30 Dec 2020

The underscore__ 2020 Reading Roundup

I may as well begin this roundup with a frank admission: at the beginning of this year, I did not know how to read.

Sure, I knew the technicalities: I was familiar enough with the particular socially agreed match-up of phonemes, graphemes and meanings that constitutes the English language. Familiar and capable enough, in fact, to practically inhale vast quantities of the written word. But we should be clear in asserting that such an ability to automatically respond to linguistic cues is not the same as reading, thinking, or intellectual practice in general. While it is such a practice’s necessary precondition, it is not the practice itself, which maintains its own singularity and uniqueness. For it is one thing to inhale, quite another to extract from that inhalation the oxygen that nourishes our intellectual bloodstream.

Things are changing, though. Last month, all too late in the year, I started a reading diary as a place to log my preliminary thoughts about the stuff I was reading, which were previously transiently flowing through me only to get lost in the aether. Principally, the diary is an attempt at commitment: a practice of staying faithful to and honouring the transformative impacts that books have on me, of – in Badiou’s terminology – showing fidelity to the Event (of reading). In our first readings of books, all we are left with is an accumulation of (positive or negative) sense-impressions or thoughts (“that bit was cool” “this bit was boring” etc), and maybe a few notes in the margins. Our duty after this first reading is to almost immediately begin a second reading, which drills into those particular sense-impressions and tries to clarify them, work out what in the book caused them to happen, at a level detached from (yet immanent to) the immediate experience of reading the book. This is what the practice of keeping a reading diary allows one to do: to give ourselves up to the books, to fully and psychedelically follow the path away from our “selves” that they set in motion.

Taking its cue from the reading diary, then, the principle of this roundup is precisely the opposite of showboating. Initially, the plan was simply to post a list of what I’d read this year, as some kind of achievement – but it quickly became apparent that this would be of no use to anyone, least of all me. A list such as that is like the initial material extracted from a mine, or the raw data collected by some online marketing platform: crude, incoherent, quite simply not ready. It is an uninviting mass that, far from being galvanised by some kind of connective or inspirational principle, simply lies there as sheer magnitude. A big, mangled rock of readings of philosophy, music criticism, literary modernism, SF and gothic horror, that no one wants to touch. (And even if, perversely, they wanted to, they wouldn’t know where to begin.)

When heaved and lugged onto the platforms of social media, those digital mirrors that provide the contemporary self with the reflected image that it mistakenly identifies itself with, this big mangled rock can only be self-serving and exhibitionist; a pseudo-intellectual form of dick-swinging. And lest it not be obvious, this is precisely what this blog stands against: the transmogrification of intellectual practice – quite simply, the practice of staying true to the Truth – into a putrid careerist ego-fiction. Intellectual practice cares little for what books are ostensibly “about”; it does not read blurbs. Instead it seeks to channel the real conceptual movements that weave through texts, extending and intensifying them into new, unknown zones. It operates in the underscore.

The below, then, has nothing to do with me. I can only predictably concur with k-punk when he wrote in 2004 that “writing, far from being about self-expression, emerges in spite of the subject.” And so it is with reading: when accumulated under the subjective frame of being “things I read”, the readings below can only appear as crude material, a mass of undifferentiated junk characterised only by its magnitude. But when the raw material is felt, held, and cradled, one begins to notice patterns; protruding excesses are transformed into murder mystery clues, ambivalent signs of something far stranger – and far beyond – any personal subject. (Adorno: “Every work of art is an uncommitted crime.”)1

What follows is therefore “my 2020 reading” as it deserves to be presented and acknowledged2. Not an individual ego-fiction, but various plateaus or planes of consistency, impersonal threads of connection. Not tightly policed “schools” of interiorised thought, but the open fields of the Outside. (Deleuze-Guattari: “A book itself is a little machine… [it] exists only through the outside and on the outside.”)3

Inherently defined by such an openness to the outside, such threads of commonality naturally bleed into and cross over each other – where does one field “end” and other “begin”? – and I will likely end up repeating myself. This is no problem, though: in fact it is precisely what allows us to see the works in their true form: flaming sites of multi-vehicle pile-up, the singular points of collision and intersection of the various planes of consistency that cut through them.

Or to put it more classically, we can say that this messy excess of cross-bleed is what allows us to stop seeing books as self-contained parts, and instead as particular instances of the Universal.

When one knows this, one knows how to read.

