16 Feb 2021

The Absent Centre of Community

The wager of this piece is as follows: it is incumbent on communists to think the commun- of their title, stemming from the Proto-Indo-European root *ḱóm (beside; near; with) and the Latin mūnus (a service; a duty or obligation; a favour; a spectacle; a gift), itself stemming from the Proto-Indo-European root *mey — “to (ex)change”.

We begin by acknowledging that the first goal of any radical leftist political practice is the activation, or raising to the level of self-consciousness, of common ties that had hitherto been obfuscated by force and in the interest of the oppressor1. Whether it be among workers, people of colour, migrants, prisoners, women, queer people, and so on, the initial aim is always to bring people together who the powerful wanted kept apart and compartmentalised. We seek the construction of that initial rowdy meeting, where workers who have never spoken to each other despite working in the same place start talking and making bonds, where women find out they are not alone in the face of belittlement and harassment by the men they encounter, and where migrants who have long felt almost hysterically dislocated from the society into which they have migrated find others who have felt the same impacts of xenophobic alienation. To go even further, we seek the meetings after the meeting, those initial friendly conversations between the meeting’s participants on the bus home, or outside sharing a cigarette, about anything in particular… Those first signs of a budding, the sprouting of something new, matched by the excitement and nervousness about what it could become.

What is the nature of these “common ties” – what does it mean to hold in common? We can begin to reach an answer here by noting how the common is different from the equivalent or identical. While the statement “A is identical to B” proposes that A=B, “A has X in common with B” does not propose that A equals B at all – simply that they are both somehow involved with the common third term X. To state the obvious, A and B can be drastically different in numerous ways, and still have something – X – in common. (This all appears obvious, but I state it to stress the fact that while we often think of communities as founded on a principle of identity or homogeneity, the opposite is true: communities are instead founded on a principle of difference, on that “something extra” that must exceed the common term X.)

