29 Jun 2021

Loving Folk (Part III)

Part III: Proletarian Love

Truth is not an unveiling which destroys the secret, but the revelation which does it justice.

—Walter Benjamin

At the risk of seeming ridiculous, let me say that the true revolutionary is guided by a great feeling of love. It is impossible to think of a genuine revolutionary lacking this quality.

—Che Guevara

If the entire problem of the Paradox was precisely that of fetishism, of romanticising things, then we can see immediately that this whole time, without realising it, we have been meditating on one central issue: love. If there is one thing that the Paradox demands of us, it is to practice a true and universal love; indeed, it is precisely this kind of love that proletarian politics aspires to.

As the Che quote above acknowledges, this does, initially, sound vapid, meaningless, and trite. However, in that any meaningful social revolution presupposes some kind of egalitarian fraternity of people who come together under the banner of a shared Cause, it is impossible to deny that the revolution implies revolutionary love, or at the very least some sort of revolutionary belonging. Let us call this revolutionary love “proletarian love”, and the subject that practices this love the proletarian or the comrade. In light of the discussions of the Paradox in the previous two parts, here we round off this essay by thinking through the following question: what is this proletarian love? Which perhaps is equivalent to asking that one vexed, eternal question: what is true love?

*

I don’t pretend to have any kind of definitive answer to this question, and I am not about to present a “Theory of True Proletarian Love” (which sounds like just about the least loving thing I could do right now). Nonetheless, I do think it’s possible to creep closer to some kind of answer by framing the question negatively, and asking instead: what is proletarian love not?

First off, proletarian love is not a love “for” the working class. This is simply the problem of fetishism all over again, the reduction of the working class to a particular series of fixed attributes and symbols. Instead, our aim is a kind of love which loves the working class insofar as they are stand-ins for all of humanity; in other words, a universal love. In Part II, we described this universality as concerned with a kind of “brush with the void”: the universal expressed itself through the working class via their encounter with the unnameable void at the heart of everything, for example when they attempted to start a community project solely through the resources they had available to them, and without any funding, recognition or validation from the State. Although the working class could be said to have a “privileged” relation to this void (also known as “epistemic privilege” by standpoint theorists and Mark Fisher), in principle anyone can—and indeed more often than not do at some point—have this kind of “brush with the void”. It is in regards to this encounter with the negative that our proletarian love is universal, as will be explored more shortly.

At the same time, however, it is important to clarify that this proletarian love is not universal in the sense that, say, hippies understand it, as a kind of uniform declaration of “peace and love”, or a chilled-out pacifism. This makes a mistake that we also identified in the previous part: the mistaking of universality for identity or uniformity. To practice universal love is not to show the same undifferentiated love to every particular thing we encounter. This, clearly, is not “love” in any meaningful sense: if you claim to equally love both the slave and the slave-trader who whips them, each of them accordingly know your love to be absolutely meaningless. It seems inescapable, then, but to argue that all love is inherently engaged in the activity of taking sides: love fixates on singular things and elevates them above the rest; it orders and prioritises.

And so we find ourselves at an impasse: our universal proletarian love must on the one hand a) aspire to universality, and yet on the other hand also be b) ruthlessly partisan; it must seek a grace and forgiveness that can extend to all, and serve the interests of the whole of humanity, and yet at the same time vehemently draw its dividing lines, say “no” to the bourgeois powers that be, and stand up against oppression and exploitation. So proletarian love in some way loves all humanity; but in another way, it detests the bourgeoisie, and it spits on the careerist demagogues that so frequently lead the people astray. Is this not a contradiction? How can one claim to love all humanity and yet basically hate one small, albeit powerful, section of it? Does this not defeat our entire project?

No, and for this reason: the particular and the universal are not separate “things”, categories or labels but rather, by necessity, dialectically related. In other words we reach the universal through the particular, and not in spite of it. Indeed any concept of “universal” without the corresponding concept of “particular” is quite literally empty, something akin to the hippie’s “universal love” referred to above.

So to reiterate: proletarian love is something that strives to speak for (all) the People—in other words, the Common Folk—but does so through engaging in divisive, antagonistic political struggle. It is a kind of commitment to the Common Folk, the “true”, anonymous People lurking underneath the false images of the People that claim to be it (national flags, emblems, monarchs, and so on).

