b) ruthlessly partisan; it must seek a grace and forgiveness that can extend to all, and serve the interests of the whole of humanity, and yet at the same time vehemently draw its dividing lines, say “no” to the bourgeois powers that be, and stand up against oppression and exploitation. So proletarian love in some way loves all humanity; but in another way, it detests the bourgeoisie, and it spits on the careerist demagogues that so frequently lead the people astray. Is this not a contradiction? How can one claim to love all humanity and yet basically hate one small, albeit powerful, section of it? Does this not defeat our entire project?

No, and for this reason: the particular and the universal are not separate “things”, categories or labels but rather, by necessity, dialectically related. In other words we reach the universal through the particular, and not in spite of it. Indeed any concept of “universal” without the corresponding concept of “particular” is quite literally empty, something akin to the hippie’s “universal love” referred to above.

So to reiterate: proletarian love is something that strives to speak for (all) the People—in other words, the Common Folk—but does so through engaging in divisive, antagonistic political struggle. It is a kind of commitment to the Common Folk, the “true”, anonymous People lurking underneath the false images of the People that claim to be it (national flags, emblems, monarchs, and so on).

Let’s try and make this a bit more concrete; how would one feasibly practice proletarian love? How does one reach the universal “through” the particular? Our starting point is to remember that though we seek to act as (=on behalf of) the People, we never encounter people as the People, that anonymous, faceless public: we only ever interact with the particular people that we come across in our particular lives. So we begin with those often mundane, everyday moments that we are all so familiar with: a friend is complaining about their relationship, a colleague is moaning about their work, a family member is struggling to get the healthcare they need, and so on. Now, suppose we take the second example here: you are on your lunch break at work and your colleague, who you are quite friendly with, is having difficulties with their manager. Out of a fraternal love, you resolve to help them; after all, it could have been you with the difficulties, and in that situation the friend/colleague would have done the same for you. The colleague figures it’s just a small personal dispute, and they need your help preparing for a meeting with the manager in private, which you oblige to. However, after a little thought, it becomes clear that this situation could not just have affected you two, but almost the entire workplace, and indeed almost the entirety of the public, in principle. This changes things: it means helping your colleague prepare for a backroom meeting with their manager where they can privately resolve their differences no longer feels like a fair path to take. Instead, you and the colleague resolve to, rather than treat this issue as a private one between two individuals, open the issue up: to the other workers, to the public — in other words, to the Common Folk. You call a union meeting and get the workers talking to one another; you write up a press release about your actions and send it to the local newspaper. In short, you transform a private issue into a political issue; you turn a “for us” into a “for all”; you elevate fraternal love (the love between friends) into proletarian love (the anonymous love that exists between the People, as strangers, akin to “the love of one’s neighbour” in the Christian tradition).

It is this act of opening up that is the act of proletarian love par excellence, because it is precisely this that allows a particular struggle to connect with a whole host of others and begin to metonymically “stand in” for them all, and therefore begin to truly express the universal (= the People = the Common Folk). Had the friend kept their workplace complaint to themselves, this universality that the particular issue was “nested” within would never have been unravelled, and we would never had had the People chanting on the streets; we would never even believe such a thing possible.

Now, this feeling (or lack thereof) of possibility is precisely why we characterise this entire process as “love”: because it involves faith, commitment. For as any activist knows, the People do not exist in actuality yet: they have to be built. (This is precisely what distinguishes the Left from the Right: the Right assumes the People always-already exist in an identifiable form.) The People, the Common Folk, are an abstract, ideal, a priori and (Zizek would say) “impossible-real” universality that has no actual existence right now, in that we do not live in a wonderful fraternity of equals who treat each other with total selflessness and kindness. This, however, does not stop the concept from being useful, and indeed necessary for political action1. It is, after all, literally impossible to think any kind of genuine politics without some kind of a priori notion of the People baked in from the start: all political struggle is grounded on the assumption that, at some level, the People genuinely are all equal, and all equally free, and that this a priori state has been corrupted by some injustice that has introduced inequality and hierarchy into the system. Of course, we know that this is basically a fiction, a mythology, but at the same time we cannot do without it: the alternative is to assume that instead of being fundamentally equal, humanity is fundamentally unequal, and this, naturally, simply ends up in strictly hierarchical, caste-like societies which could be said to lack any meaningful definition of “politics”, because everyone simply is forced to stay in their place rather than make claims on some shared resource. Instead of this arrangement, the proletarian dares to make that leap of faith that characterises all love2: they dare to act as if that a priori ideal—the People, the Common Folk—already exists, they dare to speak to, and as, the People, even though this subject does not exist yet, and is always, perennially, to-come. And finally, crucially, it is ironically only by acting as if this object really exists that we eventually actually make it exist. It is only by daring to believe that “the people will be free” that we eventually assemble the chanting mass on the streets that seems to genuinely sound the birth-pangs of a genuinely free People. The process here is always the same: the leap of faith retroactively constructs the ground it leaped from; the proposition back-engineers its own proof. (In CCRU-inspired theory circles, this process of fictions becoming real is known as “hyperstition”. In common parlance? “Fake it ‘til you make it”.)

-

In the same way, the circle, as a purely abstract mathematical object, is not found as such in Nature; we find many patterns and objects that tend towards perfect circularity (e.g. a soap bubble), but if we were to examine these closely enough, they would not of course be perfectly circular. This does not, however, stop the purely abstract concept of a circle being useful or meaningful to us; indeed, it is only by the a priori concept of the circle that we are able to intuit the natural circular object (e.g. soap bubble) at all. The same is true of any a priori (and thereby universal) concept of “the People” or “the Common Folk”. ↩

-

This is even the case with romantic love: we dare to make that anxiety-inducing first move and ask the other on a date, as if we had known them forever, even though we have only just met them and have no idea whether the date will be a disaster or not. In other words, we dare to act as if we are a Couple even though, in actuality, we are not yet; and it is only by this (again) leap of faith that the Couple can be built in the first place. ↩

Part II: Untying the Paradox

Although any attempt to “abolish” the Paradox is basically doomed to fail—as will become clearer below—we can hope at the very least to understand it, and where it comes from. Perhaps the best way to initiate this task of understanding is to ask the following question: why is it the Paradox of the Proletarian? Why are the middle classes and the bourgeoisie “exempt”, so to speak, from this trap?

There is one particular example that I think can help us begin to answer these questions, and it’s a phenomenon known as “class tourism”1. Class tourism essentially describes a practice of certain members of the middle and upper classes, whereby they venerate and appropriate cultural symbols and practices usually associated with the working class (e.g. ways of dressing, speaking, making music, eating, etc), while still, ultimately, living a comfortable middle-class life. Through this, these symbols are emptied of their meaningful content so that they can become window dressing for these classes: it gives them a bit of “edge”, “spice”, or a veneer of “authenticity”. In other words, these practices are ripped out of their context of emergence, often one of real poverty and struggle, and are reduced to superficial appearances. (A very specific of example of this might be, for instance, white middle-class “fans” of grime or hip-hop, who usually—but certainly not always!—simply like the “beat” or immediate sensation of the music, without engaging at all with the culture behind the music, which is intimately bound up with a whole host of social, political and economic issues.)

Although it may seem obvious what the problem is here, lets challenge ourselves to make it explicit. The problem is this: these middle-class “tourists” are essentially fetishists. They fetishise working-class life, which is the same as saying that they reduce it to a set of representative images without any depth; in other words, what matters is the image of the thing rather than the thing itself. (Indeed, for the fetishist, the former comes to replace and stand in for the latter.) Consider how the favoured buzzwords of the middle-class fetishists are “real” or “authentic”, connoting how a particular style of music or cuisine has emerged from “real” people living in “real” poverty with “real” struggles, to such an extent that this actual struggle has infused the style itself with some mystical “raw” aura. Now, there’s a hilarious irony here in that, if the middle-class fetishist is appropriating something from elsewhere that isn’t theirs, then any attempt here to be “authentic” is in fact clearly inauthentic, an utterly pathetic charade2. Everyone who isn’t the fetishist can see this clearly, and laughs heartily as a result, but the fetishist doesn’t see this problem because for them the thing and the image of the thing coincide: the style and the struggle it emerged from are effectively equivalent, in such a way that the style effectively embodies the struggle behind it, and the struggle is ultimately expressible as a series of symbols. It is through this magical act of equivalence that the fetishist is able to a) feel as if they are experiencing a “real” “rawness” when engaging with working-class culture3, while also b) essentially seeing working-class culture as a series of floating symbols and styles that can be exchanged just like any other. The reader will notice a clear contradiction here—how can something be more “raw” and “real” if it is just a “floating symbol like any other”?—but it is precisely the magical effacement (read: repression) of this contradiction that defines the fetishist as such, recalling that the word “fetish” was first coined to describe the mythologies and religions of “primitive” peoples in the colonised world, specifically their attributing of magical or supernatural powers to particular objects, such as totems. Fetishism has always been an affair of magic.4

