27 Jun 2021

Loving Folk (Part I)

Part I: Introduction

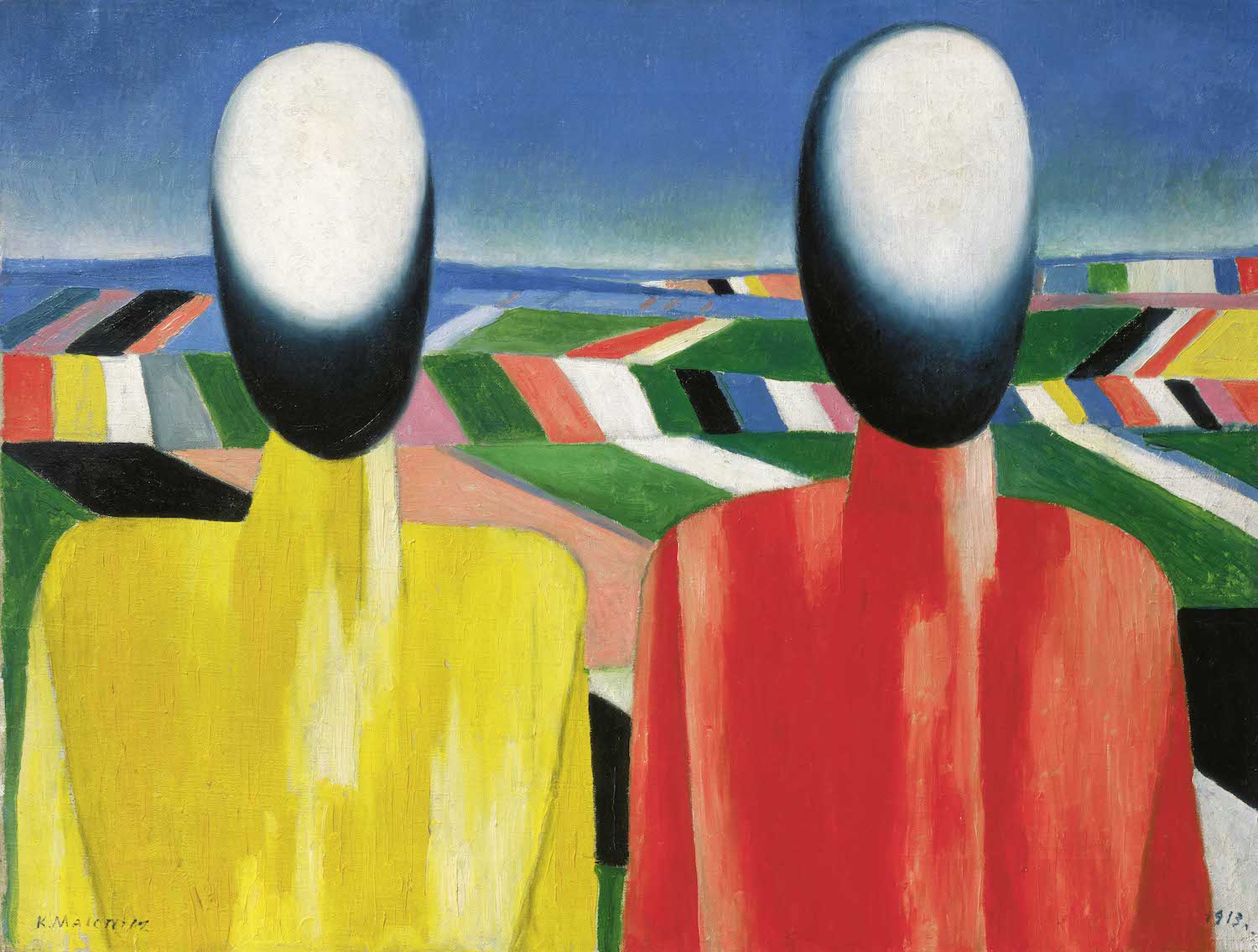

Before you learn anything about it, have a look at the artwork above. Sit with it for a while; feel it between your fingers. Notice the gradual, curving shadows of the figures’ spheroid heads; notice the way they stand beside one another; notice the stretching fields behind them.

When, in 1930, Kazimir Malevich painted Peasants, pictured above, it was intended as a solemn portrayal of the tragic consequences of the Soviet collectivisation programme that was then under way in the country. This process touched him in a personal way: Malevich had spent much of his childhood growing up—and working—on sugar-beet plantations in remote villages in Ukraine, and always felt a deep affinity with the peasant way of life. “I always envied the peasant boys who lived, it seemed to me, in complete freedom, amidst nature”, he writes wistfully in his autobiography1. “They tended horses, rode into the night, and shepherded large herds of pigs which they rode home at night, mounted on top and holding onto their ears.”

What stuck with Malevich the most, however, was the peasants’ natural predilection for art: a mixture of an artisan craftiness and a rich sense of folk mythology, symbolism, and iconography. As he writes:

The main thing that separated the factory workers and peasants for me was drawing. The former didn’t draw, didn’t know how to paint their houses, didn’t engage in what I’d now call art. All peasants did.