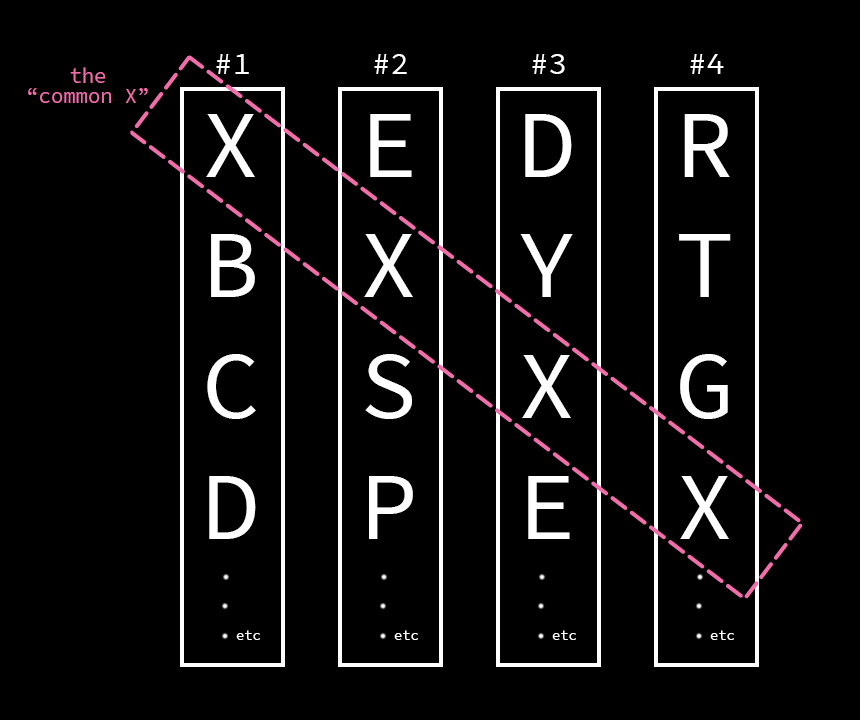

This leads us to that mysterious X – the commonly-held thing which we will hereafter term the common X. Now, this X is a strange entity: while it must possess some degree of repetition in order to hold the community together and give it some consistency, it is also something that necessarily exists in excess of any “singularity” (e.g. individual person, television programme, social media platform, whatever). The common X traverses all singularities – it cuts across and surpasses them, in order to “connect” them. Consider the diagram below2: here we have a “community” of four parts, #1-4, which all share some common characteristic, X. If we want to consider the common X in itself, rather than simply as a characteristic of some specific part, we are forced to cut across and traverse all the four parts, leading to the sketchy pink box in the diagram. This “box”, however, is quite unlike the others in the diagram, which depict specific parts with some kind of demarcating line between “inside” and “outside”. For the repeated Xs in the pink common box are not simply a collection of elements, as in a part-box; they are instead the repeated iterations of “one” consistent plateau – X – in different particulars. The common X therefore lacks any principle of interiority: to borrow a phrase from A Thousand Plateaus, the common X “exists only through the outside and on the outside”3 – interiority is alien to it. The X has a singularity and consistency, but no (self-)identity; and it is precisely this quality that allows it to hold together disparate parts, founding a community or commons.

At the “centre” of any community4, then, is this mysterious common X, this element held in common that the community in a way “hinges” around. Take, for example, the community around a particular school: that amalgamated multiplicity of friendships between pupils, after school clubs, relationships between parents, after work drinks between teachers, the conversations in the staff kitchen between cleaners on their break, weekend sports matches, school trips, and so on. Here, the common X may not appear mysterious at all – is it not simply the school, as a material “thing” made of bricks which teachers inside, etc? Yes and no: while a stable material structure is no doubt essential for a school – and thereby a school community – to exist and flourish, so long as we conceive of this structure as simply a “thing” in the commonly understood sense of the term (i.e. an “obvious” object of our consciousness that we can manipulate and control), we will never be able to explain what actually drives or constitutes the school community. For remember, the common X is not a “thing” in the usual sense of the word (i.e. an individual, obvious/transparent, controllable object), but something that traverses such individuated “things”, that cuts across and exceeds them. It is, to use the conceptual language of Gilbert Simondon, not an individual but transindividual5.

Lest this sound overly jargony, let us specify this example some more. Take two children: one is a bookworm and a teachers’ pet, and comes from a middle-class home; the other has had bouts of low attendance because of poor mental health and an unstable family life, and comes from a more working-class background. While the former thoroughly enjoys school and feels “at home” in class, going to clubs and bantering with the teachers, the latter finds the disciplinary environment of the school profoundly alienating, struggles to engage in class, and consequently thoroughly dislikes school. Both of these children are in the same school, potentially in the same class, even sat next to one another – and yet each has an experience of school that their classmate would find basically impossible to genuinely imagine or relate to. So on the one hand, we have “the school” presenting itself to us as a fun, rewarding environment; on the other we have “the school” as an alienating, harsh, and confusing institution. Bring in even more students into this example, and we could add “school as boring” to the mix, “school as racist”, “school as sexist”, “school as funny”, etc, etc – how is it that one “thing” can present itself to us with so many faces? The usual interpretation of such a problem is simply to argue that these are just different “opinions” held by the different students at the school – in this reading, the differences are “colonised” or “domesticated” by the individual subject; each different perspective on school becomes a property possessed by the individual, subordinating difference to identity. In other words, here we read the differences on the side of the individual subject(s), conceived as a separate, self-contained Wholeness. The more radical reading, however, is to posit that these internal gaps or fissures are on the side of the “school-in-common” itself – it is the school as the common X which is split, fractured, internally differentiated, and it is precisely this internal fracturing that enables it to be the basis or “centre” of the school community. When two students from the same school express different opinions about school, this tells us less about the “inner truth” of each student’s personality/individuality but rather, on the contrary, demonstrates the internal differentiation of the commonality “school” itself.

Consequently, the common X at the centre of our imagined school community is not simply “the school” as some simple object consisting of bricks and teachers, but instead what we have called the school-in-common, a strange entity that cuts across and exceeds all the singular elements that hold the school in common (students, teachers, parents, the bricks, the earth beneath it). As we have demonstrated, in order to cut across and connect singularities like it does, the school-in-common (or “common X”) cannot be a fixed, positive, transparent object: instead it is perpetually fracturing itself, emptying itself of any determinate content. The “generating principle” of any community, then, is never some Master or Leader who stands tall at the centre and proclaims to symbolise the community and speak for it “as a whole”, giving it some kind of fullness/presence. No – such a proclamation is always the retroactive attempt to paper over and fill in the self-emptying void of the common X that is the primary basis and “generating principle” for any community6. The common X incessantly splits itself, differs from itself, and it is through such self-differentiation that it becomes open to the outside, that it extends its commonality and builds/generates the community. In contrast to the figure of the Master-Leader who claims to symbolise and “be” it, the community is, then, instead always centred at its edges: it is the way a community “buds” at its fringes, self-differentiates, or changes itself that defines what it is. The community’s becoming is its being.