Music and Post-Punk

Simon Reynolds, Retromania

Simon Reynolds, Rip it Up and Start Again: Post-Punk 1978-84

Mark Fisher, “K-PUNK, OR THE GLAMPUNK ART POP DISCONTINUUM”, k-punk (X)

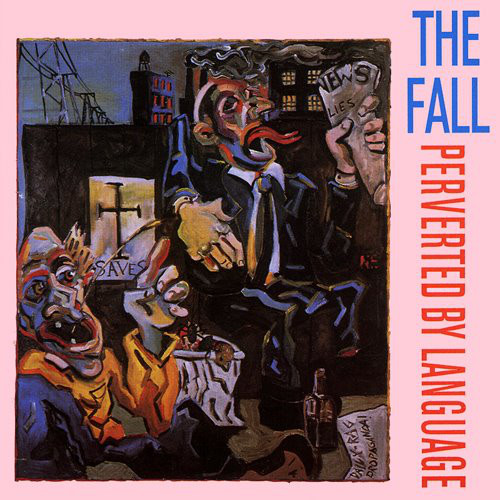

Mark Fisher, “Memorex For the Kraken: The Fall’s Pulp Modernism (Parts I-III)”, k-punk (X)

Mark Fisher, “…and when the groove is dead and gone..”, k-punk (X)

Mark Fisher, “Nihil Rebound: Joy Division”, k-punk (X)

Mark Fisher, “A Rupturing of this Collective Amnesia”, k-punk (X)

Aloysius, “Burrowing in For the Long Winter (Parts I-IV)”, (blog). Part I begins here

Honourable Mentions

Greil Marcus, Lipstick Traces

Agnes Gayraud, Dialectic of Pop

Robin Mackay, “Towards a Transcendental Deduction of Jungle”. Available here

Simon Reynolds, “The Rise of Conceptronica”, Pitchfork. Available here

History repeats, or reiterates, itself in interesting ways. Amusingly, when I was a teenager, I went through a phase of desperately wanting to be a music journalist, to the extent of actually doing a week’s work experience at the NME when I was 15. It was far less glamorous than it sounds, and I spent most of the time flicking through the archives from the 80s and 90s rather than actually doing any work or making any connections. In fact, if anything the experience left a bad taste in my mouth: even as a teen desperate to be cool, I was put off by the smug hipsterism that swaggered around that office, and well aware that the flagrant bullshitting that constitutes most music criticism leaves a pungent stench. This was career writing, writing subordinated to the imperatives of profit and branding, utterly uninterested in channelling the sonic intensities that move and inspire us in music. Wanting more but ignorant of where to look, I subsequently gave up on any hope in music criticism, and gradually the discovery of new music began to lose the utopian potential it has promised when I was a teenager discovering, say, Entertainment! for the first time.

The above readings, in their own ways, exhibit a kind of music criticism that moves differently – a music criticism that awoke me from my slumber. They are readings motivated not by personal point-scoring and put-downs, but a genuine fandom and conviction, a commitment to the aesthetic projects of the music they write through. The pinnacle of these is, as readers of this blog will be utterly unsurprised by, Simon Reynold’s Rip It Up and Start Again, which inspired multiple blogposts here at the beginning of the year. Rip It Up is nothing less than the post-punk bible, a book full to the brim with creative-destructive energy, not simply a “history on/about” post-punk but a vital continuation of the post-punk project itself. It is warming reminder that there was a time where large numbers of underground artists and musicians who refused to see art as simply a machine for producing pleasure, and indeed frequently dared to actively piss off their audiences, true to the punk spirit. (For a summary of some of these stories, see my blog post on Rip it Up from March.) In an age where postmodernist PR “is so ingrained that you’re as likely to hear vacuous spiel about “markets” and “target audiences” from freelance YouTubers and writers as from an actual marketing executive”4, these stories are almost unimaginable – which is exactly why you should read them.

In short, the challenge that post-punk throws down to its listeners is to do more with the music we engage with than simply use it as an individualised palliative for when we are stressed after work. No more simply phasing out to lo-fi hip hop beats to numb all your vital functions to – instead, to paraphrase Zizek’s refrain from the end of The Ticklish Subject, the pieces above exhort us to dare: to dare to think that music can be more than “just” music, that music makes a claim on us that is more than “just” sonic, or musical – that perhaps in every song that moves us is the key to a different, better, mode of life. Above all, they dare us to do the thing that postmodern consumerism constantly works to prevent: to be a fan, to actually give up a part of our lives to the countercultural pulse at work in the music, to turn music into a different way of living, rather than just another moment in the circulation and exchange of commodities.

And it is the blogposts on music by k-punk, above, that will always show us that such a thing is possible: witness how he unfurls Joy Division into a medium for thinking depression and the crumbling of the post-war settlement; or how he turns The Fall into a key that unlocks a whole submerged history of the English grotesque, as embodied by Lovecraft, Eliot, and M R James…

Addendum: A special callout here to one of my favourite set of blogposts from this year, “Burrowing in For the Long Winter”, by blogger Aloysius. Over four parts, Aloysius develops a fascinating theory of musical creation and evolution, revolving around three stages, or moments: the “bedroom phase”, the “scenius”5, and the “Master’s study”. I’ll pass on fully detailing the theory – just read the posts – but what is satisfying in “Burrowing” is the careful and patient explication of a path that to be honest any creative, not just musical, practice can follow in order to continually surpass and develop itself. There is a path here, a kind of road to a better life: something that Spotify, YouTube and Anthony Fantano can never really deliver on.

