Posts on: friendship

Part III: Proletarian Love

Truth is not an unveiling which destroys the secret, but the revelation which does it justice.

—Walter Benjamin

At the risk of seeming ridiculous, let me say that the true revolutionary is guided by a great feeling of love. It is impossible to think of a genuine revolutionary lacking this quality.

—Che Guevara

If the entire problem of the Paradox was precisely that of fetishism, of romanticising things, then we can see immediately that this whole time, without realising it, we have been meditating on one central issue: love. If there is one thing that the Paradox demands of us, it is to practice a true and universal love; indeed, it is precisely this kind of love that proletarian politics aspires to.

As the Che quote above acknowledges, this does, initially, sound vapid, meaningless, and trite. However, in that any meaningful social revolution presupposes some kind of egalitarian fraternity of people who come together under the banner of a shared Cause, it is impossible to deny that the revolution implies revolutionary love, or at the very least some sort of revolutionary belonging. Let us call this revolutionary love “proletarian love”, and the subject that practices this love the proletarian or the comrade. In light of the discussions of the Paradox in the previous two parts, here we round off this essay by thinking through the following question: what is this proletarian love? Which perhaps is equivalent to asking that one vexed, eternal question: what is true love?

*

I don’t pretend to have any kind of definitive answer to this question, and I am not about to present a “Theory of True Proletarian Love” (which sounds like just about the least loving thing I could do right now). Nonetheless, I do think it’s possible to creep closer to some kind of answer by framing the question negatively, and asking instead: what is proletarian love not?

First off, proletarian love is not a love “for” the working class. This is simply the problem of fetishism all over again, the reduction of the working class to a particular series of fixed attributes and symbols. Instead, our aim is a kind of love which loves the working class insofar as they are stand-ins for all of humanity; in other words, a universal love. In Part II, we described this universality as concerned with a kind of “brush with the void”: the universal expressed itself through the working class via their encounter with the unnameable void at the heart of everything, for example when they attempted to start a community project solely through the resources they had available to them, and without any funding, recognition or validation from the State. Although the working class could be said to have a “privileged” relation to this void (also known as “epistemic privilege” by standpoint theorists and Mark Fisher), in principle anyone can—and indeed more often than not do at some point—have this kind of “brush with the void”. It is in regards to this encounter with the negative that our proletarian love is universal, as will be explored more shortly.

At the same time, however, it is important to clarify that this proletarian love is not universal in the sense that, say, hippies understand it, as a kind of uniform declaration of “peace and love”, or a chilled-out pacifism. This makes a mistake that we also identified in the previous part: the mistaking of universality for identity or uniformity. To practice universal love is not to show the same undifferentiated love to every particular thing we encounter. This, clearly, is not “love” in any meaningful sense: if you claim to equally love both the slave and the slave-trader who whips them, each of them accordingly know your love to be absolutely meaningless. It seems inescapable, then, but to argue that all love is inherently engaged in the activity of taking sides: love fixates on singular things and elevates them above the rest; it orders and prioritises.

And so we find ourselves at an impasse: our universal proletarian love must on the one hand a) aspire to universality, and yet on the other hand also be b) ruthlessly partisan; it must seek a grace and forgiveness that can extend to all, and serve the interests of the whole of humanity, and yet at the same time vehemently draw its dividing lines, say “no” to the bourgeois powers that be, and stand up against oppression and exploitation. So proletarian love in some way loves all humanity; but in another way, it detests the bourgeoisie, and it spits on the careerist demagogues that so frequently lead the people astray. Is this not a contradiction? How can one claim to love all humanity and yet basically hate one small, albeit powerful, section of it? Does this not defeat our entire project?

No, and for this reason: the particular and the universal are not separate “things”, categories or labels but rather, by necessity, dialectically related. In other words we reach the universal through the particular, and not in spite of it. Indeed any concept of “universal” without the corresponding concept of “particular” is quite literally empty, something akin to the hippie’s “universal love” referred to above.