This is all, naturally, difficult to wrap one’s head around. Primarily, this because no one ever directly experiences the “school-in-common” in itself; the “common X” is not an object that is given at the level of our individual experience and (self-)consciousness. Why? Because it necessarily exceeds all individual experience. If it did not, we would not have a community, but rather a series of detached individual elements – the good and the bad student would be trapped inside their own personal prisons with nothing in common, least of all going to the same school. Thinking and understanding community therefore necessitates that we think in terms of difference, rather than identity – and part of such a thinking involves accepting that at the centre of any community is an absence, an incompleteness. For as soon as we identify a community with some positive object given in experience (“the centre of the school community is the school as a simple, obvious, material object”) we fail to understand the community as such, we “kill” it.7

(It is all somewhat like an asteroid orbiting the Earth; as anyone who has studied physics or mechanics knows, a thing in orbit is technically “falling” towards its gravitational centre point – in other words, the asteroid is technically falling towards Earth, compelled by the force of gravity. Due to the speed and angle of its departing flight path, however, it never reaches Earth. One can thus imagine us as aliens on an orbiting asteroid, constantly under the impression we are about to hit our gravitational centre, the mysterious X at the centre of our community – but always doomed to fail, for to hit the centre would be kill the orbit, or in our analogy, the community itself…)

