Posts on: modernism

Part I: Introduction

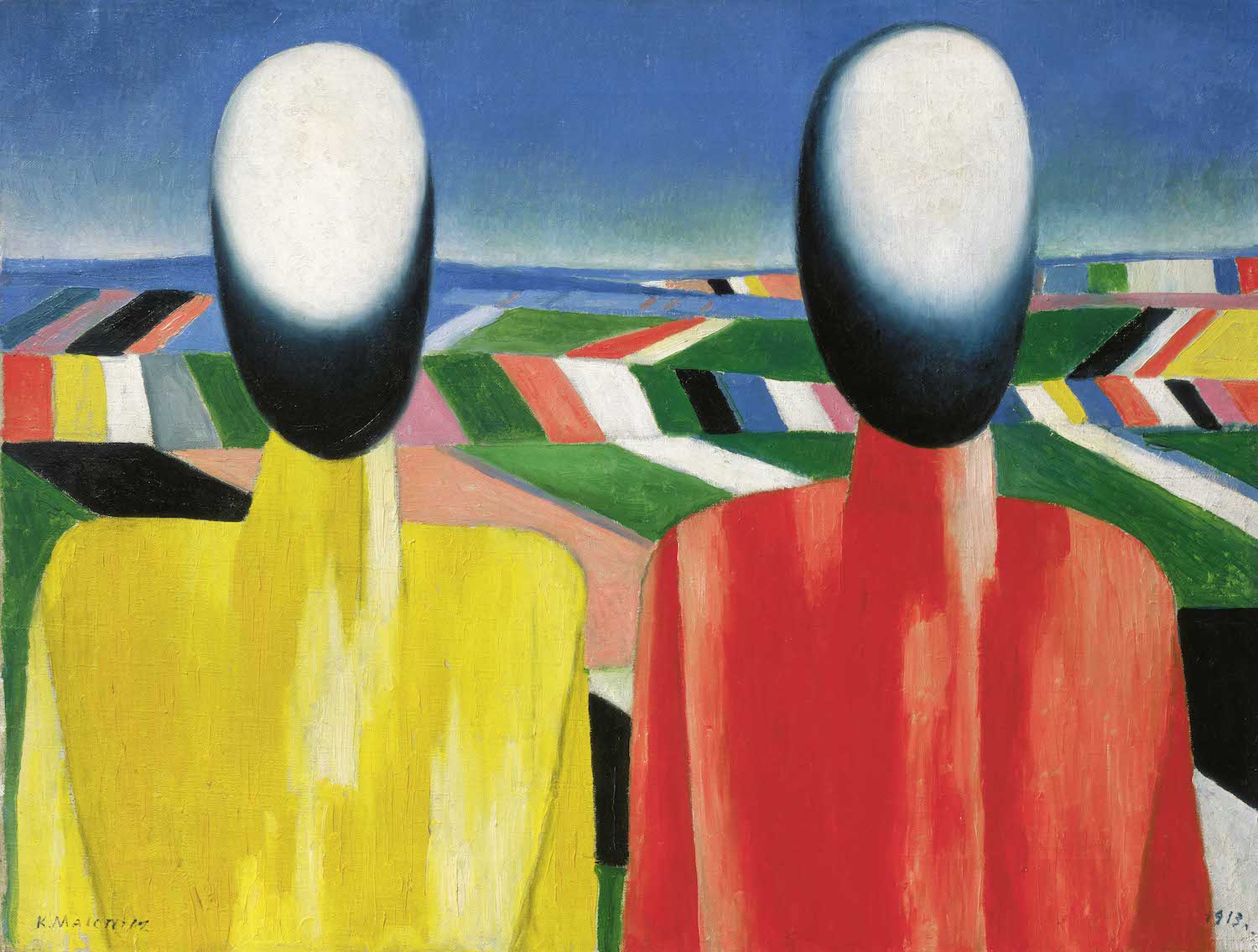

Before you learn anything about it, have a look at the artwork above. Sit with it for a while; feel it between your fingers. Notice the gradual, curving shadows of the figures’ spheroid heads; notice the way they stand beside one another; notice the stretching fields behind them.

When, in 1930, Kazimir Malevich painted Peasants, pictured above, it was intended as a solemn portrayal of the tragic consequences of the Soviet collectivisation programme that was then under way in the country. This process touched him in a personal way: Malevich had spent much of his childhood growing up—and working—on sugar-beet plantations in remote villages in Ukraine, and always felt a deep affinity with the peasant way of life. “I always envied the peasant boys who lived, it seemed to me, in complete freedom, amidst nature”, he writes wistfully in his autobiography1. “They tended horses, rode into the night, and shepherded large herds of pigs which they rode home at night, mounted on top and holding onto their ears.”