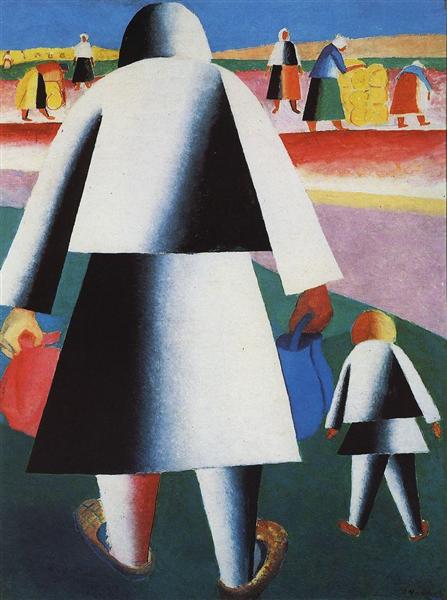

So to reiterate: proletarian love is something that strives to speak for (all) the People—in other words, the Common Folk—but does so through engaging in divisive, antagonistic political struggle. It is a kind of commitment to the Common Folk, the “true”, anonymous People lurking underneath the false images of the People that claim to be it (national flags, emblems, monarchs, and so on).

Let’s try and make this a bit more concrete; how would one feasibly practice proletarian love? How does one reach the universal “through” the particular? Our starting point is to remember that though we seek to act as (=on behalf of) the People, we never encounter people as the People, that anonymous, faceless public: we only ever interact with the particular people that we come across in our particular lives. So we begin with those often mundane, everyday moments that we are all so familiar with: a friend is complaining about their relationship, a colleague is moaning about their work, a family member is struggling to get the healthcare they need, and so on. Now, suppose we take the second example here: you are on your lunch break at work and your colleague, who you are quite friendly with, is having difficulties with their manager. Out of a fraternal love, you resolve to help them; after all, it could have been you with the difficulties, and in that situation the friend/colleague would have done the same for you. The colleague figures it’s just a small personal dispute, and they need your help preparing for a meeting with the manager in private, which you oblige to. However, after a little thought, it becomes clear that this situation could not just have affected you two, but almost the entire workplace, and indeed almost the entirety of the public, in principle. This changes things: it means helping your colleague prepare for a backroom meeting with their manager where they can privately resolve their differences no longer feels like a fair path to take. Instead, you and the colleague resolve to, rather than treat this issue as a private one between two individuals, open the issue up: to the other workers, to the public — in other words, to the Common Folk. You call a union meeting and get the workers talking to one another; you write up a press release about your actions and send it to the local newspaper. In short, you transform a private issue into a political issue; you turn a “for us” into a “for all”; you elevate fraternal love (the love between friends) into proletarian love (the anonymous love that exists between the People, as strangers, akin to “the love of one’s neighbour” in the Christian tradition).

It is this act of opening up that is the act of proletarian love par excellence, because it is precisely this that allows a particular struggle to connect with a whole host of others and begin to metonymically “stand in” for them all, and therefore begin to truly express the universal (= the People = the Common Folk). Had the friend kept their workplace complaint to themselves, this universality that the particular issue was “nested” within would never have been unravelled, and we would never had had the People chanting on the streets; we would never even believe such a thing possible.