Let’s try and make this a bit more concrete; how would one feasibly practice proletarian love? How does one reach the universal “through” the particular? Our starting point is to remember that though we seek to act as (=on behalf of) the People, we never encounter people as the People, that anonymous, faceless public: we only ever interact with the particular people that we come across in our particular lives. So we begin with those often mundane, everyday moments that we are all so familiar with: a friend is complaining about their relationship, a colleague is moaning about their work, a family member is struggling to get the healthcare they need, and so on. Now, suppose we take the second example here: you are on your lunch break at work and your colleague, who you are quite friendly with, is having difficulties with their manager. Out of a fraternal love, you resolve to help them; after all, it could have been you with the difficulties, and in that situation the friend/colleague would have done the same for you. The colleague figures it’s just a small personal dispute, and they need your help preparing for a meeting with the manager in private, which you oblige to. However, after a little thought, it becomes clear that this situation could not just have affected you two, but almost the entire workplace, and indeed almost the entirety of the public, in principle. This changes things: it means helping your colleague prepare for a backroom meeting with their manager where they can privately resolve their differences no longer feels like a fair path to take. Instead, you and the colleague resolve to, rather than treat this issue as a private one between two individuals, open the issue up: to the other workers, to the public — in other words, to the Common Folk. You call a union meeting and get the workers talking to one another; you write up a press release about your actions and send it to the local newspaper. In short, you transform a private issue into a political issue; you turn a “for us” into a “for all”; you elevate fraternal love (the love between friends) into proletarian love (the anonymous love that exists between the People, as strangers, akin to “the love of one’s neighbour” in the Christian tradition).

It is this act of opening up that is the act of proletarian love par excellence, because it is precisely this that allows a particular struggle to connect with a whole host of others and begin to metonymically “stand in” for them all, and therefore begin to truly express the universal (= the People = the Common Folk). Had the friend kept their workplace complaint to themselves, this universality that the particular issue was “nested” within would never have been unravelled, and we would never had had the People chanting on the streets; we would never even believe such a thing possible.

Now, this feeling (or lack thereof) of possibility is precisely why we characterise this entire process as “love”: because it involves faith, commitment. For as any activist knows, the People do not exist in actuality yet: they have to be built. (This is precisely what distinguishes the Left from the Right: the Right assumes the People always-already exist in an identifiable form.) The People, the Common Folk, are an abstract, ideal, a priori and (Zizek would say) “impossible-real” universality that has no actual existence right now, in that we do not live in a wonderful fraternity of equals who treat each other with total selflessness and kindness. This, however, does not stop the concept from being useful, and indeed necessary for political action1. It is, after all, literally impossible to think any kind of genuine politics without some kind of a priori notion of the People baked in from the start: all political struggle is grounded on the assumption that, at some level, the People genuinely are all equal, and all equally free, and that this a priori state has been corrupted by some injustice that has introduced inequality and hierarchy into the system. Of course, we know that this is basically a fiction, a mythology, but at the same time we cannot do without it: the alternative is to assume that instead of being fundamentally equal, humanity is fundamentally unequal, and this, naturally, simply ends up in strictly hierarchical, caste-like societies which could be said to lack any meaningful definition of “politics”, because everyone simply is forced to stay in their place rather than make claims on some shared resource. Instead of this arrangement, the proletarian dares to make that leap of faith that characterises all love2: they dare to act as if that a priori ideal—the People, the Common Folk—already exists, they dare to speak to, and as, the People, even though this subject does not exist yet, and is always, perennially, to-come. And finally, crucially, it is ironically only by acting as if this object really exists that we eventually actually make it exist. It is only by daring to believe that “the people will be free” that we eventually assemble the chanting mass on the streets that seems to genuinely sound the birth-pangs of a genuinely free People. The process here is always the same: the leap of faith retroactively constructs the ground it leaped from; the proposition back-engineers its own proof. (In CCRU-inspired theory circles, this process of fictions becoming real is known as “hyperstition”. In common parlance? “Fake it ‘til you make it”.)