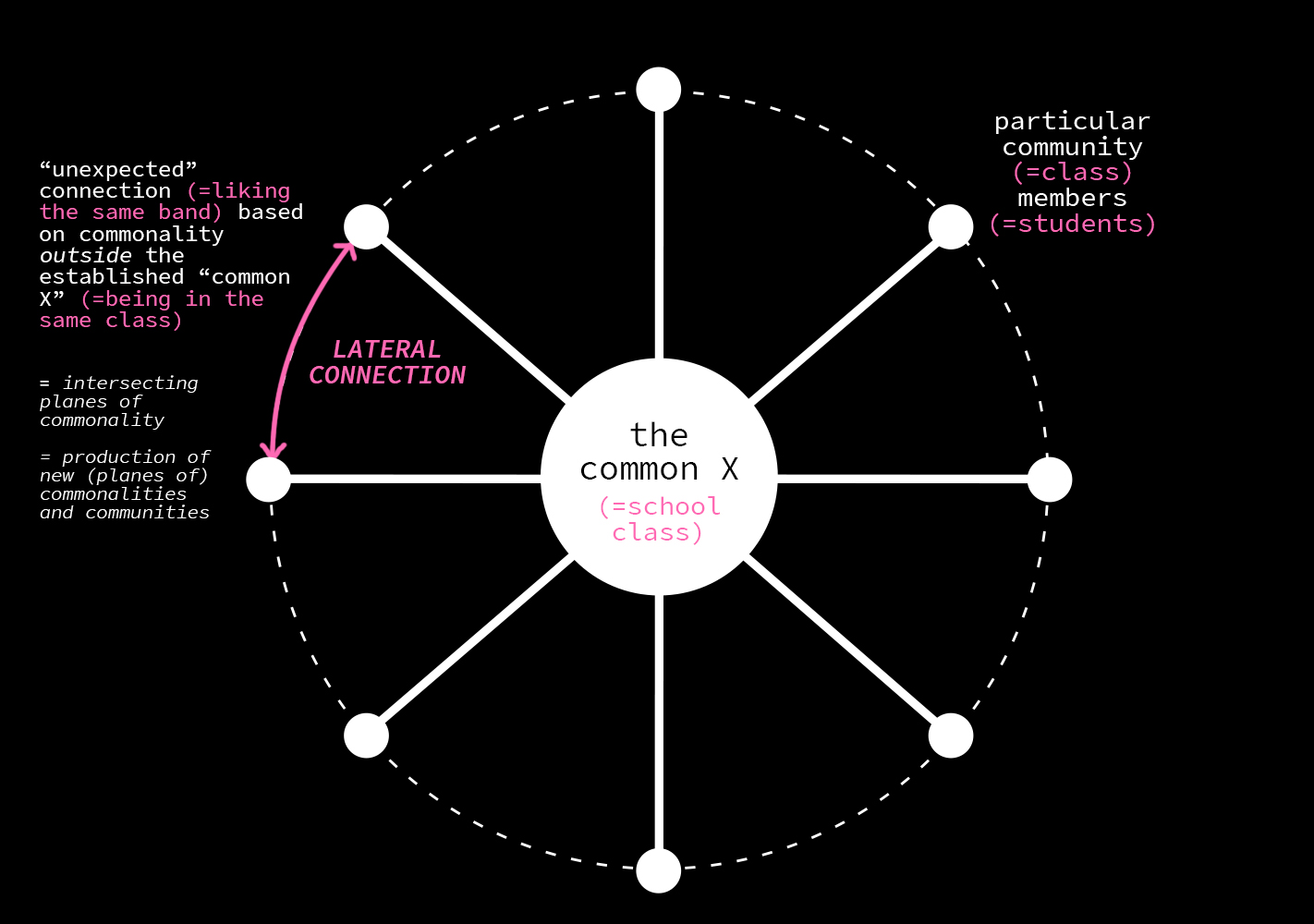

A strong and thriving community, therefore, is resolutely not one where everyone thinks the same, dresses the same, or in other words is subordinated into homogeneity through some transcendent Master-Leader. Quite the opposite, the strength of a community lies in its capability to “bud” and form new communities. To continue the school example: take two students in the same form who are both fans of the music of, say, SOPHIE8. During the breaks and gaps between and within lessons, they get talking and learn that they are both fans of the cyberpunk-pop artist’s music. As they bond over this common connection, they decide to form a band inspired by SOPHIE’s, and other musicians’, work. This band then starts playing gigs in the local area, which their classmates and other locals attend. They soon develop a small fan community who bond during the band’s gigs and talk about them online. All things considered, then, a thriving and budding communal scene is formed at the intersections of three communities (school – SOPHIE fans – the band).

What we have here, then – as the diagram above demonstrates – is one community “budding” into another, smaller, the enactment of a lateral connection between members of one community (the school) which enables the formation of a new community (the band). We say this as if the lateral connection comes “after” the (school) community that pre-exists it; as if first there was an “established” community, and only then did these unexpected “lateral connections” start happening. But this is misleading. The truth is closer to the opposite - lateral connections “are” what community “is”. Unlike the codified and hierarchical relationships of the Institution, the type of connection proper to the community or collective is always lateral, unexpected, open to the outside. Communities are lateral connections. The community (or common X) only becomes “itself” by, as we have noted above, an activity of self-differentiating through a collision with other commonalities outside “itself”. In our example above, the “school community” became thriving and active when it created a kind of “puncture” that was open to the outside (e.g. the gaps between lessons where students can talk freely outside the dictates of the lesson), thereby allowing it to “intersect” with the “SOPHIE fan community”. And this intersection was, precisely, the formation of another new community – the “band community” formed by the two students.

The takeaway is clear: communities as such are defined by their continual “bleeding into” other communities, but this “bleeding into” must not be understood as a kind of muddying or blurring, such that each of them is reduced to a homogenous mush. No – instead, the commonality or continuity between communities is always founded on, ironically, a discontinuity, a fractured disjuncture, a difference from the other communities.

* * *

We thus arrive at the following propositions:

#1: The Absent Centre. Every community is structured around, and given consistency by, a “common X” that lies at its centre that may initially appear obvious, but when approached must necessarily recede infinitely, and, despite their best attempts, can never be completely “colonised” or “domesticated” by some Master-Leader. For shorthand, we call this “common X” the absent centre of community: a centre that must continually empty itself, split itself, differ from itself, in order to cut across and connect its singular individuated elements.