Later on he adds:

The village, as I said earlier, engaged in art (at the time, I hadn’t heard of such a word). Or rather, it’s more accurate to say that it made things that I liked very much. These things contained the whole mystery of my sympathies with the peasants. I watched with great excitement how the peasants made wall paintings, and would help them smear the floors of their huts with clay and make designs on the stove. The peasant women were excellent at drawing roosters, horses, and flowers. The paints were all prepared on the spot from various clays and dyes. I tried to transport this culture onto the stoves in my own house, but it didn’t work. I was told I was making a mess on the stove. In turn came fences, barn walls, and so forth.

Malevich knew this world was special because, ironically, he did not entirely belong to it: unlike the peasants, he identifies himself as living in a “second society” of “factory people”, owing to his father’s employment at the nearby sugar refinery, where he often worked night shifts. Whereas Malevich sees the peasants living a bucolic life of freedom, the factory people worked in something akin to a “fortress” in which they “worked day and night, obeying the merciless summons of the factory whistles”. “People stood in the factories, bound by time to some apparatus or machine: twelve hours in the steam, the stench of gas and filth.” Meanwhile, in the winter, as the factory people worked day and night:

…the peasants would weave marvelous materials, sew clothes; the girls would sew and embroider, sing songs, dance, and the boys would play fiddles. […] There was none of this with the factory people. I quite disliked that.

Raised amongst the peasants, then, Malevich saw clearer than most the miserable, mechanised (un)life that saps the urban working class; and so, when the Soviet collectivisation reforms came along, he could only apprehend them with horror. As individual farms were forced to collectivise and subjected to strict production rules and quotas, the previously rich cultural life and traditions of the various were assaulted and erased. Peasants were reduced to homogeneous cogs in the State’s machinery; they were, quite literally, faceless mannequins. Lives, as well as cultural traditions, were lost: the collectivisation reforms contributed to a famine that led to millions of peasants losing their lives. The Face of the Future Man, runs the title of one of Malevich’s paintings from this period: it is simply yet another blank, haggard head.

*

The back-story of Malevich’s Peasants, then, appears unequivocal: they are damning critiques of the undead Soviet machine, mournful elegies for a lost peasant way of life. But, alas, on this point I must make a confession: for quite some time now, I have seen in Peasants, and indeed all Malevich’s work from this period of his life, a quiet beauty. Until recently I had assumed that they were celebratory pieces produced in the early, heady times of the 1917 Revolution: muted, utopian expressions of the new Soviet man, stripped of all parochial identifications and hang-ups. Against bright, multicoloured fields, Malevich’s figures appear like modernist symbols of a fresh start, a new humanity, that looks forward into the future while still remaining close to their roots, quietly undertaking the essential work of tilling the soil, growing food, and feeding the people. Old yet new, cultured yet grounded, proletarian yet in power, Malevich’s mannequins gave me hope that all those wild, contradictory dreams that leftism seeks to realise were possible: because look, they’re there, on the canvas; we can see them. And if it can be captured in art – why not in practice?

And yet, as I was soon to find out, there had been a mix-up. Malevich intended exactly the opposite of the above: the peasants’ facelessness was not to be exalted as a “fresh start”, but mourned as the sign of the death of various rich cultural traditions. One wonders: how could I get it so “wrong”? How could this piece of art elicit two so completely opposed readings?

*

Peasants is just one example of a paradox which I think haunts all leftism, and that all leftists cannot help but confront at some point in their practice. The paradox ultimately boils down to this: every time we try and express what the working class “is”, we inevitably only end up expressing what it is not. Any attempt to speak of “working-class life” inevitably ends up doing an injustice to it, or not really talking about it at all. In fact, every time we try and pin down an “essence” of the working class, we fail. Something always seems to slip through the linguistic net.2

In other words, the problem is: can the working class speak for, or of, “itself”? Which is equivalent to asking: can the working class, itself, act? For these reasons, I call this paradox the Paradox of the Proletarian, hereafter “the Paradox”.3

Let me explain this a bit more. Say, that out of the fuzzy multitude of all those masses of poor, suffering, and exploited people, all their brute realities and experiences, good and bad, we decide to draw out a singular name: “working class”. Then, we try and apply that name to those brute realities – we say “this is working-class life”. So we could say “paying rent is working-class”, “not earning much money is working-class” or even “going to McDonalds is working-class”. Doing this, though, always feels wrong; uncomfortable – as if we are committing some kind of crime. The issue is not really the factual content of these statements (most working-class people do rent rather than own their own homes, for instance), but what they imply. For they seem to suggest that the people who find themselves labelled “working class” pay rent or lack money as some kind of essential property of their being, and are doomed to be stuck in this state for eternity, without any agency of their own.