*

Things, tragically, are rarely so simple. As the heartbroken lover can attest to, love builds its castle on precarious grounds; the elevation of one thing above everything else is always a risky affair, doomed to, eventually, collapse. If love is the practice of continually upping the stakes, then this means necessarily upping what can be lost, what can be taken from you. Love is not love if it cannot all go horrifically, explosively wrong, completely and utterly ungrounding you. In short, love always has something negative about it; it dispossesses you. That is the price you must pay.

Experientially, we know this to be true for romantic love, but it is equally true for proletarian love. Proletarian love, like all love, draws a dividing line: and this has the effect of not just hardening the solidarity of “us”, the proletarians, but also “them”, the bourgeoisie. Love has the tendency to simultaneously produce beauty and ugliness: the joy felt as workers come together is almost incomparable in its sublimity, but the price paid for this is the constant risk of firings, workplace harassment, sleepless nights, financial difficulties, legal battles, broken friendships, and so on. To accept the call of proletarian love, then, is immediately to accept the call of struggle: of threats, dangers, and precarity. This is all bad enough in our romantic lives; but in that proletarian love aspires to universality, aspires to the making of history, things can get even worse. At the highest extremes, it is one’s life that one puts on the line; it is no wonder that most of us balk at this beyond a certain point.

And when it is a question of showing a proletarian love in the name of leftism, that well-intentioned racehorse that seems doomed by cosmic fate to perennially lose, it is even less of a surprise that the ideals of proletarian love are, in practice, rarely realised. Everything seems set up to fail; we dutifully go to marches, set up reading groups, go canvassing, vote for the right people, volunteer, and chair meetings, but the world, stubbornly, remains Bad; the People, similarly, refuse to be built. Even Corbyn, that most meek and vegetarian of men, was too much for the British public; and now we lay here in a post-Corbynite malaise, a stultifying Starmer-styled cynicism…

*

Leaving aside the example of an ordinary coin which Christian charity lets fall into the palm of the beggar, any true gift is reciprocal. He who gives does not deprive himself of what is given. To give and to receive are the same.

—Jorge Luis Borges, The Limit

Amidst the all-too-tempting nihilism, however, there is one unaddressed issue: since when was love an exchange? Does the comrade love the People as currency to purchase a revolution? Do we love our friends in the expectation of some kind of “reward” or “return” from them later? Does romantic love simply boil down to a sexual exchange, cashed in through the act of sex? The answer is obvious: no. Everyone intuitively knows that any fraternal relationship with another person is immediately spoiled the moment it becomes “transactional”, because this implies we are using the other person, rather than respecting their differences as a free and equal individual. Rather than a logic of exchange, then, what drives love is the logic of gift, or sacrifice; in other words, a giving that lacks any expectation or intention of return. Again, this is something we intuitively know: we know, for instance, that a friendship is really only put into practice the moment Friend A is struggling with something, and Friend B resolves to support them, despite the severe disruption this may put on their normal everyday life, and despite how little B may actually want to give this support (not in the sense that we want our friend to suffer, but that we lack time, energy, and resources to give). Friendship, in other words, is truly realised and consummated in the moment of dispossessive struggle, and it is only really in these depths of struggle that the sturdy, loving bonds of friendship are forged. When we say love is based on giving, then, there is a sense in which this is giving in the sense of giving (ourselves) up. What makes the love (fraternal, romantic, familial, or otherwise) authentic and true is the occasional practice of something sacrificial.

Consider a hypothetical example. If your friend, Sam, phones you in the middle of the night saying they’re lost in the countryside near(-ish) where you live and they need picking up, in order to be a true friend you simply must drive out and pick them up. There is no alternative. Every fibre of your being resists this—you have to be up early in the morning—and yet you simply cannot leave Sam there. And even if it’s not you who picks them up, it will be some other friend who goes out of their way to do it. In a crisis situation like this, ultimately someone has to pick up the slack; the buck has to stop somewhere. The ruthless calls of necessity stubbornly refuse to go away; perhaps it is the very answering of these calls that is love.