SF, Gothic, Existentialist Horror

Mary Shelley, Frankenstein

Flannery O’Connor, A Good Man Is Hard to Find

Simone De Beauvoir, All Men are Mortal

Philip K Dick, Ubik

Philip K Dick, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

Margaret Atwood, Surfacing

What perhaps all the fictions above present us with is an eerie sense of vertigo: the gradual pulling away of the floor, or presumed reality system, from beneath our feet. They are books for ripping off the plaster and temporarily feeling the gravitational pull of the abyss tug at your skin: metaphysical deep cleanses, reboots of your reality’s dominant operating system.

This feeling of uncanny vertigo is quintessentially Gothic; it emerges from something I call the Gothic inversion, condensed in the following mantra: make the natural artificial; make the dead alive; make the human inhuman. But rather than simplistically move from one “pole” to the other, the Gothic inversion forces these two seemingly contradictory instances to coincide with one another, often in one singular being. Frankenstein’s monster is, of course, the archetypal example of such a monstrosity, but we find the monstrous surfacing throughout all these books: in the notorious androids of Dick’s Do Androids Dream… who, with their implanted memories and analytical prowess one must submit to a rigorous test in order to ascertain whether they are human; as well as in the protagonist of Simone De Beauviour’s All Men Are Mortal, Fosca, a Genovese prince from the 13th century who, after drinking a potion that makes him immortal, we witness gradually descend into an undead husk of a man, even in the heady fervour of Revolutionary France.

In Flannery O’Connor’s exceptional short story collection A Good Man Is Hard to Find6, by far the most “grounded” and “realistic” of the fictions presented above, this vertigo is instead translated into the feeling of being blindsided, of being unexpectedly touched by God’s grace. O’Connor’s Catholic fictions are typically populated by common folk from the farms of post-war America’s rural South, who undergo an intense and religious experience of Christian revelation before, usually, dying. In their intensity and unexpectedness, these deaths – alongside the “deaths” of the stories themselves, which are short and concentrated – work to express something far grander and meaningful than simply the end of a human organism. O’Connor, a devout Catholic, was far too smart, though, to simply reduce this grander meaning to dogmatic Christian orthodoxy7. Instead, her stories work expertly to channel the spiritual or cosmological essence – rather than dogmas – of religion; they are stories perpetually bursting out of their containers exhibiting a meaning that is inherently excessive, always slightly beyond our grasp.

This is the Gothic inversion in its religious, spiritual, or occult register: what is most particular (“good country people”) is made to coincide with the most universal (God); what is most everyday is made to coincide with the most divine.

The Absolute

Spinoza, Ethics

Alain Badiou, Saint Paul: The Foundation of Universalism

Eugene Thacker, In The Dust Of This Planet: Horror of Philosophy vol.1

Eugene Thacker, After Life

Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morals

Gilles Deleuze, Expressionism in Philosophy: Spinoza

Flannery O’Connor, A Good Man Is Hard to Find

Eugene Thacker, “Darklife: Negation, Nothingness, and the Will-to-Life in Schopenhauer”, Parrhesia #12. Available here

I, like I suspect many others, grew up treating religion as a complete irrelevance. The son of two middle managers who benefitted from free higher education and the late-eighties boom in the British economy, growing up there was no need for any kind of faith in a world beyond our immediate realities. Thatcherite capitalism was made to cater for people like my parents at the time: young middle-class graduates who worked in London offices and had just got their first mortgage at the age of 25, and were having a ball of it. Everything worked; things were comfortable, seamless. And when you’re part of the lucky strata of people that the exterior world caters to, what reason is there to turn to God? Or politics? Or struggle? Religion was just a set of stories handed down from a past age that we subtracted all meaningful historical and theological content from: ultimately, it was just about being a nice neighbour, being kind, platitudes like that. Indeed, religion was treated as something so devoid of meaningful content that, if I am remembering the story right, my father in his youth once became a born-again Christian simply to meet girls.

If, in line with the above picture, a certain hard-headed empiricist strain of British “common sense” sees religious belief as fundamentally irrational, what many of the texts above do – particularly Spinoza’s and Thacker’s – is show that in fact any rationality (rationalism?) worth its salt necessarily ends up confronting the issue of the Absolute. (Which, when conceived theistically, = God.) Thacker’s After Life in particular deserves commendation for being an interesting and accessible introduction to Scholastic thought, which it turns out tackled the question of God/the Absolute through a ruthlessly analytical thinking concerned with thinking through various logical contradictions that emerged from thinking at such a large metaphysical scale. Consequently, as one reads these texts and follows their lines of logic, one slowly begins to build a haphazard conception of the Absolute in one’s head, to the point that one day, suddenly, it all seems to make sense: the grand churches, the preaching, the devotion, everything. One doesn’t necessarily agree with it – organised religion is in general pretty disagreeable – but it certainly no longer appears as empty multiculturalist window dressing. Instead, it becomes clear that something is at stake in religion, something in it still matters, blowing the restricted worldview of a middle-class multiculturalism wide open…

Towards a Militant, Universalist Politics

Slavoj Zizek, The Ticklish Subject

Alain Badiou, Ethics: An Essay on the Understanding of Evil

Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth

Sam Kriss, “White Skin, Black Squares”, Idiot Joy Showland (blog). Available here

Mark Fisher,”We dogmatists” (X), “The Proletarian Cogito” (X), and “Punishment Enough” (X), k-punk.