There is another way of describing this fetishism. If fetishism is based off a kind of overabundant positivity (meaning is jam-packed into very specific objects, overflowing them), then we can say that a constitutive error it makes is to ignore the negative dimension of language. Language is ultimately made possible by a murky realm outside language, a point which Alain Badiou, via Samuel Beckett, terms “the unnameable”. This sounds complicated, but there’s actually a very easy way to demonstrate it. Imagine a dog. It’s by your side, yapping at you; it’s hungry. Now try and to define this dog without using the word “dog”. (Have a go, then return to this text.) You might have come up with something like “animal with four legs often kept as a pet by humans”, then realised this wasn’t specific enough (this could include cats), so changed it to “barking animal with four legs often kept as a pet by humans”. But then you think: what if a dog loses a leg; does it stop being a dog? And what do I mean by “animal”? You clasp your hands to your head at the enormity of the task and start breaking down, realising that this entire time language had been a fragile house of cards teetering over the brink of an a-linguistic void. For as soon as you lost the word “dog”, you lost any hold on the thing you were attempting to name. No words seem to be able express the yapping thing beside you—the “definition” just isn’t an adequate replacement. Curled in a foetal position on the floor, you stare down at your leg, and all you see is the hideous thing emitting its yaps and growls. Before long, it starts gnawing at your leg for sustenance. You look into it; all you see now is an unnameable horror. The Thing; I must name The Thing, you think… finally, you exclaim “dog!!!” and suddenly, looking in its eyes again, you see a friendly, fluffy Collie licking your shin; the wound is gone.

If that demonstration descended into schlocky horror, it is because the unnameable is something naturally horrific or traumatic: hence the endless SF and horror films with titles such as The Thing, It Came From Outer Space, and, quite literally, The Unnameable. Putting that aside, the point is that language is not simply a set of labels that we stick on top of “things” that exist separately to, or before, language. Language is instead that which makes these things “things” in the first place, which cuts something out of an indeterminate, pre-linguistic multitude and gives it a name. Although this fact becomes effaced through the regular and routinised use of language, every single symbol we encounter has its genesis in this way. The fundamental trauma of language is that its conditions of existence exist outside language, at what Giorgio Agamben has called that “strange point in which language and real in a way coincide”.

So, if we return to our middle-class “tourists”, we can see that they make the quite easy mistake of ignoring or repressing the unnameable, and essentially treating the world as if it was just an endless, floating array of intelligible symbols that can be exchanged and used at whim. (The fundamental myth here is that language is its own foundation, and thus that everything can and indeed does have a name; thus we can freely appropriate symbols and names from elsewhere.) The working-class people whose “culture” (to use a rather blunt term, all too aware of the paradoxical trap that is constantly beneath us in these discussions) is being appropriated, though, know that these ways of life are not mere symbols. They emerged out of the brute, unnameable realities of their existence which no available words, styles or symbols seemed to accurately express; consequently, they had to come up with their own. Through their real struggles, they know that the unnameable is the thing that drives us to name, and to create new names. They know intimately, in short, that language has its limits; that it is a wager, a hedging of one’s bets, a leap over the unnameable.

-

Also known as “poverty tourism”. ↩

-

For clarity’s sake, this is not me arguing that it’s bad for middle-class people to partake in or enjoy the kind of working-class styles, music, cuisines etc invoked here. The issue is the way we approach these various styles that are not “ours”, which I tackle more in Part III. ↩

-

The term “working-class culture” is, of course, pretty problematic (as I mention a few paragraphs below this). As long as we are loose and charitable with how we read it however, it works in the context I have used it here. ↩

-

Needless to say, my arguments in this post are not designed to apply to these “kinds” of fetishism; instead they are a playful reworking akin to Marx’s “commodity fetishism”. ↩