#2: Psychedelic Lateral Connections. Consequently, we propose that the proper path of all revolutionary (political) practice is the continued pursual of lateral connections: the following – and construction – of unexpected or suppressed threads of commonality that, when pursued far enough, open out onto the Universal9. To borrow language from Badiou, we could phrase this as a fidelity to community’s absent centre: a principled commitment to channelling, through our practice, its continual self-emptying and self-differentiation. In other words, we assume the role of the absent centre; indeed, we seek to be an absent centre ourselves by seeking ways to make the various lines of commonality that run through us collide and intersect. (As in our example above, where the students took the commonalities of a) being in the same school and b) being fans of SOPHIE and spliced them together, in order to form a new community.) Today, the enemy of such a practice is always a craven careerism: a cowardly rejection of an immanent collision of planes for a homogenising subordination of all practice to the transcendent One of the Career Goal, of “future career prospects”.

It is for precisely these reasons that we organise ourselves as workers, women, migrants, renters, etc; not just to struggle for adequate “representation” or even better wages, but to – through this very struggle – psychedelically and irreversibly raise our consciousness. The collective organising is the goal, because (when done properly) the organising is psychedelic. For in that it is necessarily a collective activity (it involves people working together, discussing what they agree on and what they should demand, etc), the organising is precisely what allows a previously latent “common X” to move from simply being in-itself to being for-itself, which, as we have seen, involves the emergence of a constant process of self-emptying and self-differentiation: following a common thread far enough necessarily involves us colliding with and following other, different, threads of commonality and connection, on and on and on… In this sense, organising is always something that sets individuals on a path away from themselves, such that, months or years later, they look back bewildered and say to themselves: “how did I get here?” It is a look, furthermore, tinged with misrecognition: the organiser looks back at themselves at the beginning of the process and sees a different person, a person they are glad they no longer are (“that was me?”)10. Collective organising reveals the individual ego or sense of self to be a contingent artificial construction, and by, the same move, capital’s apparatuses of discipline and control. The world is cracked open.

And lest this sound like woolly hippy shit, consider the words of one former Lucas Aerospace worker and union activist who was heavily involved in the drafting of the Lucas Plan, a rank-and-file attempt in the 1970s to repurpose the state-owned aerospace firm away from military goods towards “socially useful technology”:

We were learning as we went along. And not only developing a Corporate Plan, but in many respects developing selves… because the Corporate Plan, as it develops, it changes you! We think about that, we’re feeling our way and making mistakes and all the rest of it, and as we progress, because we’re doing what we’re doing, we’re then looking at ourselves, and [we realise that] you’re not the same person at the end of the exercise as you were at the beginning! You’re really not! You just change… You see how things are interrelated… Capitalism puts you into isolation: you’re isolated there, you’re isolated there… you never look at the whole.11

Or, the only way for the working class to become for-itself is, ironically, to abolish itself. Marxism as disidentity politics.

#3: Community = Joy. The extension or realisation of any community is therefore founded on a principle of action, understood in the Spinozist sense. In the Ethics Spinoza distinguishes between passions and actions: passions are affects or modifications of our body prompted by an external cause of which we are ignorant, thereby leaving us passively beholden to it; actions, meanwhile, are affects or modifications of our body of which we ourselves are the cause, and which we consequently have a “true” or “adequate” idea/conception of. We propose that community cannot be built through passions, or passivity: in our school class example, for instance, this would simply lead to the students passively remaining in their roles “as students” directed by (and defined in relation to) an exterior teacher, thereby removing any opportunity for unexpected lateral connections that would extend/build the community (e.g. by starting a band). In contrast to such a picture, we assert that lateral connections are always active: we cannot rely on anyone else to enact them but us, ourselves. To take up the mantle of lateral connections is to affirm ourselves as singular, unique bundles of intersecting commonalities, rather than define ourselves solely in relation to some external cause or Master to whom we are separate12. And as Spinoza makes clear throughout the Ethics it is this kind of activity – understood in opposition to passivity – that is truly joyous. For in that it is only us who can make the lateral connection, such an activity necessarily increases our power of action – which is precisely the Spinozist definition of joy (see Ethics, IIIP11).

From this we deduce the following series of equations: Community = Lateral Connections = Joy. Or more simply, Community = Joy.