Honourable Mentions

Alain Badiou, Infinite Thought

Dominic Fox, Cold World

Two facts, that 2020 has made all too clear. One – it is generally agreed upon that the world is pretty bad, for obvious reasons. Two – in addition to this, it is not incredibly difficult to quickly obtain masses of information detailing how and why it is bad: not only is a Google search only a few taps away, but social media influencers are always desperately eager to “break down” “what’s going on” in this or that part of the world, replete with pastel-coloured graphics and cutesy cartoons. All well and good – the problem, though, is this: neither of these two facts add up to any kind of meaningful, or useful, political practice. In fact, more often than not they produce its inverse: detached posturing, knee-jerk reactions, and a hopeless, depressive nihilism, void of joy or purpose. The frenzied immobilisation of the scroll.

Accordingly, it is precisely the question of practice that the readings above are concerned with. What they are resolutely not are systematic expositions of how capitalism works, or detailed histories of such and such a struggle – they are not “informational”, or even, ironically, “practical”. Instead – and crucially – they are texts about what it means to be a militant: what it means to be in the depths of a struggle, and how to stay true to it. More than any Instagram infographic, they understand that every militant, universalist leftist politics is built on Red belonging, the feeling of “belonging to a movement: a movement that abolishes the present state of things, a movement that offers unconditional care without community.”

Extra Film Rec: Göran Hugo Olsson’s 2014 documentary Concerning Violence is a superb film adaptation of The Wretched of the Earth, organised around archival footage discovered from the national liberation struggle in Mozambique in 1960s and 70s. You should watch it.

The Ballard-Spinoza Flatline

Spinoza, Ethics

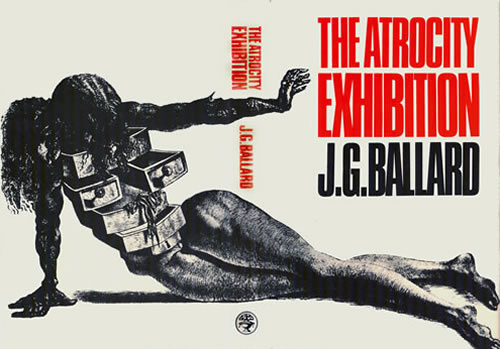

J. G. Ballard, The Atrocity Exhibition

J. G. Ballard, The Drowned World

J. G. Ballard, Concrete Island

Gilles Deleuze, Spinoza: Practical Philosophy

Gilles Deleuze, Expressionism in Philosophy: Spinoza

Honourable Mentions

Simon Sellars, Applied Ballardianism

Errol Harris, Spinoza’s Philosophy: An Outline

A proposition: you won’t understand the radicality of Ballard until you read Spinoza, and you won’t understand the radicality of Spinoza until you read Ballard.

Ballard constructs with his fictions what Spinoza geometrically deduces in his Ethics: a zone of radical immanence that Mark Fisher termed in his PhD thesis the Gothic flatline. Note how the characteristic move at work in all of Ballard’s fiction is the drawing of equivalence of two drastically different scales: “individual” psychologies are portrayed as following the same logics of vast (concrete, apocalyptic, media-blitzed, etc) landscapes, or explained in reference to the deep time of Earth’s slow geological formation (most famously in Dr. Bodkin’s “Theory of Neuronics” from The Drowned World). The implication of this Ballardian move is precisely that all particular phenomena can, once considered at a suitable level of (geometric/mathematical) abstraction, be radically connected or equated with one another; and this “suitable level of abstraction” is nothing less that the Gothic flatline mentioned above, a plane of immanence on which everything can collide. To cite a common refrain from Crash, semen mixes with engine coolant…

What one finds in Spinoza, then, is the rationalist explication of this Gothic flatline, coolly deduced as if it were a mathematical proof. This is perhaps most succinctly demonstrated in a remark Spinoza makes in the preface of Part III of the Ethics, where he states: “I shall consider human actions and appetites just as if it were a question of lines, planes, and bodies.” The scandal of Ballard is evident here, just in more muted tones: human emotions, appetites and strivings, far from being our precious possessions, are instead ultimately, like the rest of Nature, the results of impersonal chains of cause and effect which can (in principle) be expressed as abstract geometric equations…