What stuck with Malevich the most, however, was the peasants’ natural predilection for art: a mixture of an artisan craftiness and a rich sense of folk mythology, symbolism, and iconography. As he writes:

The main thing that separated the factory workers and peasants for me was drawing. The former didn’t draw, didn’t know how to paint their houses, didn’t engage in what I’d now call art. All peasants did.

Later on he adds:

The village, as I said earlier, engaged in art (at the time, I hadn’t heard of such a word). Or rather, it’s more accurate to say that it made things that I liked very much. These things contained the whole mystery of my sympathies with the peasants. I watched with great excitement how the peasants made wall paintings, and would help them smear the floors of their huts with clay and make designs on the stove. The peasant women were excellent at drawing roosters, horses, and flowers. The paints were all prepared on the spot from various clays and dyes. I tried to transport this culture onto the stoves in my own house, but it didn’t work. I was told I was making a mess on the stove. In turn came fences, barn walls, and so forth.

Malevich knew this world was special because, ironically, he did not entirely belong to it: unlike the peasants, he identifies himself as living in a “second society” of “factory people”, owing to his father’s employment at the nearby sugar refinery, where he often worked night shifts. Whereas Malevich sees the peasants living a bucolic life of freedom, the factory people worked in something akin to a “fortress” in which they “worked day and night, obeying the merciless summons of the factory whistles”. “People stood in the factories, bound by time to some apparatus or machine: twelve hours in the steam, the stench of gas and filth.” Meanwhile, in the winter, as the factory people worked day and night:

…the peasants would weave marvelous materials, sew clothes; the girls would sew and embroider, sing songs, dance, and the boys would play fiddles. […] There was none of this with the factory people. I quite disliked that.

Raised amongst the peasants, then, Malevich saw clearer than most the miserable, mechanised (un)life that saps the urban working class; and so, when the Soviet collectivisation reforms came along, he could only apprehend them with horror. As individual farms were forced to collectivise and subjected to strict production rules and quotas, the previously rich cultural life and traditions of the various were assaulted and erased. Peasants were reduced to homogeneous cogs in the State’s machinery; they were, quite literally, faceless mannequins. Lives, as well as cultural traditions, were lost: the collectivisation reforms contributed to a famine that led to millions of peasants losing their lives. The Face of the Future Man, runs the title of one of Malevich’s paintings from this period: it is simply yet another blank, haggard head.

*

The back-story of Malevich’s Peasants, then, appears unequivocal: they are damning critiques of the undead Soviet machine, mournful elegies for a lost peasant way of life. But, alas, on this point I must make a confession: for quite some time now, I have seen in Peasants, and indeed all Malevich’s work from this period of his life, a quiet beauty. Until recently I had assumed that they were celebratory pieces produced in the early, heady times of the 1917 Revolution: muted, utopian expressions of the new Soviet man, stripped of all parochial identifications and hang-ups. Against bright, multicoloured fields, Malevich’s figures appear like modernist symbols of a fresh start, a new humanity, that looks forward into the future while still remaining close to their roots, quietly undertaking the essential work of tilling the soil, growing food, and feeding the people. Old yet new, cultured yet grounded, proletarian yet in power, Malevich’s mannequins gave me hope that all those wild, contradictory dreams that leftism seeks to realise were possible: because look, they’re there, on the canvas; we can see them. And if it can be captured in art – why not in practice?

And yet, as I was soon to find out, there had been a mix-up. Malevich intended exactly the opposite of the above: the peasants’ facelessness was not to be exalted as a “fresh start”, but mourned as the sign of the death of various rich cultural traditions. One wonders: how could I get it so “wrong”? How could this piece of art elicit two so completely opposed readings?

-

Malevich, “Chapters from an Artist’s Autobiography”, October journal, 1985, translated by Alan Upchurch. Available here. Citation here is from p.28. ↩

I may as well begin this roundup with a frank admission: at the beginning of this year, I did not know how to read.