-

This was originally a fragment from what was to be a multi-part series of posts on social media that I had been very gradually and haphazardly adding to since last May, and intended to publish here early this year. Other projects have come up, though, and as a whole the series feels already like something that I have moved beyond, so I have decided to drop it. This fragment, however, I still like, and think stands on its own two feet. Again, I have already “moved beyond” certain bits of it, but a lot of it still works, and it’s good to have some kind of testament to the months of work that ultimately led up to it. ↩

-

Like all the diagrams in this piece, this is ridiculously speculative. The diagrams presented here are simply little drawings I have made to set some thoughts into motion, and while they undoubtedly claim some productive and clear relationship to “the Truth”, they equally do not claim to accurately “be” or “represent” it either. (This is a bad approach to diagrams in general, anyway.) The “rigorous” logician or mathematician would no doubt balk at this approach; in particular I can imagine a set theorist picking apart and redrawing this diagram quite ferociously, reconceiving the boxed parts here as round sets, which all intersect Venn diagram-style over the shared element X. This intersection – which in mathematical notation would take the form #1 ∩ #2 ∩ #3 ∩ #4 – could then be described as its own particular set of its own, ridding the “common X” of all its “strange features” I discuss here. I can’t claim to have the knowledge to counter this, but I do have a sense that the set theory approach freezes and fixes the necessarily dynamic movement in commonality, thereby ironically misrepresenting it. However you feel about that explanation, Badiou’s Being and Event is in the post as we speak, which leans on set theory quite a lot, so this isn’t the end of this line of thought… ↩

-

ATP 2013, p.2 ↩

-

In his seminars on postcapitalist desire, Mark Fisher states how he dislikes the term “community” because it suggests an “in” and an “out” of the community. I share Fisher’s weariness about the term, but note that his uneasiness comes from a reaction to a communitarian or nationalist appropriation of the term “community” that, as the theorising in this post is explicitly shows, is in fact a botched notion of community that subordinates it to some racialised Master-Leader. The right may be the ones speaking the language of “community”, but we should be open in exposing this as a wolf in sheep’s clothing, and assert instead that a correct theorisation of community, or collectivity, is indispensable to the Left. (As an aside, it is worth noting that Fisher was perfectly comfortable with and supportive of the notion of “collectives”, stating in a 2004 blog post that “there is no more urgent task on this hell planet than the production of rational collectivities”, for example. If one is uneasy about the use of “community” in this post, then, you can simply swap out the word “community” for “collective” and rest easy in the knowledge that you have “got it”.) ↩

-

For a short but rigorous introduction to Simondon’s works, see Muriel Combes’ Gilbert Simondon and the Philosophy of the Transindividual. ↩

-

And such a “filling in” often has disastrous consequences: as Zizek notes in both The Sublime Object of Ideology and The Ticklish Subject, it is this attempt to fill in and “gentrify” the emptiness at the centre of any community that defines totalitarianism as such. The problem with Stalinism, for instance, is that the Party/Leader claims to stand in for, or coincide with, the People in toto without any leftover, meaning that any slight deviation from the Party’s/Leader’s rules – as inevitably happens, such is the nature of community sketched above – is construed as a deviation against the People, and therefore in need of violent repression. The truth of the matter is, though, that this act of deviation, far from being an act against the People, is what constitutes the People as such. ↩

-

To put a Kantian twist on it, we might say that community or commonality is the necessary precondition of individual experience as such; there is no singular individual without a community or field of commonalities that precedes them. ↩

-

Ominously, I wrote this only a month or two before SOPHIE’s tragic death earlier this month. May she live on as an immortal icon. ↩

-

The argument here is inspired by Reza Negarestani’s excellent essay “On the Revolutionary Earth” available here, which I also discussed extensively in my post on Scottish geotrauma. ↩

-

Mark Fisher: “Marxism is “better described as a disidentity politics. This is not to suggest that Marxism entails the empirical destruction of identities and ethnicities. It is to say that for Marxism, collectivity is organized on the basis of an indifference to difference.” (“The Proletarian Cogito”) ↩

-

As stated in the excellent 2018 documentary on the Lucas Plan, The Plan That Came From The Bottom Up. (Specifically Part 2, 22 minutes in.) ↩

-

In the school example, this would involve defining ourselves solely as “students” who do well in class and do their homework, etc, and refuse to form any relation with people outside the frame of “being a student”, an identity which is ultimately foisted upon them from the outside by teachers and the education system in general. ↩