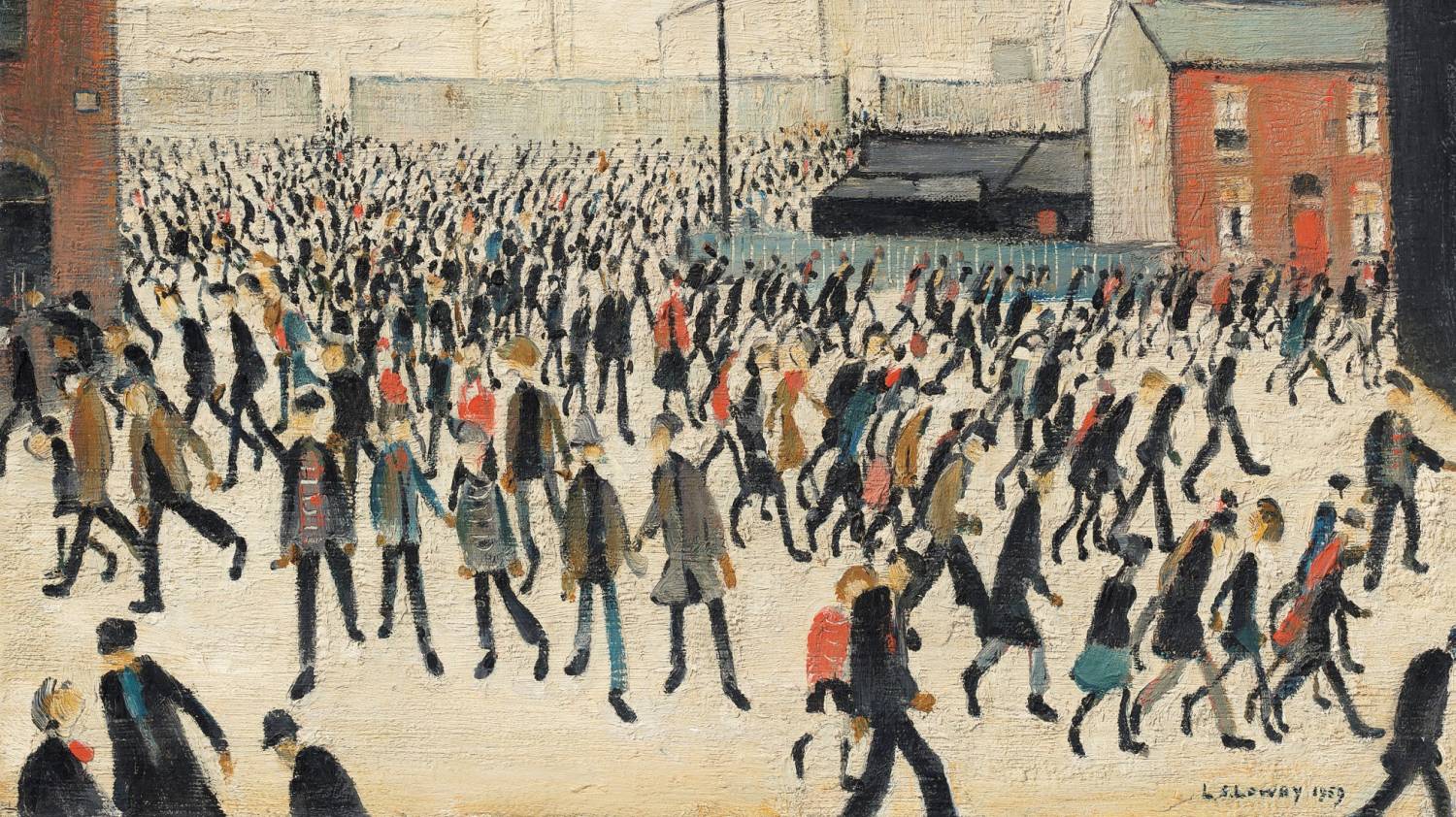

Part I: Introduction

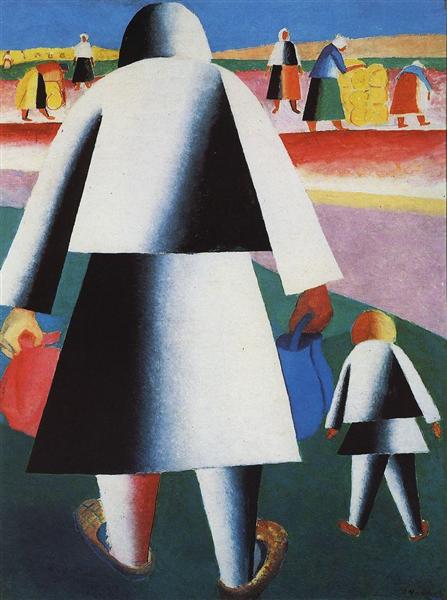

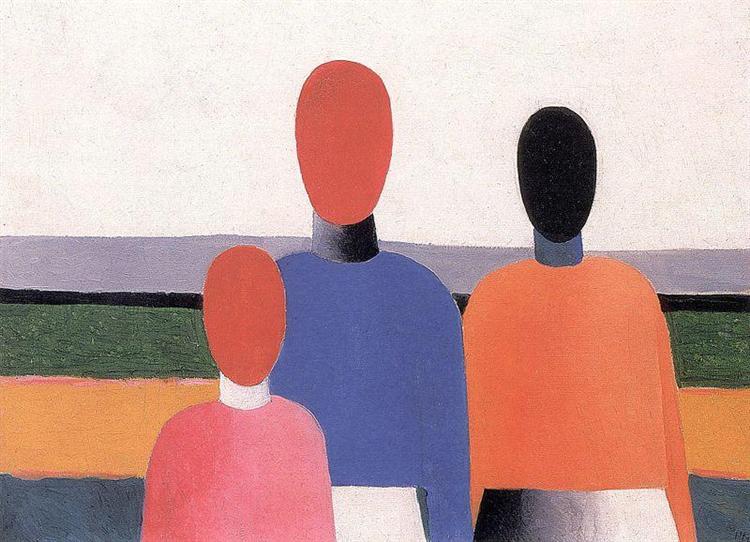

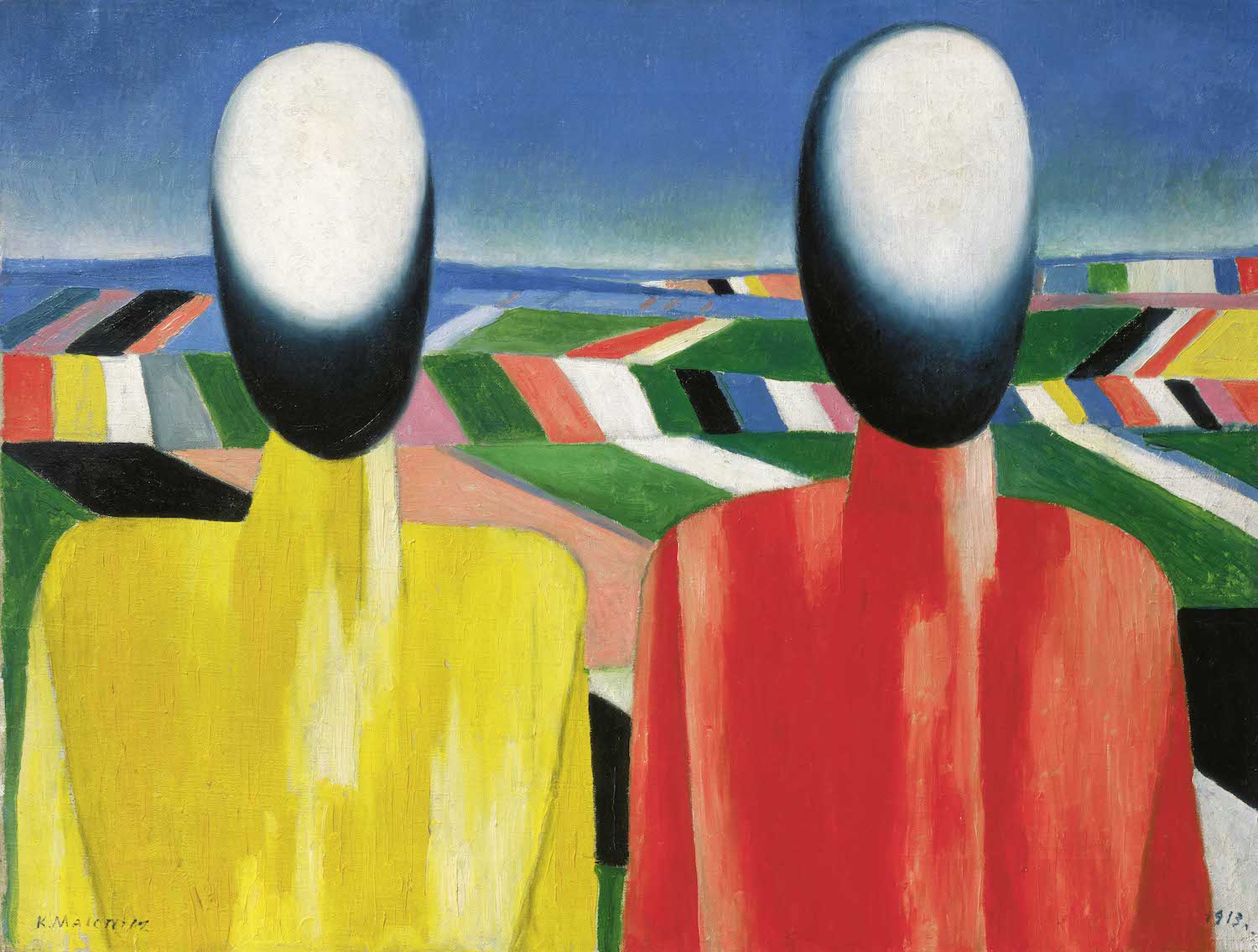

Before you learn anything about it, have a look at the artwork above. Sit with it for a while; feel it between your fingers. Notice the gradual, curving shadows of the figures’ spheroid heads; notice the way they stand beside one another; notice the stretching fields behind them.

When, in 1930, Kazimir Malevich painted Peasants, pictured above, it was intended as a solemn portrayal of the tragic consequences of the Soviet collectivisation programme that was then under way in the country. This process touched him in a personal way: Malevich had spent much of his childhood growing up—and working—on sugar-beet plantations in remote villages in Ukraine, and always felt a deep affinity with the peasant way of life. “I always envied the peasant boys who lived, it seemed to me, in complete freedom, amidst nature”, he writes wistfully in his autobiography1. “They tended horses, rode into the night, and shepherded large herds of pigs which they rode home at night, mounted on top and holding onto their ears.”

What stuck with Malevich the most, however, was the peasants’ natural predilection for art: a mixture of an artisan craftiness and a rich sense of folk mythology, symbolism, and iconography. As he writes:

The main thing that separated the factory workers and peasants for me was drawing. The former didn’t draw, didn’t know how to paint their houses, didn’t engage in what I’d now call art. All peasants did.

Later on he adds:

The village, as I said earlier, engaged in art (at the time, I hadn’t heard of such a word). Or rather, it’s more accurate to say that it made things that I liked very much. These things contained the whole mystery of my sympathies with the peasants. I watched with great excitement how the peasants made wall paintings, and would help them smear the floors of their huts with clay and make designs on the stove. The peasant women were excellent at drawing roosters, horses, and flowers. The paints were all prepared on the spot from various clays and dyes. I tried to transport this culture onto the stoves in my own house, but it didn’t work. I was told I was making a mess on the stove. In turn came fences, barn walls, and so forth.

Malevich knew this world was special because, ironically, he did not entirely belong to it: unlike the peasants, he identifies himself as living in a “second society” of “factory people”, owing to his father’s employment at the nearby sugar refinery, where he often worked night shifts. Whereas Malevich sees the peasants living a bucolic life of freedom, the factory people worked in something akin to a “fortress” in which they “worked day and night, obeying the merciless summons of the factory whistles”. “People stood in the factories, bound by time to some apparatus or machine: twelve hours in the steam, the stench of gas and filth.” Meanwhile, in the winter, as the factory people worked day and night:

…the peasants would weave marvelous materials, sew clothes; the girls would sew and embroider, sing songs, dance, and the boys would play fiddles. […] There was none of this with the factory people. I quite disliked that.

Raised amongst the peasants, then, Malevich saw clearer than most the miserable, mechanised (un)life that saps the urban working class; and so, when the Soviet collectivisation reforms came along, he could only apprehend them with horror. As individual farms were forced to collectivise and subjected to strict production rules and quotas, the previously rich cultural life and traditions of the various were assaulted and erased. Peasants were reduced to homogeneous cogs in the State’s machinery; they were, quite literally, faceless mannequins. Lives, as well as cultural traditions, were lost: the collectivisation reforms contributed to a famine that led to millions of peasants losing their lives. The Face of the Future Man, runs the title of one of Malevich’s paintings from this period: it is simply yet another blank, haggard head.