Now of course, in doing a favour such as this, we do have some kind of expectation: that, should we be in a similar situation as Sam, they would do the same for us. This, however, should not be mistaken as a “return” or “payback” for the favour of picking them up. The key word is “should”. The performance of the favour is, after all, essentially open-ended: Sam may never end up performing a similarly big favour on our behalf, and yet this fact doesn’t bother us at all, and certainly doesn’t stop them being our friend. (If it did, we could not really say Sam and us had a true friendship; in that we kept bitterly trying to “cash in” the favour, we would essentially be turning the relationship into a cold, loveless transaction.) So although Sam may say “I owe you one” in the car on the way home, we should be very clear in stressing that this relationship is not one of debt. The miracle of friendship is that it is a relationship of continued cycles of gifting, sacrifice, and favours, and yet also one of a persistent, stubborn equality. The sacrifices we perform in friendship should place us in debt: instead, we remain fraternal equals. What we have here, then, is exactly the opposite of a debt-relation, which, as David Graeber makes clear repeatedly in Debt, always expects repayment. Any debt implies the chasing of that debt. This is exactly what is absent in true fraternal, familial or romantic love.

Nonetheless, as he hinted at above, there is a kind of cyclical pattern to friendship, indeed all love: although we do not “repay” or “cash in” the favours and sacrifices of friendship, they aren’t exactly meaningless either. We don’t just let go of the sacrifices as if they were nothing; on the contrary, they matter a great deal, and give the friendship its strength. So if they are not “repaid”, so to speak, but nor are they simply brushed off, what happens to these sacrifices of love? How are we to conceptualise them?

*

The amorous subject experiences every meeting with the loved being as a festival.

—Roland Barthes3

The answer lies in a subtle, but totally transformative, shift in terminology. Instead of the gifts, sacrifices and favours of friendship being repaid, we say they are redeemed. Parsing the difference in meaning of these two terms is surprisingly tricky, not least because contemporary consumer culture has effectively equated the two terms: as we all know much too well, redemption no longer refers to salvation, but rather, pathetically, to gift cards. Nonetheless, the distinction between them is definite, and should be explicitly stated.

The distinction can be understood as follows. In repayment (in other words, in debt-relationships), there is a harsh distinction between the two parties involved: the creditor and debtor are presumed to be totally separate, and different, from one another, and there exists between them no other obligation bar the one instituted by the act of loaning. Additionally, this is not just a binary, but a hierarchical binary. One party—the creditor—is always dominant, because the thing that is loaned is their property: they own it, and they expect it back as such. This is a key characteristic of debt-relationships: property never truly changes hands. One owns, the other rents, and nothing is ever, truly, given. (The debtor even owns the time that lapses over the course of the loan; hence the existence of interest.)

By contrast, in redemption (in other words, in relationships of fraternal, familial, romantic, or proletarian love, which for shorthand I call love-relationships), the two figures, the giver and the receiver, are the same. Indeed, it is precisely this coincidence of giving and receiving that is the miracle of love; we can give or sacrifice huge masses of time and energy for our friends and lovers, and yet never feel like it has been taken from us. Nothing is a debt; everything is a gift. You may initially hate giving Sam a lift in the middle of the night, but as soon as they get in the car, “it’s nothing”. Perhaps there is even a spontaneous joy to it; either way, it strengthens your relationship in a way that you are, ultimately, grateful for.

Now, how is this coincidence of giving and receiving possible? It has to do with what we could term the cyclical or ritualistic nature of these love-relationships. Love bends time into a circle: all friends act as if they have been, and will be, friends forever. There is only love insofar as there is a regular cycle of rituals that constitute that love: these can be as simple as yearly holidays, weekly trips to the pub, or the daily kisses between lovers before they head off to sleep. And so it is in that, in the throes of love, time seems to stop4. Each visit to the pub condenses into one point all the past and future visits; each kiss between lovers condenses into one point all the past and future kisses. And when time here as simply become a series of punctuated cycles, what use is debt? Debt demands an end to debt, a fixed return date; but in love, there’s always time for another round…