“The Cold Rationalist program is Abstract Ecstasy”: k-punk and Mark Fisher

Matt Colquhoun, Egress: On Mourning, Melancholy, and Mark Fisher

Mark Fisher, “INDIFFERENTISM AND FREEDOM” (X)

Mark Fisher, “Spinoza, k-punk, neuropunk,” (X)

Mark Fisher, “Psychedelic reason” (X)

Mark Fisher, “WHY BURROUGHS IS A COLD RATIONALIST” (X)

Mark Fisher, “FOR YOUR UNPLEASURE: THE HAUTER-COUTURE OF GOTH” (X)

It has recently occurred to me how deeply religious a figure Mark Fisher was, though not in the sense that you’d usually understand that term. Earlier this year, I saw a tweet from some insufferable Philosophy Twitter account or another proclaiming how they were getting increasingly annoyed with Fisher’s work, because it was not rigorous or systematic enough8. This is a category error: it is like complaining that an apple does not taste like an orange. But apples aren’t oranges, and Mark Fisher was never a philosopher, nor really even a cultural critic. Instead he was – and I use these terms as neutrally and secularly as possible – a saint, a preacher, a deeply committed man fuelled by the urgency of a spiritual and intellectual project9. In a deeply irreligious age, he was a man who possessed that rarest of things: faith.

It takes more than faith and intellectual flair to make a saint, though: it takes a sacrifice, a suffering. Consider Saint Paul in Corinthians II 12.10: “That is why, for the sake of Christ, I delight in weaknesses, in insults, in hardships, in persecutions, in difficulties. For when I am weak, then I am strong.” Paul’s “delight” here is precisely the practice of putting his sufferings to work, of working through them rather than seeking to paper over or “heal” them, for he knows that such a labour is what allows him to become “all things to all men”10, to be a saint. Lost in the depths of the k-punk blog, one finds a similar Pauline “delight” in Fisher’s work, though it is a delight shorn of all pleasure or good feeling: it is a purely cold, intellectual delight. It soon becomes clear that it is precisely this saintly exercise that has drawn Fisher such a devoted following, who have their mass every year at the Mark Fisher Memorial Lecture at Goldsmiths: he seemed to live our suffering for us, so as to help us better understand it and escape it.

None of this saintliness emerged from a blind obedience to organised religion, or a devotion to some benevolent creator-God, though. Quite the opposite: Fisher’s commitment was to a kind of cyberpunk Spinozism that he took to calling in a spate of blogposts from late 2004 “Cold Rationalism” – a program for “Abstract Ecstasy”11. One of the central tenets of Cold Rationalism is that emotions do not belong to us as individual persons, but are instead engineered through abstract chains of cause and effect: for instance, we are always happy/sad/anxious about something or other, even if we are not fully conscious of the object or the reason behind it. In principle, then, one could follow this chain of cause and effect up and up, into ever higher levels of abstraction, without ever leaving the raw emotional starting point: in other words, we would lose no explanatory power over our emotions by considering them in terms of abstractions – in fact if anything, we would gain a greater understanding of them. (The Ballard-Spinoza flatline in full effect.) What this demonstrates nicely is that, while couched in in a cool cybernetic sheen, Cold Rationalism is not some theory-bro rejection of (fuzzy, illusionary, “not real”) feelings and emotions in favour of the real cold hard “facts” of “abstract machinic processes” or whatever. No – for Cold Rationalism is not a rejection of the personal, but its unfolding.

The Cold Rationalism label was soon dropped as Fisher got older, but its general program was one that he held faith in until his death: one can distinctly see traces of it in works like Capitalist Realism and “Good For Nothing”, where he argues for a politicisation of mental health precisely through a Cold Rationalist perspective of treating emotions as impersonal, rather than primarily individual and psychological. Knee deep in the brute suffering of depression and anxiety like so many others, then, Fisher never stopped holding his grubby hands up to the sky, pointing towards some “higher” power (of course conceived secularly as some Spinozist plane of immanence consisting of abstract geometric collisions between bodies). And mediating between the high and low like this, he could never be anything other than a saint, a sorcerer, a shaman.

Beckett & Literary Modernism

Samuel Beckett, The Unnamable, Malone Dies, Molloy

Samuel Beckett, Endgame

Virginia Woolf, The Waves

“In the appreciation of a work of art or an art form, consideration of the receiver never proves fruitful. Not only is any reference to a certain public or its representatives misleading, but even the concept of an ‘ideal’ receiver is detrimental in the theoretical consideration of art, since all it posits is the existence and nature of man as such. Art, in the same way, posits man’s physical and spiritual existence, but in none of its works is it concerned with his response. No poem is intended for the reader no picture for the beholder, no symphony for the listener.” (Walter Benjamin, The Task of the Translator)