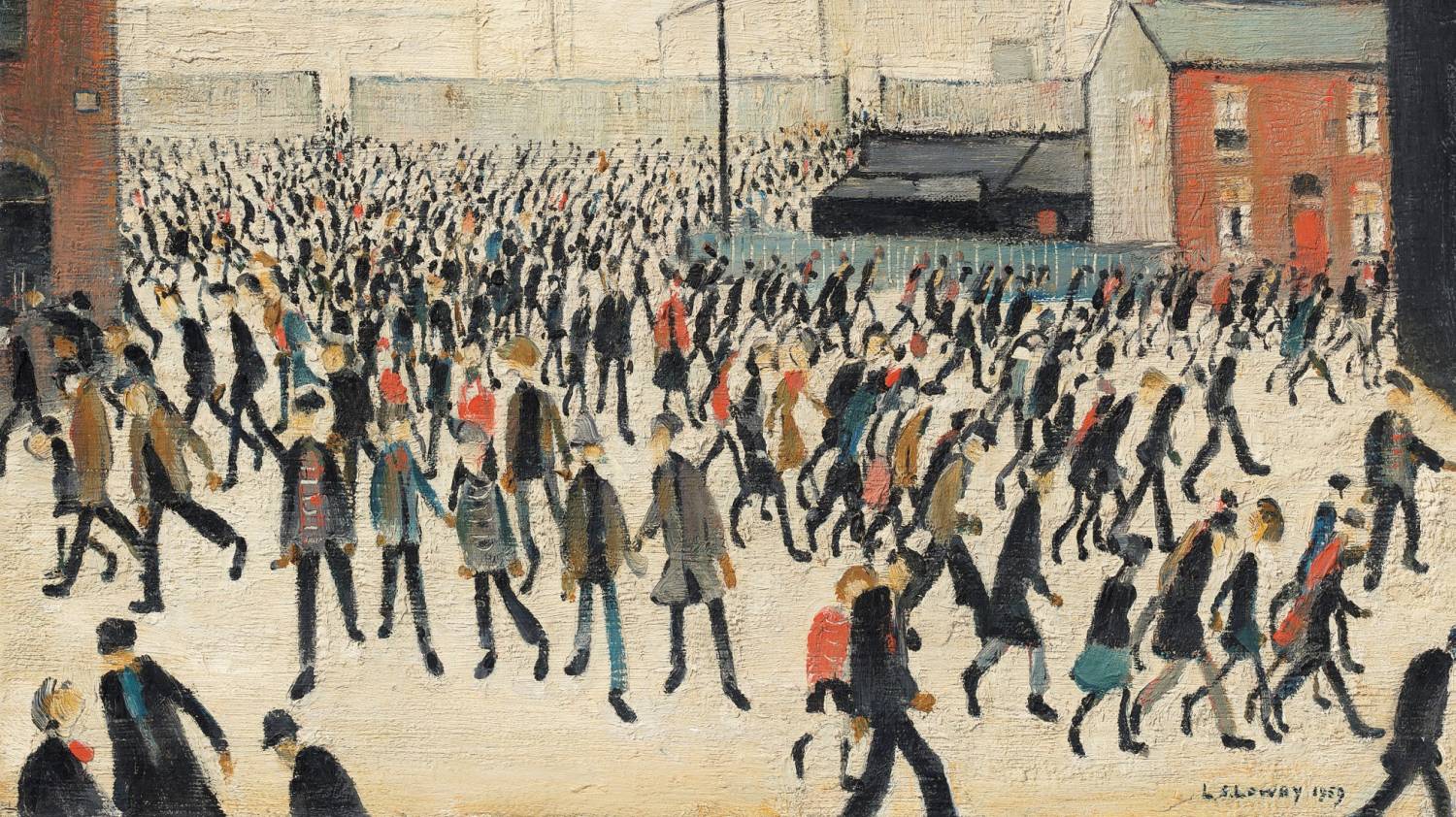

Now, this feeling (or lack thereof) of possibility is precisely why we characterise this entire process as “love”: because it involves faith, commitment. For as any activist knows, the People do not exist in actuality yet: they have to be built. (This is precisely what distinguishes the Left from the Right: the Right assumes the People always-already exist in an identifiable form.) The People, the Common Folk, are an abstract, ideal, a priori and (Zizek would say) “impossible-real” universality that has no actual existence right now, in that we do not live in a wonderful fraternity of equals who treat each other with total selflessness and kindness. This, however, does not stop the concept from being useful, and indeed necessary for political action1. It is, after all, literally impossible to think any kind of genuine politics without some kind of a priori notion of the People baked in from the start: all political struggle is grounded on the assumption that, at some level, the People genuinely are all equal, and all equally free, and that this a priori state has been corrupted by some injustice that has introduced inequality and hierarchy into the system. Of course, we know that this is basically a fiction, a mythology, but at the same time we cannot do without it: the alternative is to assume that instead of being fundamentally equal, humanity is fundamentally unequal, and this, naturally, simply ends up in strictly hierarchical, caste-like societies which could be said to lack any meaningful definition of “politics”, because everyone simply is forced to stay in their place rather than make claims on some shared resource. Instead of this arrangement, the proletarian dares to make that leap of faith that characterises all love2: they dare to act as if that a priori ideal—the People, the Common Folk—already exists, they dare to speak to, and as, the People, even though this subject does not exist yet, and is always, perennially, to-come. And finally, crucially, it is ironically only by acting as if this object really exists that we eventually actually make it exist. It is only by daring to believe that “the people will be free” that we eventually assemble the chanting mass on the streets that seems to genuinely sound the birth-pangs of a genuinely free People. The process here is always the same: the leap of faith retroactively constructs the ground it leaped from; the proposition back-engineers its own proof. (In CCRU-inspired theory circles, this process of fictions becoming real is known as “hyperstition”. In common parlance? “Fake it ‘til you make it”.)