The cyclical nature of love expresses itself not just in regards to time, but also in regards to property. Whereas in debt relationships the loaned object stubbornly remains the property of one dominant party, in love relationships there is always a transfer of property rights: something that was previously the property of one becomes the property of all. A friend offers to host an event at their house; a lover cooks a meal for the other; a comrade buys a sheet of cloth that their collective will turn into a banner. There is a name for this: pure giving, or the perfect coincidence of giving and receiving. The lover gives something of theirs up to the relationship, they willingly dispossess themselves of something; but immediately, in the very act of giving, they receive it back, in communal form. For the lover is “in” the relationship, the friend “in” the friendship group, the proletarian “in” the Common Folk; as such, when they give up or sacrifice something for the relationship, they never truly lose it, but instead consent to approach it with the burden of the love-relationship/community that we are a part of on our shoulders — which, as we then realise, is always the truest way to approach it. In this way, love gives us access to Truth. And so:

- 1) Redemption is the coincidence of giving and receiving

To phrase this philosophically, if there are always 1) the abstract, universal, necessary conditions of existence for any individual which always exist before them, and then 2) individual itself, what the act of pure giving by the individual achieves is 3) the realisation of these abstract universal conditions concretely, by actively building some communal love-relationship. In other words, it is the loving act of pure giving that makes us concretely, brutally and psychedelically realise that we were never actually “ourselves” as foundational individuals, but always the product of a community, a scene, a historical lineage or tradition; and it is precisely the realisation of these collective lineages that is the construction of a new collective lineage that faithfully does true justice to, and “passes down”, the prior one. Considered in these terms, it is easier to see why love-relationships follow a logic of redemption rather than repayment. In love-relationships, we are not “returning” something that the other person has given us or sacrificed for us; such a thing we know to be impossible. (How would one “return the favour” or “pay off the debt” to those—usually their parents—who raised them? It is quite literally an absurd question.) Instead, we are continually seeking to give life to these collective lineages through our individual action; in other words to redeem them, to carry or pass them on through an act of pure giving. This results in:

- 2) Redemption is the coincidence of the individual and community (or tradition)

Another seemingly trivial example. When the friend buys a round at the pub, acknowledging that she was the only one that did not the previous week, this is not “in exchange for” the rounds that were bought the week before by the others. That is not what is going on here. Instead, there is a sense that each friend, every time they buy a round, is rescuing or saving (in other words, redeeming) the friendship from non-existence. Every friendship, indeed love-relationship, is at continual risk of falling apart; for without the ritual, without the habit, it is nothing. And so, even though we know that maybe friend X will never pay us pack, we must act as if they will – we buy the round. This is why this is not a “repayment”: because the act of buying another round (which in our analogy here, = “pure giving”, for the buying of a round is simultaneously the receiving of a future round) concerns not only the past (the rounds that were bought) but also, integrally, the future. Buying a round not only redeems the previous rounds, but also allows future rounds to exist. And so:

- 3) Redemption is the coincidence of the past and the future

And so it is that all love, including proletarian love, is based not on exchange, but redemption. Which is to say: The only authentic way to honour and redeem the gifts and sacrifices that others have performed for us throughout history is to sacrifice ourselves, to truly and purely give.

*

While those who mouth high talk

may think themselves high-minded,

justice keeps the book

on hypocrites and liars.—Heraclitus, Fragment 118

My general point is this: in that we are always-already bound by necessity, always-already the addressees of its calls, we already know how to love. There is already love in our lives; even amidst the socio-political malaise, we find moments of beauty that—because, and not in spite of, their precarity—make our lives worth living. This is not to say that we should be happy with our lot, but that if we can truly love our friends, partners and families, then we can truly love the People as well; we can truly practice proletarian love5. To do so however, we have to rise to the challenge of positing and recognising the existence of the People or Common Folk itself, as an abstract universality to which we are all necessarily bound. In an analogous way to how we presuppose an abstract equality between us and our friends in the very moment we claim that “they would have done the same for me”, we must dare to make that claim that is the basis for all solidarity: “it could have been me”. Even in relation to a struggle that seems as far away from us as possible, we must still dare to posit some abstract equality between us and those struggling; we must dare to invoke the People, or the Common Folk. At a smaller, more intimate level, we already do that in our love for our friends, partners, families, as I have demonstrated above. With the right perspective, we can scale this up to popular struggle too – as long as we have the faith to.