Psychoanalysis, Sex

Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks

Sigmund Freud, Beyond the Pleasure Principle

Sigmund Freud, Civilisation and Its Discontents

Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil

Slavoj Zizek, The Sublime Object of Ideology

Jean Baudrillard, Seduction

“A Quick and Dirty Guide to Psychoanalysis”, Psuedoanalysis (blog). Available here

Endnotes collective, “We Unhappy Few”, Endnotes #5. Order here

Mark Fisher, “Weird/ Psychoanalysis”, k-punk (X)

Mark Fisher, “Let me be your fantasy”, k-punk (X)

Conrad Jarrett, the teenage protagonist of Robert Redford’s 1980 film Ordinary People, sits in the office with his psychoanalyst, Doctor Berger. He’s recently been released from a psychiatric hospital after trying to kill himself, traumatised by witnessing his brother’s death in a boating accident. Now returned both to school and his upper-class family, he finds himself struggling with his cold, status-obsessed mother and his overbearing father. Tetchy, he fidgets in his seat; an ill-fitting, washed-out green sweater constricts him, muffles his body. “Look, I’m just wasting money today, I’m not going to feel anything”, he numbly declares. “I’m sorry.”

All too aware of the thinly-veiled repression at work here, Berger swiftly rebuffs him. “No, sorry’s out. Come on, something’s on your mind.” Conrad proves resistant; Berger, straight-talking and sarcastic, continues to provoke him. The tension escalates. “Look, why’re you hassling me, trying to make me mad?” Conrad replies, agitated. “Are you mad?”, Berger inquires. “No!” Conrad retorts, madly.

Berger ups the stakes. “Oh cut the shit! You’re mad! You’re mad as hell! You don’t like being pushed, so why don’t you do something about it! Tell me to fuck off, I don’t know!” Automatically, Conrad complies – but within a second he reels himself back:

C: “…no, I can’t, I can’t do this..”

B: “Why not!”

C: “no… it takes too much energy to get mad.”

B: “You know how much energy it takes to hold it back?”

C: “When I let myself feel, all I feel is lousy.”

The injunctions of the upper-middle-class superego – get good grades, be polite, land yourself a well-paid career – are beginning to peel away. Beneath the manifest content of “I don’t feel anything” is a latent, traumatised core that is grotesquely protruding; the taut surface of the ego, under pressure from internal and external stimuli, is about to burst. Berger sarcastically twists the knife, and can only smile at the result:

B: “Oh I beg your pardon, I never promised you a rose garden…”

C: “Oh fuck you, Berger..”

B: “What?”

C: “Fuck you!”

B: “Yeah!?”

C: “Fuck you!!!”

B: “That’s it!”

C: “Jesus, you’re really weird, what about you, what do you feel, huh? Do you jack off, or jerk off, or whatever you call it?”

B: “What do you think?”

C: “What do I think? I think you’re married to a fat lady and you go home and fuck the living daylights out of her!!”

B: “Sounds good to me.”

Conrad exhales deeply and lies down on the couch; relief and surprise mix in his face. Pleased, Berger stands over him.

“Little advice about feeling, kiddo. Don’t expect it always to tickle.”

Geophilosophy / Transcendental Materialism

Anna Greenspan, Capitalism’s Transcendental Time Machine. Available here

Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus

Sigmund Freud, Beyond the Pleasure Principle

Eugene Thacker, In the Dust of This Planet

J. G. Ballard, The Drowned World

Thomas Moynihan, X-Risk: How Humanity Discovered Its Own Extinction

Reza Negarestani, “On the Revolutionary Earth: A Dialectic in Territopic Materialism” (available here)

Robin Mackay, “A Brief History of Geotrauma”. Available here

Ccru, “Barker Speaks”. Available here

Amy Ireland, “The Revolving Door and the Straight Labyrinth: An Initiation in Occult Time (Parts 0-1)”, Vast Abrupt. Available here

The Anti-Apocalyptus Newsletter, “Interview with Thomas Moynihan: “The discovery of extinction is a philosophical centrepiece of the modern age””, Available here

Mark Fisher, “NONORGANIC MEMORY”, k-punk. Available here

Honourable Mentions

Peter Godfrey-Smith, Other Minds

Yuk Hui, Recursivity and Contingency

If psychoanalysis is a trusty pickaxe, patiently digging away at the human psyche through the modest means of conversation, geophilosophy is a pneumatic drill. A mad prospector, speaking in pseudo-scientific tongues, it drills so deep down that it shatters the very ground that it was operating in; amongst the wreckage, it finds itself on an open plateau, fragments floating all around it, unsure what to look for. By this point the human form has lost all psychic and somatic integrity, and it suddenly appears as if the histories of abiogenesis (the birth of the organic from the inorganic) and geological stratification, amongst other things, are the lost keys to unlocking the secret of its thought.