-

In the same way, the circle, as a purely abstract mathematical object, is not found as such in Nature; we find many patterns and objects that tend towards perfect circularity (e.g. a soap bubble), but if we were to examine these closely enough, they would not of course be perfectly circular. This does not, however, stop the purely abstract concept of a circle being useful or meaningful to us; indeed, it is only by the a priori concept of the circle that we are able to intuit the natural circular object (e.g. soap bubble) at all. The same is true of any a priori (and thereby universal) concept of “the People” or “the Common Folk”. ↩

-

This is even the case with romantic love: we dare to make that anxiety-inducing first move and ask the other on a date, as if we had known them forever, even though we have only just met them and have no idea whether the date will be a disaster or not. In other words, we dare to act as if we are a Couple even though, in actuality, we are not yet; and it is only by this (again) leap of faith that the Couple can be built in the first place. ↩

People wearing ornaments and fancy clothes,

carrying weapons,

drinking a lot and eating a lot,

having a lot of things, a lot of money:

shameless thieves.

Surely their way

isn’t the way.

Reciting some passages from it in my reading diary, I realise a significant line of affinity that I share with the Tao Te Ching: an intense disdain for busy-bodies, pragmatists and the rich, and a profound sense of care for the most common and “unimportant” things.

This pleases me very much. We can complain about “common folk” being deceived fools, too stupid for their own good, but at least in all this they are honest, and not conceited. The common person goes about their life with no pretensions to doing—or being—anything else; they go to work unenthusiastically, cook meals for their children, care for their elderly parents, call up their friends, and go to sleep. In all of this, there is never any expectation of return, never any hope of recognition or reward, and a humble acceptance of the unremarkable everyday sacrifices that uphold our entire civilisation. There is something genuinely beautiful in this.

By contrast, careerist busy-bodies and networkers always act with at least some ingrained sense of superiority, some desire to sell themselves and their ego. This vanguard of the chattering middle and upper classes enter society with the misled impression that they have the power to control it. Having listened to their teachers, got good grades, and received their university degrees, and thereby dutifully obeyed the imperatives of the bourgeois order, they then make the crucial mistake of identifying this obedience with “their choice”. The chattering careerists, with an almost comic regularity, tragically project their egos onto the most impersonal of things: society, capital, and the labour market. They hold tight to the utterly futile dream, applying for graduate jobs which they will obviously never get while refusing to apply anywhere else, turning a blind eye to the poverty, squalor and exploitation that actually characterises their life, as well as the world around them.

Having reached this position in adulthood, those of the chattering classes either fully sign up to this undead careerist path, or they realise its error, leading to the widespread phenomenon of the middle-class “slacker” (of which one could arguably categorise myself), the person who has benefitted from the advantages of a middle-class upbringing and—ironically through these advantages—come to realise their empty promise. If the chattering classes are constantly riding a never-ending elevator always reaching for that Perfect Career (And Therefore Life!) which is always just out of reach, precisely because it is an illusion, the middle-class slacker leaps off the elevator to join the common folk on the shop floor below, to try and find a genuine exit from this hellhole with them. This is never easy, because the middle-class slacker is used to riding on elevators their whole life; being on plain, flat, horizontal ground is deeply disconcerting to them. Furthermore, they also discover the horrifying sight that the elevator had been powered by the grunts and groans of the immiserated common folk below this entire time—a fact they had always taken for granted. The slacker sees the emptiness on their faces, the marks on their skin, the beads of sweat on their hairline; and yet they also see a rowdy conviviality, a laughter, alongside simple gestures of selfless kindness. Despite being on uncomfortable and unfamiliar terrain, the slacker thus begins to feel their previous emptiness dissipate within them; their hearts open, and are filled with love.

This is why it is the common folk, rather than the prosperous chattering classes, who are the most religious in any society: for it is they who most viscerally feel the brute determinism of life, the sheer necessity of self-sacrifice. It is precisely this necessity of sacrifice that is never truly learnt by the chattering classes – instead they view society entirely through the lens of exchange: everything must have a return, an interest rate. Thrown into the conviviality of the common folk, the middle-class slacker is challenged to do away with all their ingrained habits of exchange, and instead learn to sacrifice: to learn what it means to truly give. When they learn that, they will realise they were one of that strange, borderless and impersonal collective of common folk the entire time; they will learn the beauty of the faceless and the generic.

* * *

So wise souls are good at caring for people,

never turning their back on anyone.

They’re good at looking after things,

never turning their back on anything.

There’s a light hidden here.

Good people teach people who aren’t good yet;

the less good are the makings of the good.