Of course, the odds are stacked against us; as the history of popular struggle tells us, the immediate result will usually be failure. From the 1381 Peasants’ Revolt to last year’s Black Lives Matter protests, the explicit demands of a movement (the abolition of serfdom; the defunding of the police) are basically never immediately listened to or implemented by leaders. But rather than the achievement of specific goals mouthed by party spokesmen, what actually matters is the ripples and traces that a movement leaves throughout history and culture, ripples that, sooner or later, we know will be redeemed because they speak to something undeniably true. (This is something we can already see happening with last year’s Black Lives Matter protests, which, despite having only limited “formal” successes, has undeniably enacted an irreversible phase shift in popular culture and consciousness.)

In sum, and to make a potentially heretical claim that I suspect will be misinterpreted: the aim is not, necessarily, to immediately succeed, but to redeem the struggles that have preceded us, and in the very same move, make possible the struggles of the future world to-come; to give struggle a future. Although we always hope for the success of leftist popular struggle, and vigorously seek to obtain it, the key point is that this is never the ultimate reason why we take part in political action. Instead, more often than not it is because it “feels important” to, in other words because we acknowledge some kind of historical duty to do so. We hear a call, a cry of necessity, and, in an act of proletarian love, we answer it. We fight in that call’s name as hard as we can. Whether we win or lose, that is what matters.

This historical, which is to say redemptive, perspective is crucial. Without it, I cannot see the Left doing anything other than going through the usual boom-and-bust cycles of intense heady optimism as a new struggle sparks into being, followed by the depressed, nihilistic crash as the movement is initially co-opted or quashed from above. Obviously, at some level, Realpolitik is necessary: building political coalitions involves compromises, tedious administrative labour, negotiations, long, frustrating meetings, organisation-building, strategy, and so on. Love is never enough; the idea that we could somehow practice proletarian love continually and consistently is naive, and we are not romantics. Nonetheless, it should be acknowledged that proletarian love is that wondrous thing that at base sustains and nourishes any political action. Proletarian love may not be the whole journey, but it is always the start (and end) point. The moment we lose sight of that is the moment we give in to cynicism, nihilism and hatred.

*

The class struggle, which is always present to a historian influenced by Marx, is a fight for the crude and material things without which no refined and spiritual things could exist. Nevertheless, it is not in the form of the spoils which fall to the victor that the latter make their present felt in the class struggle. They manifest themselves in this struggle as courage, humour, cunning, and fortitude. They have retroactive force and will constantly call into question every victory, past and present, of the rulers. As flowers turn toward the sun, by dint of a secret heliotropism the past strives to turn toward that sun which is rising in the sky of history. A historical materialist must be aware of this most inconspicuous of all transformations.

—Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History”

Hope need not mean expectancy. It suggests here rather the music which can come from the remaining chord.

—G. F. Watts on “Hope”

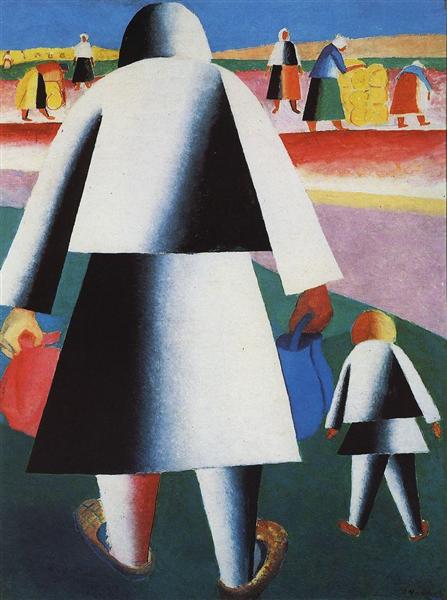

There is a curious feature in almost all of the faceless figures that populate the works of Malevich’s “Second Peasant Cycle”: none of them do anything. When Malevich painted peasants with faces, as he often did, they were always in the rapture of the work-to-be-done, walking through the fields, reaping the wheat, pushing a cart, and so on. But when the faces went, so did their activity: almost without exception, all of Malevich’s blank figures simply stand still and upright. Without eyes or faces, they cannot even be said to “face” the observer; they are simply downtrodden objects, indifferent to any gaze that may lie upon them.