Indeed, every time we try and explicitly slot the “working class” into language, one of two things always seems to happen:

-

1) Romanticisation: In singling out and naming things that seem to characterise working-class existence in a so-called “positive” way (e.g. going the the pub, getting a takeaway), in other words in trying to identify things that we can say definitively are “working-class”, we inadvertently reduce this existence to these single things. For as soon as we name these things, the real multiplicity of the working class takes over: of course not all working-class people go to the pub, especially those from cultural and religious backgrounds which do not condone alcohol, for example. Having done such a thing, then, we realise we have done a huge disservice to the sheer heterogeneity of the working class, a name that with much fragility holds together the lives of masses upon masses of people from all walks of life, with different languages, belief systems, and so on. In attempting to identify the working class as a whole, we have really only ended up talking about a very particular group of people which it is probably best to identify and name with a label other than “working class”, and then, through an act of romanticisation, assumed that this particular group characterises the entirety of working-class life. This is obviously false, and we find ourselves in a state of embarrassment: we have really spoken more about ourselves than the working class, which, again, has slipped through our linguistic net.

-

2) Denigration: In talking about the various lacks that characterise working-class existence—lack of money, free time, security, ownership, means of self-expression—we turn the working class into victims without any agency. The working-class are just the dark, murky shadows and leftovers of the ferocious ravaging of capital, the “real” agent of society; for after all, “money talks”. In other words, in attempting to talk about the working class, we have in fact ended up talking about capital/the bourgeois/etc. Once again, the working class have slipped through our net.

This, quite literally, is the Paradox in action, and it is exactly what we saw when discussing Peasants. On the one hand, we had Malevich’s decrying of faceless victimhood; on the other, my perhaps overly romantic reading. To give another example, it is also precisely what happens to any left-wing activist the second they really get involved in the nitty-gritty of political organising. In one way, the activist valorises the working class, knowing that there can be no meaningful revolution without them. Desperately seeking that concentrated moment of joy and consciousness-raising that accompanies any successful demonstration, strike or direct action, the activist diligently knocks on doors and hands out leaflets in order to get people to come to meetings, with a tired, but patient, optimism. But in another way, the activist curses—indeed, loathes—the working class for their “false consciousness”, their inability to see what’s good for them and act in their best interests. Most activists bounce frantically between the two poles of this love/hate relationship until they become dizzy, burnt-out and cynical; ultimately, they decide to resign themselves back to their own lives, unable to take the constant to-ing and fro-ing of the Paradox any longer.

These two attitudes are not contradictory: they need and imply one another, like two sides of the same coin. One seems to effortlessly slide into the other; it is akin to a finger trap, where the harder one pulls, the tighter the trap gets. A pull becomes a push, a push becomes a pull, and all the while, our swollen finger remains trapped.

*

There is one final example where we can see the Paradox in action, and it is, in fact, my own writing.

“Common Folk” was a rather hasty, and personal, attempt to find some way out of this deadlock by conjuring a kind of hard-nosed proletarian “spirit” that—as is demonstrated throughout this essay—is not easily put into words. This is why I spoke of “chattering classes” and the “common folk” rather than “middle class” and “working class”: the latter come too loaded with meaning, sticking all too tightly to the objects they’re attached to, when really what I was trying to capture was something much more diffuse and delicate, a kind of unspoken style, attitude or sensibility that, while ultimately being grounded in class divisions, can wander off from them and percolate of its own accord. (As I said in the post, there exists a certain way in which every single one of us is of the “common folk”, even if we do not know how yet, and this is what makes it beautiful.) Trying to capture this is difficult, however, and even despite all these attempts at care and delicacy, “Common Folk” still got caught up in the knot of language that the Paradox institutes. Its tone was continually bouncing between sounding romantic (“their hearts open, and are filled with love”) and patronising or denigratory (the very label “common folk” being the most succinct example of this). Of course, none of this was intended, and there were numerous points in that post where I was signalling that I was both aware of and trying to move beyond this paradoxical trap, but I wouldn’t blame anyone who read that and felt a bit suspicious about what I was saying.

But this is no mea culpa. I stand by everything I wrote in “Common Folk”, and the ideas it was trying to articulate. It was a condensation point, a dramatisation, rather than a detailed philosophical exegesis; that is the style it committed to. In the wake of its paradoxical entanglings, however, perhaps what is demanded now is precisely such an exegesis: a long and patient exercise in thought to clear the grounds in front of us, to show us the way out. Is there a way out of the Paradox of the Proletarian? Where does it come from? And in the light of this, what are the implications for praxis? It is precisely these questions that this essay meditates on.

Part II will be posted tomorrow

-

Malevich, “Chapters from an Artist’s Autobiography”, October journal, 1985, translated by Alan Upchurch. Available here. Citation here is from p.28. ↩

-

This is not the first time I have tackled these questions. For more musings on this question, see “Leaden Light of the Proletariat”. ↩

-

Mark Fisher knew this paradox as the “impossibility of working class achievement”. He writes of The Fall’s Mark E. Smith in the seminal “Memorex For the Krakens”: “Perhaps all his writing was, from the start, an attempt to find a way out of that paradox which all working class aspirants face - the impossibility of working class achievement. Stay where you are, speak the language of your fathers, and you remain nothing; move up, learn to speak in the master language, and you have become a something, but only by erasing your origins - isn’t the achievement precisely that erasure? (‘You can string a sentence together, how can you possibly be working class, my dear?’)” ↩