Anyone who doesn’t respect a teacher

or cherish a student

may be clever, but has gone astray.

There’s a deep mystery here.

Hence why I always have more time for common folk than the notable, smart and successful, even if I technically have more in common with the latter. Amidst the common folk there is never anything to prove – one just is who one is. The atmosphere is essentially egalitarian: the assumption is that whatever you do or say, you will still be one of us amidst the muck, still one of us struggling by, and so there is no need or desire to compete with one another. This doesn’t mean that every conversation is amazing and fulfilling, but that they are, at least, honest and genuine, and underlaid by a firm, shared ground of mutual trust and respect. This means that when an intellectual conversation does somehow get sparked, it can develop in an authentic and above all truthful way.

Face to face with some Bright Young Thing From Graduate School who’s clued up on philosophy, however, I freeze: because I know all too well how easy it is to get drawn into stupid dick-swinging contests – conversations whose content is purely the recitation of the “right” sources and names, in order to appear intelligent and, by virtue, superior. These conversations are never fulfilling because the primary concern of each participant is not the production of a shared goal, but simply not to appear like an idiot. Unsurprisingly, this is completely counter-productive to the task of raising collective consciousness. Anxious and untrusting of each other, the conversation degenerates into a charade, subordinated entirely to appearances and self-interest. Unable to open themselves up and loosen the tight security systems of the ego, the truth which is always latent and indiscernible in any situation/conversation is prevented from coming to light; instead what we get is the tedious and undead recitation of facts and soundbites pulled from elsewhere. (Faced with these situations, I usually find the best response is to stay silent, and quietly slink off with all the other bored observers of this dick-swinging contest to talk about something that actually matters.)

Reflecting on this, I offer the following conclusion: in order to get to the stage where intellectual discussion feels genuinely enthralling and productive, one must pass through the “common” or “base” stage first – one must be willing to expose and humiliate oneself in front of the other. In short, only when both are bathed in filth and excrement can two people, facing each other, have a worthwhile intellectual conversation.

This is essentially what I have with Nick and Alex: together us three have been through the highs and the lows, seen each other at our absolute worsts, and it is precisely these acts of mutual debasement and sacrifice—in other words, a true and eternal friendship—that allow us to intellectually converse in a way that feels true and genuine. All the heavy, stifling load of egotism and self-importance have been long dropped at the door, allowing the intellect to run free.

If you think being intelligent makes you a “superior” person, then, you are still clinging all too tightly to that object that you ultimately must renounce: the ego. The development of intelligence is not the simplistic movement up a hierarchy (this is an illusion fostered by academic qualifications), but rather a paradoxical—some would say divine—movement that is simultaneously an ascension and a descension. The person digging deep into the grounds of her trauma, for example, feels as if she has been struck by the light; she feels refreshed, anew, with a new clarity of understanding and purpose regarding her life. And yet, as she experiences such beatitude, she is surrounded by dirt and soil, the raw matter of the cosmos, all the traces of her pain and suffering, her traumatic memories, worse times. This, however, is not a contradiction – rather, it is precisely what makes her enlightenment true, genuine. To truly move up is to, simultaneously, move down.

It is this dialectic of high and low that helps explain why Mark Fisher was revered so widely: because unlike all the trendy social theorists who lurk the conference halls of academia, he was flagrantly open in his acts of self-debasement. In reviewing Girls Aloud singles and Terminator films, he was essentially destroying any hope of appearing a “serious”, “highbrow” or “important” critic, or in touch with any of the hip trends in academia, cultural criticism, and so on. But this was also what endeared us to him, for it was an essentially proletarian, or “common” sensibility – for if this is what he was listening to or watching, why pretend otherwise? Why not just start there? This hard-nosed prole sensibility – a kind of unsentimental “realism”, for wont of a better term – is often corrupted into a reverence for “common-sense” and the obvious, but in essence it need not be. It is not the demand to know one’s place, to stay stuck writhing in the dirt of the ground, but the knowledge that one can only stand tall thanks to the firm and dirty ground they compress beneath them. Indeed, understood correctly, it is neither a base anti-intellectualism, nor a cloying middle-class desperation to keep up appearances, but instead a plain-clothed commitment to the Truth. It is a commitment to start from where one brutally and totally is, warts and all: to genuinely see who and where they are, rather than, as the chattering classes are wont to do, turn a blind eye.

After all, the Now is all there is; each and every one of us is happening for both the first and last time.

Start there.

Read More »