This, of course, was all Malevich’s intention. Contra my over-romantic initial reaction to Peasants, it cannot be denied that Malevich’s work in this period is marked by a mood of utter destitution and despair. Amidst fields and with just enough signs of peasant-like clothing to make them recognisable as peasants, Malevich makes clear that his mannequins are not abstract geometrical shapes akin to a square or a circle, but figures that have lost something, had some violent act of dispossession performed on them.

And yet, one equally cannot ignore this fact: something remains. The brutal tides of history have robbed the peasants of their faces, but, still, there they are: patiently standing, patiently waiting. Consequently, while Malevich’s works here are clearly ones of utter despair, we must also recognise that it is precisely through this despair that they teach us quite a profound lesson about the true nature of those most sacred of things: faith, hope, and love. For even after the onslaught of modernisation, Malevich’s figures resist utter annihilation; they refuse to go away, their trace stubbornly remains there. Unable to be banished, they stalk the fields of history with all the other faceless others who have come and gone, waiting to be redeemed, waiting to become a face anew.

In their facelessness, genericity and equality, then, Malevich’s stalking figures are the People, the Common Folk. They are the aesthetic expression of all those faceless others we depend on and yet cannot name, as well as all those future beings to-come, waiting to be born. Viewed from the past, they are the ancestors we will never know, the anonymous workers who lurk behind every commodity, the bloodied masses who struggled for the freedoms that many (but tragically not all) of us enjoy. Viewed from the future, they are the generations to-come, the nameless publics to-be that will carry on our flame. But most importantly, viewed from the present, they are us. From the perspective of the sky of history we can see it clearly: behind all our faces is a faceless mannequin who acts as our hidden historical essence. The mannequin is a kind of depository that collects the traces of our life that will be passed on into the future, as well as enjoins us to all those historical conditions that made that life possible in the first place. It is, however, not guaranteed to exist. To be brought into being, the mannequin must be seen, and it must be loved. We must see it waiting, and dare to redeem it.

To be a “man of the People” or “among the Common Folk” — indeed, to practice proletarian love — far from involving an appeal to the lowest common denominator, instead involves a sober acknowledgment of our real, faceless, historical being. We are never just our face-possessing “selves”, but always-already the inheritor of a faceless community, tradition, or historical lineage that carries itself on, secretly, through us, into the future-to-come. The challenge now is for us to act like it.

-

In the same way, the circle, as a purely abstract mathematical object, is not found as such in Nature; we find many patterns and objects that tend towards perfect circularity (e.g. a soap bubble), but if we were to examine these closely enough, they would not of course be perfectly circular. This does not, however, stop the purely abstract concept of a circle being useful or meaningful to us; indeed, it is only by the a priori concept of the circle that we are able to intuit the natural circular object (e.g. soap bubble) at all. The same is true of any a priori (and thereby universal) concept of “the People” or “the Common Folk”. ↩

-

This is even the case with romantic love: we dare to make that anxiety-inducing first move and ask the other on a date, as if we had known them forever, even though we have only just met them and have no idea whether the date will be a disaster or not. In other words, we dare to act as if we are a Couple even though, in actuality, we are not yet; and it is only by this (again) leap of faith that the Couple can be built in the first place. ↩

-

A Lover’s Discourse, p.119 ↩

-

We often say of friendships, in approval, that they can be “picked up where they left off” or that “it is as if no time had passed at all”. These colloquialisms express the same point as here: that love, by necessity, involves a fundamental change in our experience of time. ↩

-

This argument is essentially the argument Simone Weil makes in her essay “Forms of the Implicit Love of God” (here), with the Christian/theological side largely subtracted. Here, Weil argues that, supposing one accepts God as a universal, necessary Being, then we all already have the love of God in us, but we are naturally born ignorant of it. As such, the love of God is practiced implicitly by us in other forms of relationship (love of one’s neighbour, friendship, love for Nature and art, etc), which, with reflection, we can then use as analogies or machines through which we can truly realise our love of God. I have spoken of “necessity” rather than “God”, but the underlying form or shape of these arguments (a particular love can be the basis of a universal one) is basically the same. (Weil’s Waiting For God, if you’re not too scarred by Catholicism, is genuinely excellent.) ↩