Geophilosophy stops and ponders. “Scientists estimate that approximately ninety percent of the cells in the human body belong to non-human organisms (bacteria, fungi, and a whole bestiary of other organisms)”, Eugene Thacker notes. “Why shouldn’t this also be the case for human thought as well?”12

(Cyber/Xeno/Etc) Feminism

Sadie Plant, Zeros + Ones

Luce Irigaray, Speculum of the Other Woman

Andrea Long Chu, Females

Mark Fisher, “Continuous Contact”, k-punk. Available here

Lucca Fraser, “XF Seminar Postmortem”, Feral Machines (blog). Available here

Amy Ireland, “Scrap Metal and Fabric: Weaving as Temporal Technology”, 0AZ (blog). Available here

Sadie Plant, “The Future Looms: Weaving Women and Cybernetics”. Available here

Ed Berger, “Turning On The Eternal Network”, Reciprocal Contradiction (blog). Available here

Aly Chase, “An Autodidact’s Guide to Accelerationism”, Specular Anomalies (blog). Available here

Did you know that what laid the technological foundation for the binary code that underlies all our contemporary information and communications infrastructure, including the very device you are reading this on, was a loom? In 1804, French merchant Joseph Marie Jacquard invents the Jacquard machine, a device attached to a loom that programmes it to weave according to a series of punched cards, which express the various warps and wefts of weaving as a matrix of zeroes (no punch) and ones (punch). Fast forward to the 1950s: adopted by computer scientists, these punched cards are now read by the IBM 711 as part of the IBM 7090 mainframe computer at NASA’s headquarters, which Dorothy Vaughan, African American mathematician and human computer, teaches herself to use while hundreds of other Black women work as human computers below, making the essential calculations needed to make space flight possible (as dramatised in the 2016 film Hidden Figures).

Thus we arrive at one of the central theses of (cyber/xeno)feminism: women have had an affinity with machines from the start. For where masculinity is governed by sight (everything must be “made clear”, held at a distance from the seer, brought under control, and made to fit the form of the One, the point where all the rays of light converge in the eye), the woman-machines work by touch: always feeling their way, plugging into new machines, weaving new lines of code, experimenting, letting the touched object touch her back. Women as zero, and all the better for it. Hence Freud’s famous questions – what do women want? How do we “solve the riddle of femininity”? – and Irigaray’s retort: “It is still better to speak only in riddles, allusions, hints, parables. Even if asked to clarify a few points.”13

Essayists

Sam Kriss, “How to disdain your dragon”, Idiot Joy Showland (blog). Available here

Sam Kriss, “Teenage bloodbath: the 2010s in review”, Idiot Joy Showland (blog). Available here

Huw Lemmy, “I stole my sister’s boyfriend”, utopian drivel (newsletter). Available here

Huw Lemmy, “Big Night Down the Drain”, utopian drivel (newsletter). Available here

Strip it back to basics. Language is an abstraction that necessarily exists at some distance from the concrete realities of our everyday experiences, and it is this abstraction that makes fiction – and, indeed, art – possible. It is the fact that linguistic symbols are never fully tethered to their meanings that allows them to be used in different ways, both fictional and poetic.

It is perhaps sad that most “non-fiction” writers – including myself – rarely stop to consider this. For the fact is that even in the most dry, factual writing, we are telling a story, weaving a fiction. We can even go so far to claim that, in a certain qualified sense, every piece of writing is a piece of fiction14. That artistic, poetic element might be disavowed, but it is always there.

Historically, there has been a certain breed of writer who, aware of this fact, has sought a kind of third way between fiction and non-fiction; one who has a keen appreciation for the art of writing, but sought also to chain such an art to the brute actualities of the Real – to make a claim not simply on what could be, but what is. There are various names for such an increasing outdated type of writer – the homme de lettres (man of letters) or “public intellectual”, to name two – but perhaps the most succinct is the essayist.

It is precisely the art of the essayist that Huw Lemmy and Sam Kriss practice. Steeping their contemporary commentaries in references to classical literature and art, they are both figures who are oddly out-of-step with the present, but all the better for it: for it is the being out-of-sync with the real movements of history that, ironically, puts one most in-sync with them.

Lemmy and Kriss do nothing less than weave a kind of poetics of the present; they take the media-blitz of contemporary life, convinced that we can glimpse the Truth purely by “looking at the data” and running it through a statistical model, and carefully reassemble it into a tale, a narrative, of which we are the characters. Reading them, you realise that this is what has been missing all along.

RIP Josh

Chris Strafford, “Working for the Revolution in Rojava: An Interview with Josh Schoolar”, Prometheus Journal. Available here

Some may baulk at it, but I retain an undeniable fondness for the term “comrade”, indeed the very notion of comradeship. Social democrats like to substitute it for “friend”, put off by the militancy of the other term, but something crucial is always lost in this process: the universal promise of communism. For unlike friendship, which is always particular and local, comradeship spans the world. It is a cold, impersonal love, and all the more intense for being so.