*

The back-story of Malevich’s Peasants, then, appears unequivocal: they are damning critiques of the undead Soviet machine, mournful elegies for a lost peasant way of life. But, alas, on this point I must make a confession: for quite some time now, I have seen in Peasants, and indeed all Malevich’s work from this period of his life, a quiet beauty. Until recently I had assumed that they were celebratory pieces produced in the early, heady times of the 1917 Revolution: muted, utopian expressions of the new Soviet man, stripped of all parochial identifications and hang-ups. Against bright, multicoloured fields, Malevich’s figures appear like modernist symbols of a fresh start, a new humanity, that looks forward into the future while still remaining close to their roots, quietly undertaking the essential work of tilling the soil, growing food, and feeding the people. Old yet new, cultured yet grounded, proletarian yet in power, Malevich’s mannequins gave me hope that all those wild, contradictory dreams that leftism seeks to realise were possible: because look, they’re there, on the canvas; we can see them. And if it can be captured in art – why not in practice?

And yet, as I was soon to find out, there had been a mix-up. Malevich intended exactly the opposite of the above: the peasants’ facelessness was not to be exalted as a “fresh start”, but mourned as the sign of the death of various rich cultural traditions. One wonders: how could I get it so “wrong”? How could this piece of art elicit two so completely opposed readings?

-

Malevich, “Chapters from an Artist’s Autobiography”, October journal, 1985, translated by Alan Upchurch. Available here. Citation here is from p.28. ↩

People wearing ornaments and fancy clothes,

carrying weapons,

drinking a lot and eating a lot,

having a lot of things, a lot of money:

shameless thieves.

Surely their way

isn’t the way.

Reciting some passages from it in my reading diary, I realise a significant line of affinity that I share with the Tao Te Ching: an intense disdain for busy-bodies, pragmatists and the rich, and a profound sense of care for the most common and “unimportant” things.

This pleases me very much. We can complain about “common folk” being deceived fools, too stupid for their own good, but at least in all this they are honest, and not conceited. The common person goes about their life with no pretensions to doing—or being—anything else; they go to work unenthusiastically, cook meals for their children, care for their elderly parents, call up their friends, and go to sleep. In all of this, there is never any expectation of return, never any hope of recognition or reward, and a humble acceptance of the unremarkable everyday sacrifices that uphold our entire civilisation. There is something genuinely beautiful in this.

By contrast, careerist busy-bodies and networkers always act with at least some ingrained sense of superiority, some desire to sell themselves and their ego. This vanguard of the chattering middle and upper classes enter society with the misled impression that they have the power to control it. Having listened to their teachers, got good grades, and received their university degrees, and thereby dutifully obeyed the imperatives of the bourgeois order, they then make the crucial mistake of identifying this obedience with “their choice”. The chattering careerists, with an almost comic regularity, tragically project their egos onto the most impersonal of things: society, capital, and the labour market. They hold tight to the utterly futile dream, applying for graduate jobs which they will obviously never get while refusing to apply anywhere else, turning a blind eye to the poverty, squalor and exploitation that actually characterises their life, as well as the world around them.

Having reached this position in adulthood, those of the chattering classes either fully sign up to this undead careerist path, or they realise its error, leading to the widespread phenomenon of the middle-class “slacker” (of which one could arguably categorise myself), the person who has benefitted from the advantages of a middle-class upbringing and—ironically through these advantages—come to realise their empty promise. If the chattering classes are constantly riding a never-ending elevator always reaching for that Perfect Career (And Therefore Life!) which is always just out of reach, precisely because it is an illusion, the middle-class slacker leaps off the elevator to join the common folk on the shop floor below, to try and find a genuine exit from this hellhole with them. This is never easy, because the middle-class slacker is used to riding on elevators their whole life; being on plain, flat, horizontal ground is deeply disconcerting to them. Furthermore, they also discover the horrifying sight that the elevator had been powered by the grunts and groans of the immiserated common folk below this entire time—a fact they had always taken for granted. The slacker sees the emptiness on their faces, the marks on their skin, the beads of sweat on their hairline; and yet they also see a rowdy conviviality, a laughter, alongside simple gestures of selfless kindness. Despite being on uncomfortable and unfamiliar terrain, the slacker thus begins to feel their previous emptiness dissipate within them; their hearts open, and are filled with love.

This is why it is the common folk, rather than the prosperous chattering classes, who are the most religious in any society: for it is they who most viscerally feel the brute determinism of life, the sheer necessity of self-sacrifice. It is precisely this necessity of sacrifice that is never truly learnt by the chattering classes – instead they view society entirely through the lens of exchange: everything must have a return, an interest rate. Thrown into the conviviality of the common folk, the middle-class slacker is challenged to do away with all their ingrained habits of exchange, and instead learn to sacrifice: to learn what it means to truly give. When they learn that, they will realise they were one of that strange, borderless and impersonal collective of common folk the entire time; they will learn the beauty of the faceless and the generic.

* * *

So wise souls are good at caring for people,

never turning their back on anyone.

They’re good at looking after things,

never turning their back on anything.

There’s a light hidden here.

Good people teach people who aren’t good yet;

the less good are the makings of the good.

Anyone who doesn’t respect a teacher

or cherish a student

may be clever, but has gone astray.

There’s a deep mystery here.

Hence why I always have more time for common folk than the notable, smart and successful, even if I technically have more in common with the latter. Amidst the common folk there is never anything to prove – one just is who one is. The atmosphere is essentially egalitarian: the assumption is that whatever you do or say, you will still be one of us amidst the muck, still one of us struggling by, and so there is no need or desire to compete with one another. This doesn’t mean that every conversation is amazing and fulfilling, but that they are, at least, honest and genuine, and underlaid by a firm, shared ground of mutual trust and respect. This means that when an intellectual conversation does somehow get sparked, it can develop in an authentic and above all truthful way.

Face to face with some Bright Young Thing From Graduate School who’s clued up on philosophy, however, I freeze: because I know all too well how easy it is to get drawn into stupid dick-swinging contests – conversations whose content is purely the recitation of the “right” sources and names, in order to appear intelligent and, by virtue, superior. These conversations are never fulfilling because the primary concern of each participant is not the production of a shared goal, but simply not to appear like an idiot. Unsurprisingly, this is completely counter-productive to the task of raising collective consciousness. Anxious and untrusting of each other, the conversation degenerates into a charade, subordinated entirely to appearances and self-interest. Unable to open themselves up and loosen the tight security systems of the ego, the truth which is always latent and indiscernible in any situation/conversation is prevented from coming to light; instead what we get is the tedious and undead recitation of facts and soundbites pulled from elsewhere. (Faced with these situations, I usually find the best response is to stay silent, and quietly slink off with all the other bored observers of this dick-swinging contest to talk about something that actually matters.)

Reflecting on this, I offer the following conclusion: in order to get to the stage where intellectual discussion feels genuinely enthralling and productive, one must pass through the “common” or “base” stage first – one must be willing to expose and humiliate oneself in front of the other. In short, only when both are bathed in filth and excrement can two people, facing each other, have a worthwhile intellectual conversation.

This is essentially what I have with Nick and Alex: together us three have been through the highs and the lows, seen each other at our absolute worsts, and it is precisely these acts of mutual debasement and sacrifice—in other words, a true and eternal friendship—that allow us to intellectually converse in a way that feels true and genuine. All the heavy, stifling load of egotism and self-importance have been long dropped at the door, allowing the intellect to run free.

If you think being intelligent makes you a “superior” person, then, you are still clinging all too tightly to that object that you ultimately must renounce: the ego. The development of intelligence is not the simplistic movement up a hierarchy (this is an illusion fostered by academic qualifications), but rather a paradoxical—some would say divine—movement that is simultaneously an ascension and a descension. The person digging deep into the grounds of her trauma, for example, feels as if she has been struck by the light; she feels refreshed, anew, with a new clarity of understanding and purpose regarding her life. And yet, as she experiences such beatitude, she is surrounded by dirt and soil, the raw matter of the cosmos, all the traces of her pain and suffering, her traumatic memories, worse times. This, however, is not a contradiction – rather, it is precisely what makes her enlightenment true, genuine. To truly move up is to, simultaneously, move down.