Sure, I knew the technicalities: I was familiar enough with the particular socially agreed match-up of phonemes, graphemes and meanings that constitutes the English language. Familiar and capable enough, in fact, to practically inhale vast quantities of the written word. But we should be clear in asserting that such an ability to automatically respond to linguistic cues is not the same as reading, thinking, or intellectual practice in general. While it is such a practice’s necessary precondition, it is not the practice itself, which maintains its own singularity and uniqueness. For it is one thing to inhale, quite another to extract from that inhalation the oxygen that nourishes our intellectual bloodstream.

Things are changing, though. Last month, all too late in the year, I started a reading diary as a place to log my preliminary thoughts about the stuff I was reading, which were previously transiently flowing through me only to get lost in the aether. Principally, the diary is an attempt at commitment: a practice of staying faithful to and honouring the transformative impacts that books have on me, of – in Badiou’s terminology – showing fidelity to the Event (of reading). In our first readings of books, all we are left with is an accumulation of (positive or negative) sense-impressions or thoughts (“that bit was cool” “this bit was boring” etc), and maybe a few notes in the margins. Our duty after this first reading is to almost immediately begin a second reading, which drills into those particular sense-impressions and tries to clarify them, work out what in the book caused them to happen, at a level detached from (yet immanent to) the immediate experience of reading the book. This is what the practice of keeping a reading diary allows one to do: to give ourselves up to the books, to fully and psychedelically follow the path away from our “selves” that they set in motion.

Taking its cue from the reading diary, then, the principle of this roundup is precisely the opposite of showboating. Initially, the plan was simply to post a list of what I’d read this year, as some kind of achievement – but it quickly became apparent that this would be of no use to anyone, least of all me. A list such as that is like the initial material extracted from a mine, or the raw data collected by some online marketing platform: crude, incoherent, quite simply not ready. It is an uninviting mass that, far from being galvanised by some kind of connective or inspirational principle, simply lies there as sheer magnitude. A big, mangled rock of readings of philosophy, music criticism, literary modernism, SF and gothic horror, that no one wants to touch. (And even if, perversely, they wanted to, they wouldn’t know where to begin.)

When heaved and lugged onto the platforms of social media, those digital mirrors that provide the contemporary self with the reflected image that it mistakenly identifies itself with, this big mangled rock can only be self-serving and exhibitionist; a pseudo-intellectual form of dick-swinging. And lest it not be obvious, this is precisely what this blog stands against: the transmogrification of intellectual practice – quite simply, the practice of staying true to the Truth – into a putrid careerist ego-fiction. Intellectual practice cares little for what books are ostensibly “about”; it does not read blurbs. Instead it seeks to channel the real conceptual movements that weave through texts, extending and intensifying them into new, unknown zones. It operates in the underscore.

The below, then, has nothing to do with me. I can only predictably concur with k-punk when he wrote in 2004 that “writing, far from being about self-expression, emerges in spite of the subject.” And so it is with reading: when accumulated under the subjective frame of being “things I read”, the readings below can only appear as crude material, a mass of undifferentiated junk characterised only by its magnitude. But when the raw material is felt, held, and cradled, one begins to notice patterns; protruding excesses are transformed into murder mystery clues, ambivalent signs of something far stranger – and far beyond – any personal subject. (Adorno: “Every work of art is an uncommitted crime.”)1

What follows is therefore “my 2020 reading” as it deserves to be presented and acknowledged2. Not an individual ego-fiction, but various plateaus or planes of consistency, impersonal threads of connection. Not tightly policed “schools” of interiorised thought, but the open fields of the Outside. (Deleuze-Guattari: “A book itself is a little machine… [it] exists only through the outside and on the outside.”)3

Inherently defined by such an openness to the outside, such threads of commonality naturally bleed into and cross over each other – where does one field “end” and other “begin”? – and I will likely end up repeating myself. This is no problem, though: in fact it is precisely what allows us to see the works in their true form: flaming sites of multi-vehicle pile-up, the singular points of collision and intersection of the various planes of consistency that cut through them.

Or to put it more classically, we can say that this messy excess of cross-bleed is what allows us to stop seeing books as self-contained parts, and instead as particular instances of the Universal.

When one knows this, one knows how to read.

-

Theodor Adorno, Minima Moralia, part 72, “Second harvest”. ↩

-

Editorial notes: The below includes a mixture of books and shorter length pieces including articles, essays, interviews, blogposts, etc. A few things – some of them exceptional – have been left out, for one of two reasons: (1) because they did not seem to belong to any of the common threads that were at work in my reading this year (which is fine); and (2) because I either thought they were just not very good, or I still do not “get” them, or how to put them to use. ↩

-

A Thousand Plateaus, p.2. ↩