Capital proclaims a false, or botched, universality: for while it has succeeded in sweeping the globe and making money an abstract universal equivalent, such that money and labour can be exchanged from basically any point on the globe, it has only been able to do this something that it must always traumatically repress: the global subjugation and exploitation of the working class. As such, as Marx rightly argued, it is the proletariat who is the true universal subject of history, the grotesque symptomatic excess that Capital must lock away in its cupboard in order to maintain its image of “free trade” and “liberty”.

Every act of working-class struggle then, is charged with something beyond itself: the potential to, if followed to its full conclusion, bring down the whole universal edifice of Capital, to multiply across the globe. Solidarity is the practice of self-consciousness of such a universality, and the subject instituted by solidarity is the comrade. The comrade has no personal, fleshy connection to any of the struggles she hears about from across the world, but nonetheless cannot help but be committed to and invested in their success. When she hears of their triumphs, she cannot help but be moved, energised, as if it were she herself who had struggled to victory. Similarly, when she hears of their defeat, she cannot help but be moved to tears, placed in a deep, abyssal anguish. These were people she never knew, and yet they were closer to her than her family.

This is how I felt about Josh Schoolar, a man I never met and yet always hoped I would. In September, Josh tragically passed away at the age of 23: in his short life, he had already travelled to Syria, aged 21, in order to support the antifascist struggle in Rojava by standing on the frontlines against ISIS in the region, and been an active tenant and community organiser as part of ACORN in Manchester. In all these activities, Strafford’s interview makes clear, Josh was a friend to many: well-liked, respected, and always up for a pint and/or chat. But we can go further than this: Josh was not just a friend, but a comrade. In that he sacrificed so much in his personal life for the benefit of those immediately at risk from fascism in the Middle East (the interview details how his family home was subject to regular police raids due to his time in Rojava, for instance), in that he dared to give his left-wing principles a living, breathing reality through praxis, Josh mattered not just to those he knew in the flesh, but to the whole impersonal collective of comrades struggling across the globe. It’s for this reason that I, effectively a stranger to Josh, would nonetheless always turn to him for inspiration: he was living proof that the Cause was not simply a set of dead letters on a page, but a real historical movement, charged with urgency , potency, and above all joy. In an age of mass political melancholia, the importance of a figure like this – like Josh – cannot be understated. It is yet another reason why his youthful passing was so painful and tragic.

Perhaps, though, we can take some kind of solace in the widespread grief that has followed Josh’s death. Perhaps, gently rotating it slowly in the sunlight, we can see not just the anguished cries of loss and mourning, but also the sheer strength of the cold, impersonal love that binds us comrades together, that makes us grieve so deeply in the first place. For if the comrade’s entry into the Cause necessarily involves some leap of faith into the darkness, a frightening departure from their prior identifications and particular communities (family, nation, friendship group, etc.), let us, in the wake of Josh’s death, keep this close to our hearts: on the other side, there will always be the universal commune of comrades to catch and look after you – no matter who you are, or where you’ve come from.

Footnotes

-

Theodor Adorno, Minima Moralia, part 72, “Second harvest”. ↩

-

Editorial notes: The below includes a mixture of books and shorter length pieces including articles, essays, interviews, blogposts, etc. A few things – some of them exceptional – have been left out, for one of two reasons: (1) because they did not seem to belong to any of the common threads that were at work in my reading this year (which is fine); and (2) because I either thought they were just not very good, or I still do not “get” them, or how to put them to use. ↩

-

A Thousand Plateaus, p.2. ↩

-

To quote myself from the Rip it Up summary post… ↩

-

A concept of Brian Eno’s, detailed by Aloysius in Part II. In Eno’s words: ”I came up with this word “scenius” – and scenius is the intelligence of a whole… operation or group of people. And I think that’s a more useful way to think about culture, actually. I think that – let’s forget the idea of “genius” for a little while, let’s think about the whole ecology of ideas that give rise to good new thoughts and good new work.” ↩

-

Which, along with Ballard’s The Atrocity Exhibition and Dick’s Ubik, wins the prize for the best “fiction” book I read this year. ↩

-

For her reflections on being a Catholic fiction writer, see the essay “The Church and the Fiction Writer” here. ↩

-

This is heavily paraphrased. I have better things to do than to find the tweet. ↩

-

Lest this sound like an incredibly stretched metaphor, it is worth pointing out that Simon Reynolds has noted Fisher’s religious qualities numerous times: take this 1999 interview with a young Fisher as part of the Ccru where he is described as “a cleancut young man who speaks with an evangelical urgency”, or Reynold’s foreword to the k-punk anthology, where he casts Fisher as a member of a dying breed, the “music critic as prophet”. ↩

-

Corinthians I 9:22. ↩

-

Beginning to glimpse the “evangelical” dimension yet? ↩

-

Thacker, In The Dust of This Planet, p.7. ↩

-

Speculum of the Other Woman, p.143. ↩

-

Which, just to make it extra clear, is not the same as saying that it is “false” or “not real”. ↩