It is this dialectic of high and low that helps explain why Mark Fisher was revered so widely: because unlike all the trendy social theorists who lurk the conference halls of academia, he was flagrantly open in his acts of self-debasement. In reviewing Girls Aloud singles and Terminator films, he was essentially destroying any hope of appearing a “serious”, “highbrow” or “important” critic, or in touch with any of the hip trends in academia, cultural criticism, and so on. But this was also what endeared us to him, for it was an essentially proletarian, or “common” sensibility – for if this is what he was listening to or watching, why pretend otherwise? Why not just start there? This hard-nosed prole sensibility – a kind of unsentimental “realism”, for wont of a better term – is often corrupted into a reverence for “common-sense” and the obvious, but in essence it need not be. It is not the demand to know one’s place, to stay stuck writhing in the dirt of the ground, but the knowledge that one can only stand tall thanks to the firm and dirty ground they compress beneath them. Indeed, understood correctly, it is neither a base anti-intellectualism, nor a cloying middle-class desperation to keep up appearances, but instead a plain-clothed commitment to the Truth. It is a commitment to start from where one brutally and totally is, warts and all: to genuinely see who and where they are, rather than, as the chattering classes are wont to do, turn a blind eye.

After all, the Now is all there is; each and every one of us is happening for both the first and last time.

Start there.

Read More »

The wager of this piece is as follows: it is incumbent on communists to think the commun- of their title, stemming from the Proto-Indo-European root *ḱóm (beside; near; with) and the Latin mūnus (a service; a duty or obligation; a favour; a spectacle; a gift), itself stemming from the Proto-Indo-European root *mey — “to (ex)change”.

We begin by acknowledging that the first goal of any radical leftist political practice is the activation, or raising to the level of self-consciousness, of common ties that had hitherto been obfuscated by force and in the interest of the oppressor1. Whether it be among workers, people of colour, migrants, prisoners, women, queer people, and so on, the initial aim is always to bring people together who the powerful wanted kept apart and compartmentalised. We seek the construction of that initial rowdy meeting, where workers who have never spoken to each other despite working in the same place start talking and making bonds, where women find out they are not alone in the face of belittlement and harassment by the men they encounter, and where migrants who have long felt almost hysterically dislocated from the society into which they have migrated find others who have felt the same impacts of xenophobic alienation. To go even further, we seek the meetings after the meeting, those initial friendly conversations between the meeting’s participants on the bus home, or outside sharing a cigarette, about anything in particular… Those first signs of a budding, the sprouting of something new, matched by the excitement and nervousness about what it could become.

What is the nature of these “common ties” – what does it mean to hold in common? We can begin to reach an answer here by noting how the common is different from the equivalent or identical. While the statement “A is identical to B” proposes that A=B, “A has X in common with B” does not propose that A equals B at all – simply that they are both somehow involved with the common third term X. To state the obvious, A and B can be drastically different in numerous ways, and still have something – X – in common. (This all appears obvious, but I state it to stress the fact that while we often think of communities as founded on a principle of identity or homogeneity, the opposite is true: communities are instead founded on a principle of difference, on that “something extra” that must exceed the common term X.)

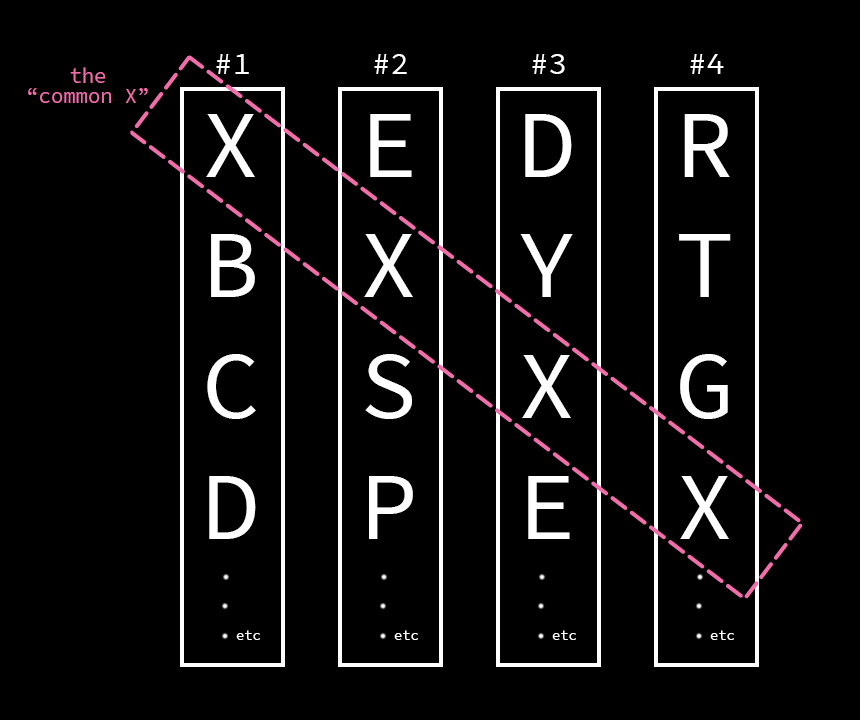

This leads us to that mysterious X – the commonly-held thing which we will hereafter term the common X. Now, this X is a strange entity: while it must possess some degree of repetition in order to hold the community together and give it some consistency, it is also something that necessarily exists in excess of any “singularity” (e.g. individual person, television programme, social media platform, whatever). The common X traverses all singularities – it cuts across and surpasses them, in order to “connect” them. Consider the diagram below2: here we have a “community” of four parts, #1-4, which all share some common characteristic, X. If we want to consider the common X in itself, rather than simply as a characteristic of some specific part, we are forced to cut across and traverse all the four parts, leading to the sketchy pink box in the diagram. This “box”, however, is quite unlike the others in the diagram, which depict specific parts with some kind of demarcating line between “inside” and “outside”. For the repeated Xs in the pink common box are not simply a collection of elements, as in a part-box; they are instead the repeated iterations of “one” consistent plateau – X – in different particulars. The common X therefore lacks any principle of interiority: to borrow a phrase from A Thousand Plateaus, the common X “exists only through the outside and on the outside”3 – interiority is alien to it. The X has a singularity and consistency, but no (self-)identity; and it is precisely this quality that allows it to hold together disparate parts, founding a community or commons.

At the “centre” of any community4, then, is this mysterious common X, this element held in common that the community in a way “hinges” around. Take, for example, the community around a particular school: that amalgamated multiplicity of friendships between pupils, after school clubs, relationships between parents, after work drinks between teachers, the conversations in the staff kitchen between cleaners on their break, weekend sports matches, school trips, and so on. Here, the common X may not appear mysterious at all – is it not simply the school, as a material “thing” made of bricks which teachers inside, etc? Yes and no: while a stable material structure is no doubt essential for a school – and thereby a school community – to exist and flourish, so long as we conceive of this structure as simply a “thing” in the commonly understood sense of the term (i.e. an “obvious” object of our consciousness that we can manipulate and control), we will never be able to explain what actually drives or constitutes the school community. For remember, the common X is not a “thing” in the usual sense of the word (i.e. an individual, obvious/transparent, controllable object), but something that traverses such individuated “things”, that cuts across and exceeds them. It is, to use the conceptual language of Gilbert Simondon, not an individual but transindividual5.

Lest this sound overly jargony, let us specify this example some more. Take two children: one is a bookworm and a teachers’ pet, and comes from a middle-class home; the other has had bouts of low attendance because of poor mental health and an unstable family life, and comes from a more working-class background. While the former thoroughly enjoys school and feels “at home” in class, going to clubs and bantering with the teachers, the latter finds the disciplinary environment of the school profoundly alienating, struggles to engage in class, and consequently thoroughly dislikes school. Both of these children are in the same school, potentially in the same class, even sat next to one another – and yet each has an experience of school that their classmate would find basically impossible to genuinely imagine or relate to. So on the one hand, we have “the school” presenting itself to us as a fun, rewarding environment; on the other we have “the school” as an alienating, harsh, and confusing institution. Bring in even more students into this example, and we could add “school as boring” to the mix, “school as racist”, “school as sexist”, “school as funny”, etc, etc – how is it that one “thing” can present itself to us with so many faces? The usual interpretation of such a problem is simply to argue that these are just different “opinions” held by the different students at the school – in this reading, the differences are “colonised” or “domesticated” by the individual subject; each different perspective on school becomes a property possessed by the individual, subordinating difference to identity. In other words, here we read the differences on the side of the individual subject(s), conceived as a separate, self-contained Wholeness. The more radical reading, however, is to posit that these internal gaps or fissures are on the side of the “school-in-common” itself – it is the school as the common X which is split, fractured, internally differentiated, and it is precisely this internal fracturing that enables it to be the basis or “centre” of the school community. When two students from the same school express different opinions about school, this tells us less about the “inner truth” of each student’s personality/individuality but rather, on the contrary, demonstrates the internal differentiation of the commonality “school” itself.

Consequently, the common X at the centre of our imagined school community is not simply “the school” as some simple object consisting of bricks and teachers, but instead what we have called the school-in-common, a strange entity that cuts across and exceeds all the singular elements that hold the school in common (students, teachers, parents, the bricks, the earth beneath it). As we have demonstrated, in order to cut across and connect singularities like it does, the school-in-common (or “common X”) cannot be a fixed, positive, transparent object: instead it is perpetually fracturing itself, emptying itself of any determinate content. The “generating principle” of any community, then, is never some Master or Leader who stands tall at the centre and proclaims to symbolise the community and speak for it “as a whole”, giving it some kind of fullness/presence. No – such a proclamation is always the retroactive attempt to paper over and fill in the self-emptying void of the common X that is the primary basis and “generating principle” for any community6. The common X incessantly splits itself, differs from itself, and it is through such self-differentiation that it becomes open to the outside, that it extends its commonality and builds/generates the community. In contrast to the figure of the Master-Leader who claims to symbolise and “be” it, the community is, then, instead always centred at its edges: it is the way a community “buds” at its fringes, self-differentiates, or changes itself that defines what it is. The community’s becoming is its being.

This is all, naturally, difficult to wrap one’s head around. Primarily, this because no one ever directly experiences the “school-in-common” in itself; the “common X” is not an object that is given at the level of our individual experience and (self-)consciousness. Why? Because it necessarily exceeds all individual experience. If it did not, we would not have a community, but rather a series of detached individual elements – the good and the bad student would be trapped inside their own personal prisons with nothing in common, least of all going to the same school. Thinking and understanding community therefore necessitates that we think in terms of difference, rather than identity – and part of such a thinking involves accepting that at the centre of any community is an absence, an incompleteness. For as soon as we identify a community with some positive object given in experience (“the centre of the school community is the school as a simple, obvious, material object”) we fail to understand the community as such, we “kill” it.7

(It is all somewhat like an asteroid orbiting the Earth; as anyone who has studied physics or mechanics knows, a thing in orbit is technically “falling” towards its gravitational centre point – in other words, the asteroid is technically falling towards Earth, compelled by the force of gravity. Due to the speed and angle of its departing flight path, however, it never reaches Earth. One can thus imagine us as aliens on an orbiting asteroid, constantly under the impression we are about to hit our gravitational centre, the mysterious X at the centre of our community – but always doomed to fail, for to hit the centre would be kill the orbit, or in our analogy, the community itself…)

-

This was originally a fragment from what was to be a multi-part series of posts on social media that I had been very gradually and haphazardly adding to since last May, and intended to publish here early this year. Other projects have come up, though, and as a whole the series feels already like something that I have moved beyond, so I have decided to drop it. This fragment, however, I still like, and think stands on its own two feet. Again, I have already “moved beyond” certain bits of it, but a lot of it still works, and it’s good to have some kind of testament to the months of work that ultimately led up to it. ↩

-

Like all the diagrams in this piece, this is ridiculously speculative. The diagrams presented here are simply little drawings I have made to set some thoughts into motion, and while they undoubtedly claim some productive and clear relationship to “the Truth”, they equally do not claim to accurately “be” or “represent” it either. (This is a bad approach to diagrams in general, anyway.) The “rigorous” logician or mathematician would no doubt balk at this approach; in particular I can imagine a set theorist picking apart and redrawing this diagram quite ferociously, reconceiving the boxed parts here as round sets, which all intersect Venn diagram-style over the shared element X. This intersection – which in mathematical notation would take the form #1 ∩ #2 ∩ #3 ∩ #4 – could then be described as its own particular set of its own, ridding the “common X” of all its “strange features” I discuss here. I can’t claim to have the knowledge to counter this, but I do have a sense that the set theory approach freezes and fixes the necessarily dynamic movement in commonality, thereby ironically misrepresenting it. However you feel about that explanation, Badiou’s Being and Event is in the post as we speak, which leans on set theory quite a lot, so this isn’t the end of this line of thought… ↩

-

ATP 2013, p.2 ↩

-

In his seminars on postcapitalist desire, Mark Fisher states how he dislikes the term “community” because it suggests an “in” and an “out” of the community. I share Fisher’s weariness about the term, but note that his uneasiness comes from a reaction to a communitarian or nationalist appropriation of the term “community” that, as the theorising in this post is explicitly shows, is in fact a botched notion of community that subordinates it to some racialised Master-Leader. The right may be the ones speaking the language of “community”, but we should be open in exposing this as a wolf in sheep’s clothing, and assert instead that a correct theorisation of community, or collectivity, is indispensable to the Left. (As an aside, it is worth noting that Fisher was perfectly comfortable with and supportive of the notion of “collectives”, stating in a 2004 blog post that “there is no more urgent task on this hell planet than the production of rational collectivities”, for example. If one is uneasy about the use of “community” in this post, then, you can simply swap out the word “community” for “collective” and rest easy in the knowledge that you have “got it”.) ↩

-

For a short but rigorous introduction to Simondon’s works, see Muriel Combes’ Gilbert Simondon and the Philosophy of the Transindividual. ↩

-

And such a “filling in” often has disastrous consequences: as Zizek notes in both The Sublime Object of Ideology and The Ticklish Subject, it is this attempt to fill in and “gentrify” the emptiness at the centre of any community that defines totalitarianism as such. The problem with Stalinism, for instance, is that the Party/Leader claims to stand in for, or coincide with, the People in toto without any leftover, meaning that any slight deviation from the Party’s/Leader’s rules – as inevitably happens, such is the nature of community sketched above – is construed as a deviation against the People, and therefore in need of violent repression. The truth of the matter is, though, that this act of deviation, far from being an act against the People, is what constitutes the People as such. ↩

-

To put a Kantian twist on it, we might say that community or commonality is the necessary precondition of individual experience as such; there is no singular individual without a community or field of commonalities that precedes them. ↩

I may as well begin this roundup with a frank admission: at the beginning of this year, I did not know how to read.

Sure, I knew the technicalities: I was familiar enough with the particular socially agreed match-up of phonemes, graphemes and meanings that constitutes the English language. Familiar and capable enough, in fact, to practically inhale vast quantities of the written word. But we should be clear in asserting that such an ability to automatically respond to linguistic cues is not the same as reading, thinking, or intellectual practice in general. While it is such a practice’s necessary precondition, it is not the practice itself, which maintains its own singularity and uniqueness. For it is one thing to inhale, quite another to extract from that inhalation the oxygen that nourishes our intellectual bloodstream.

Things are changing, though. Last month, all too late in the year, I started a reading diary as a place to log my preliminary thoughts about the stuff I was reading, which were previously transiently flowing through me only to get lost in the aether. Principally, the diary is an attempt at commitment: a practice of staying faithful to and honouring the transformative impacts that books have on me, of – in Badiou’s terminology – showing fidelity to the Event (of reading). In our first readings of books, all we are left with is an accumulation of (positive or negative) sense-impressions or thoughts (“that bit was cool” “this bit was boring” etc), and maybe a few notes in the margins. Our duty after this first reading is to almost immediately begin a second reading, which drills into those particular sense-impressions and tries to clarify them, work out what in the book caused them to happen, at a level detached from (yet immanent to) the immediate experience of reading the book. This is what the practice of keeping a reading diary allows one to do: to give ourselves up to the books, to fully and psychedelically follow the path away from our “selves” that they set in motion.

Taking its cue from the reading diary, then, the principle of this roundup is precisely the opposite of showboating. Initially, the plan was simply to post a list of what I’d read this year, as some kind of achievement – but it quickly became apparent that this would be of no use to anyone, least of all me. A list such as that is like the initial material extracted from a mine, or the raw data collected by some online marketing platform: crude, incoherent, quite simply not ready. It is an uninviting mass that, far from being galvanised by some kind of connective or inspirational principle, simply lies there as sheer magnitude. A big, mangled rock of readings of philosophy, music criticism, literary modernism, SF and gothic horror, that no one wants to touch. (And even if, perversely, they wanted to, they wouldn’t know where to begin.)

When heaved and lugged onto the platforms of social media, those digital mirrors that provide the contemporary self with the reflected image that it mistakenly identifies itself with, this big mangled rock can only be self-serving and exhibitionist; a pseudo-intellectual form of dick-swinging. And lest it not be obvious, this is precisely what this blog stands against: the transmogrification of intellectual practice – quite simply, the practice of staying true to the Truth – into a putrid careerist ego-fiction. Intellectual practice cares little for what books are ostensibly “about”; it does not read blurbs. Instead it seeks to channel the real conceptual movements that weave through texts, extending and intensifying them into new, unknown zones. It operates in the underscore.

The below, then, has nothing to do with me. I can only predictably concur with k-punk when he wrote in 2004 that “writing, far from being about self-expression, emerges in spite of the subject.” And so it is with reading: when accumulated under the subjective frame of being “things I read”, the readings below can only appear as crude material, a mass of undifferentiated junk characterised only by its magnitude. But when the raw material is felt, held, and cradled, one begins to notice patterns; protruding excesses are transformed into murder mystery clues, ambivalent signs of something far stranger – and far beyond – any personal subject. (Adorno: “Every work of art is an uncommitted crime.”)1

What follows is therefore “my 2020 reading” as it deserves to be presented and acknowledged2. Not an individual ego-fiction, but various plateaus or planes of consistency, impersonal threads of connection. Not tightly policed “schools” of interiorised thought, but the open fields of the Outside. (Deleuze-Guattari: “A book itself is a little machine… [it] exists only through the outside and on the outside.”)3

Inherently defined by such an openness to the outside, such threads of commonality naturally bleed into and cross over each other – where does one field “end” and other “begin”? – and I will likely end up repeating myself. This is no problem, though: in fact it is precisely what allows us to see the works in their true form: flaming sites of multi-vehicle pile-up, the singular points of collision and intersection of the various planes of consistency that cut through them.

Or to put it more classically, we can say that this messy excess of cross-bleed is what allows us to stop seeing books as self-contained parts, and instead as particular instances of the Universal.

When one knows this, one knows how to read.

-

Theodor Adorno, Minima Moralia, part 72, “Second harvest”. ↩

-

Editorial notes: The below includes a mixture of books and shorter length pieces including articles, essays, interviews, blogposts, etc. A few things – some of them exceptional – have been left out, for one of two reasons: (1) because they did not seem to belong to any of the common threads that were at work in my reading this year (which is fine); and (2) because I either thought they were just not very good, or I still do not “get” them, or how to put them to use. ↩

-

A Thousand Plateaus, p.2. ↩

Activists and Artists

Let us begin by proposing that “the Left”, since its inception, has been divided into two main camps: a) the “bread and butter” up-the-workers Left of the trade union movement and various activist organisations, and b) the progressive counterculture or avant-garde located around the spheres of art, music, film, poetry and so on1. While both of these aggregates are united in adhering to some kind of anti-capitalist critique, each approach and enact their critique of capitalism in strikingly different ways and languages, varyingly leading to either 1) productive mutually reinforcing collaboration or 2) bitter hatred and resentment between the two camps. For shorthand, let us conceive of this as a split between the activists and the artists. (With all the usual caveats that such a shorthand is necessarily reductive - of course activists can also be artists, and artists can be activists, and many people actually are both those things.)

What is the nature of this split?

To start with the artists, we can first note that they primarily enact their critique aesthetically: their aim is oriented around the production of a singular Work or Event that ruptures common sense and forces us to drastically rethink our place in the universe, sometimes to such an extent that it initially offends all our pre-existing tastes and sensibilities. As indicated, this approach is driven by a logic of singularity, seeking to strike that uncanny moment that is simultaneously both absolutely unique and yet absolutely universal, a kind of return of the repressed that both horrifies and captivates us.

Consequently, while the artist is (usually) highly sympathetic to the critique of capitalism, they try and integrate such a critique into a broader, more universal frame. This often makes such a critique more muffled or abstract than, say, the activist would like: a film director may decide to critique capitalism’s ecological destruction by directing and writing a film that is heavily laden with ecological themes, without mentioning the words “capitalism” or “working class”, for example, at all in it. Nonetheless, in that the film presents us with a particular vision of Nature that capitalism works to obstruct, the artwork can be said to function as a critique of capitalism.

This is because the artist seeks to conjure and use a language that is poetic rather than direct and literal. The intention is not really to use language as a tool whose only function is to “point to” things in the exterior “real” world, but to treat language as a medium to be explored, stretched, cut up, etc, as a raw material with its own Truth. To borrow a point from Badiou, the artist seeks a Truth that is not propositional (i.e. does not take the form of a proposition which we then “prove”) but poetic. Or to put it in a Deleuzian register, artistic language follows a logic of expression rather than representation2. The artistic “language” of (a) painting, for instance, is not one that ultimately seeks to refer to an exterior ground – though it may, by happenstance, do that – but rather seeks to be a ground itself, to be a new Truth of its own.

In contrast to this aesthetic approach, the activists approach their critique politically, attempting to organise the working class into some kind of collective organisation (party, union, guerrilla, etc.) held together by a common vision. Unlike artistic production, this organising is driven not by a logic of singularity but commonality: the activist does not seek to “stand out” among fellow members of the working class, like a singular artwork, but rather endeavours to be a mediator between such workers3, helping them to see past their particular differences and become conscious of their shared subjugation. The activist is a far more deferential figure than the artist as a result: they become skilled in the arts of conversation and persuasion, learning to tease the worker out of themselves and into dialogue with their fellow workers. The activist is always keenly aware of this: it is not their voice that ultimately matters, but the subjugated members of the working class that they organise with.

Alongside this organising activity, a political programme emerges, which seeks to give concrete expression to this commonality, acting as a faithful cross-section of its members’ situations and interests. What quickly becomes clear when drafting this document, answering the questions “Who are we and what do we want?”, is that what the workers hold in common is not so much a set of positive qualities or attributes, but lacks: lack of control over their work from their boss, lack of ownership over their home, lack of money, lack of respect from the police, and so on. Dark, spectral and vaporous, it is these lacks that form the truly generic set that, initially, forms the basis for the activist political organisation.

Translated at the level of the programme, such lacks dialectically become the basis for demands: open antagonisms rather than simple negations. The activists name their enemy and hold them responsible for their oppression and exploitation: the boss, the landlord, the police, the media. Through such a translation, it becomes evident that the logic of commonality that structures the political organisation necessarily leads to it being openly particular in its membership and approach4. Deferential to its members and openly antagonistic, the organisation never claims to speak, or be for, everyone, and nor could it function this way. Consequently, unlike the artwork, the political organisation is particular and pragmatic, grounded in specific concrete situations that they seek to intervene in. And it cannot be otherwise: for, as the “frame” of a situation is widened outwards and outwards, both in space and in time so as to become less and less particular, it becomes increasingly difficult to make and sustain political judgements. After all, from the point of view of deep cosmic time, does it really matter all that much if you organise your fellow workers at the job you hate and want to quit? Is going to another miserable protest worth your time? The activist can never really answer these questions, which anyway do not concern them: they care about the here and now, the blood boiling in their veins. Seeking to distance oneself from the immediacies of the present is scorned, either as lazy or aloof – a bourgeois privilege.

The artists, however, famously thrive on such distanced territory. Artistic genres and aesthetics such as the Gothic, sci-fi, and cyberpunk (to give just a few limited examples) have much to say about such cosmological, theological, ecological, technological, and philosophical concerns: the relation of man and machine, evolution, science, consciousness, aliens, God, the natural vs. the artificial… The activists? Not so much. Such distanced, abstract topics appear to have little immediate use in building the organisation.

Now, it is worth stressing that neither of these modes are better or worse: they are simply different ways of responding to a shared situation, and both can (and indeed often do) work together very productively. Today, most musicians, artists, and writers are broadly left-wing and have great sympathy and admiration for the work of organisers, particularly in unions like UVW and IWGB (the former of which now has a branch for creative and design workers). Furthermore, some of the most visible union struggles in the UK and US recently have also been in the creative sector, such as workers at the Tate, National Theatre and Southbank Centre striking over job losses two months ago, or staff at both Pitchfork and Vice forming unions which have won recognition and new contracts, as well as doing work stoppages.

Simultaneously, however, such growing class consciousness among artists and creative workers does not seem to have been met with a growing “artistic” consciousness among activists on the Left. Indeed, for much of the contemporary “bread and butter” Left, the avant-garde is still something to be treated with suspicion: a pretentious, bourgeois plaything that is unnecessarily esoteric and detached from the everyday person’s life and concerns. And this is where the carrots come in.

-

Something I spoke about in the “Corbyn, Glamour and the Working-Class Dandy” post. ↩

-

The term “expression” may sound like vague nothing-speak, but Deleuze very rigorously theorises it, and its differences from signification/representation, in Expression in Philosophy: Spinoza. ↩

-

Clearly such organisations are not just made as workers – replace “workers” with “tenants”, “people of colour”, “queer people”, “women”, where appropriate, etc. ↩

-

The terminology is used precisely here: singular is not the same as particular. Whereas “singular” directs our attention to a certain absolute uniqueness, “particular” points us to the Whole that this particular thing is part of. When we talk about a “particular apple”, for instance, we are identifying this round, green object through the Whole (Apple-ness) that it is a part of. ↩

I have never fully understood why revolution is expected to be so drab. The dictatorship of the proletariat has so often been interpreted as the dictatorship of the ugly and shapeless that it begs the question why glamour is anathema to so many advocates of social upheaval? In all of recent revolutionary history the only truly glamorous revolutionaries I can remember - Che notwithstanding, who was handsome but also a scruffy bastard - were the drag queens of Stonewall in Greenwich Village who went toe-to-toe against the homophobia of the NYPD in 1969 and scored a major victory for gay rights and the crucial liberty of sartorial self-expression. Ever since, I have been with them all the way, a true believer in the legitimacy of fighting the good fight in high heels.

…the majority of the up-the-workers Left… seemed totally unaware of the great tradition of the English working class dandy. The wideboys of the Forties, …the teds of the Fifties and the mods of the Sixties were all progressive versions of what Orwell described as ‘young men trying to brighten their lives by looking like film stars’ and George Melly later called ‘revolt into style’. The workers never wanted to look like the proles of Metropolis but they were too wretchedly paid and brutally overworked to do otherwise… One of the great attractions of the Blackshirts was that they offered unemployed louts snappy uniforms. The lone Red of my acquaintance who had both an awareness of power through style and the flash that came with it was a self-proclaimed Stalinist who rode a Triumph Bonneville and favoured Jim Morrison-style leathers and a swan-off Levi jacket, with a hammer and sickle in place of the motorcycle club patch. More than once he told me, ‘I’d join the Hell’s Angels, but it’s the bastards you have to ride with. They don’t have a clue. I mean, how many could I discuss Frantz Fanon and The Wretched of the Earth with?’

– Mick Farren, Give The Anarchist a Cigarette

The above quote, found while trawling the archives of Owen Hatherley’s old blog, succinctly gets to one of the, in retrospect, key limitations of Corbynism (and, by consequence, Starmer’s Labour).

As I have argued previously, the initial promise of Corbyn, when he was first elected, was that he was not just a rejection of the neoliberal status quo at the level of policy, but also – crucially – the level of style and culture. In the early days of his premiership, Corbyn visibly and starkly stood out against the bland austerity-lite managerialists who ran the party at the time. He didn’t look like your boss, but an eccentric regular at an urban greasy spoon, doffing a fiddler cap and filled with secrets and anecdotes from the city’s grimy underworld. Cycling away into the distance, he had lived the life we wanted to live but had always been impeded from doing so by capital: he was one of us, in all our imperfections and rough edges. The difference between him and the grey vultures, circling around the already-ravaged carcass of New Labour, was palpable (as the painfully awkward picture below visualises).

The limitation of Corbyn’s “alternative” style, however, was that it was largely negative in character: it rejected the black suit and white shirt by forgetting the suit altogether and unbuttoning the shirt’s top button, rather than wearing something else entirely (a la Che or the Stonewall drag queens). Hence the frequent denigrations of Corbyn’s “scruffiness” – to be scruffy is always defined in relation to a dominant ideal which it fails to meet through a messy excess (long hair, unclean clothes, etc). The scruffy can be easily denigrated because it is not a style that stands on its own terms – it is only the failure of another, dominant, style.

Instead of continuing this negative trajectory through to its conclusion, however – which would have seen him doubling-down on his scruffiness and lack of “professionalism” in order to create a new, positive, alternative style – Corbyn caved to the neoliberal style council remarkably quickly. Beige suits were replaced by dark ones by the time the 2017 general election campaign came around, and such a stylistic capitulation was only further entrenched by Labour’s success at that election, which ostensibly dictated that the party must look like a “government and waiting” and Corbyn a “future Prime Minister”. Consequently, 2019 election Corbyn seemed to have lost all the spark and difference of 2017 Corbyn: years of “image management” and trying to out-government the government during the charade that was the Brexit withdrawal process had smoothed out all his edges, turning him into just another functioning component of the cynical electoral machine. (Something that unsurprisingly led to Corbynite Labour’s defeat – Corbyn was never elected or designed to be a functioning cog, but a spanner lodged in the mechanism, rupturing and destroying it. This was the role he could convincingly and persuasively play, not “future Prime Minister”.)

Read More »

Halfway through Samuel Beckett’s excellent Malone Dies, the titular character details a highly evocative visual metaphor that quickly gets right to the heart of the Beckettian project:

… I feel it my duty to say that it is never light in this place, never really light. The light is there, outside, the air sparkles, the granite wall across the way glitters with all its mica, the light is against my window, but it does not come through. So that here all bathes, I will not say in shadow, nor even in half-shadow, but in a kind of leaden light that makes no shadow, so that it is hard to say from what direction it comes, for it seems to come from all directions at once, and with equal force. (p.58)

You can picture it in your mind’s eye: a dull light that illuminates basically nothing apart from indiscriminate amorphous pools of dark colour that we can barely perceive, that for all intents and purposes is not “light” at all. And yet, this is not simply darkness either… there is something that we sense, but without any of the clarity that light is supposed to bring…

It is not just Malone’s room that is bathed in this eerie “leaden light”, which he evokes multiple times throughout the book: it is seemingly the entirety of Beckett’s oeuvre. Beckett’s characters are often decrepit, impotent, forgetful and elderly figures that stalk not just at the fringes of society (for example in mental institutions) but also at the fringes of the human itself. Constantly reflecting on and editing the texts which they are purportedly the author, flitting from one topic to the next, his characters seem to lack any of the regularity or constancy that define human interiority. And yet, they stubbornly remain human: with a dark and bleak sense of humour, they continue to think, walk about, and even have sex. Much like the leaden light, we can grasp at “something” with Beckett’s characters, but paradoxically because of this, they remain unclear, dark, “nothing”.

It is precisely this commitment to the eerie, contradictory fringes that makes Beckett’s books often challenging and difficult to read: absent a plot or characters in any substantial or coherent sense, the major footholds a reader typically depends on when reading are gone. For most people, this amounts to a cardinal sin, and an immediate turn-off: why read a book where nothing happens? Where we know essentially nothing about the characters involved? Why are there pages, indeed a whole physical book, when really there should be none? Indeed, for most people these are entirely legitimate questions, and the “common sense”, instinctual reaction to Beckett’s works would be to stop reading after 20 pages and tell everyone you know how boring the book was. But such criticisms, rather than seriously invalidating Beckett’s works, actually demonstrate the radicality of the philosophical claims they make on us. For in order to seriously engage with and enjoy them, Beckett’s works demand nothing less than this: that we adopt a whole new ontology, an ontology right at the limits of ontology itself.

The central philosophical question prompted by Beckett is this: how do we think nothingness without turning it into a “something”? How do we think a being that, paradoxically, is nothing? What kind of “being” is the leaden light?

Read More »

This is the introduction to what was going to be a longer essay that I started writing about a month and a half ago, but lost its way and I eventually gave up on. It seemed a waste to not do anything with it, though, and I actually think it works better as an isolated fragment. So enjoy…

Read More »

What is Pop? Or equivalently, what is the popular? This is the question Simon Reynold’s book Rip It Up and Start Again forces us to confront, particularly towards the middle of the book, where the focus pivots from post-punk to early 80s New Pop: the moment many post-punk artists such as Scritti Politti and The Human League get tired of post-punk’s puritanical commitment to fringe experimentalism and turn their sights to the mainstream, the popular. What’s valuable about Reynolds account here is that it gives us the perspective of approaching Pop from the outside: we are introduced to a rag-tag clan of artistic misfits who are desperately trying to crack the code of the popular, to break into the Top 40 and become stars, as if it were some alien language beamed in from another galaxy. It is these people, those who consciously have to crack and break into it, who really understand Pop, rather than those who have unconsciously been interpellated or conditioned by it (such as the “popular” kids at school).

This is because the popular – Pop – has very little to do with what “is” popular, statistically and numerically. Pop is not simply a kind of molar statistical aggregate, a name for a thing lots of people know of or do. Commuting to work – to conjure up the most banal example I can – is something millions of people do, but one would really be stretching to call commuting “popular”, or “Pop”. It’s part of the grey background of everyday life: precisely the thing that Pop strives to stand out against and rupture. Pop needs to be a spectacle, a concentrated singularity, quite literally the centre of attention, in order to exist. Pop is a centralisation or it is nothing.

Read More »

It’s been incredibly humbling over the past few weeks to see people value, share, and stick up the election posters I designed in a spur of the moment one evening, as pictured above. While I of course designed them to go viral, I never actually expected it to happen, let alone become the inspiration for a massive banner made by Manchester Momentum and cited in a recent VICE article by Lauren O’Neill. (I’m yet to get over my excessive self-criticism which deems every piece of work I complete, including this very post, as irrelevant, useless, and a waste of everyone’s time; I’m working on it.)